When I tell people I am writing a book that describes all of the plants that grow in Manitoba, they are often incredulous. “Don’t we already know how many plants species there are in Manitoba” they ask. Sadly, the answer is no.

To this day, botanists are still finding plants that they did not know grew in Manitoba, like White Avens (Geum canadense).

© Manitoba Museum

New to Science

Believe it or not, botanists documented and collected two flowers that were not believed to grow in the province, for the first time ever in 2021. White Avens (Geum canadense) and Tawny Cottongrass (Eriophorum virgatum) grow in northern Minnesota and western Ontario. However, they had never been scientifically collected in Manitoba before. These species join 268 other species of vascular plants that have been scientifically collected since the publication of the “Flora of Manitoba” book in 1957.

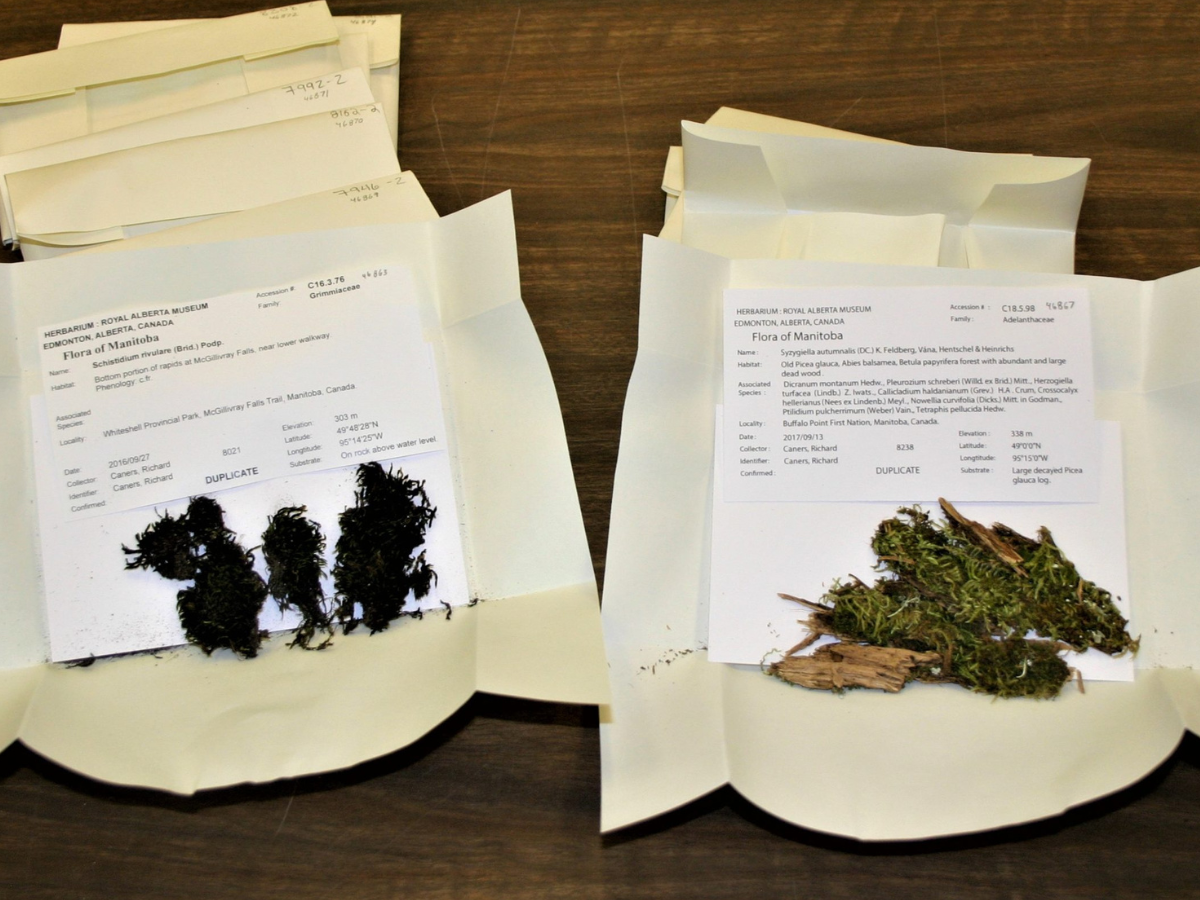

Further, the Royal Alberta Museum’s moss specialist, Dr. Richard Caners, also recently collected 34 species of moss that had not yet been officially documented in Manitoba. So, on average, nearly five new plant species have been added to our provincial list of flora each year for the last 65 years.

This recently acquired collection of mosses, contains specimens of several species that scientists did not know grew in Manitoba.

© Manitoba Museum

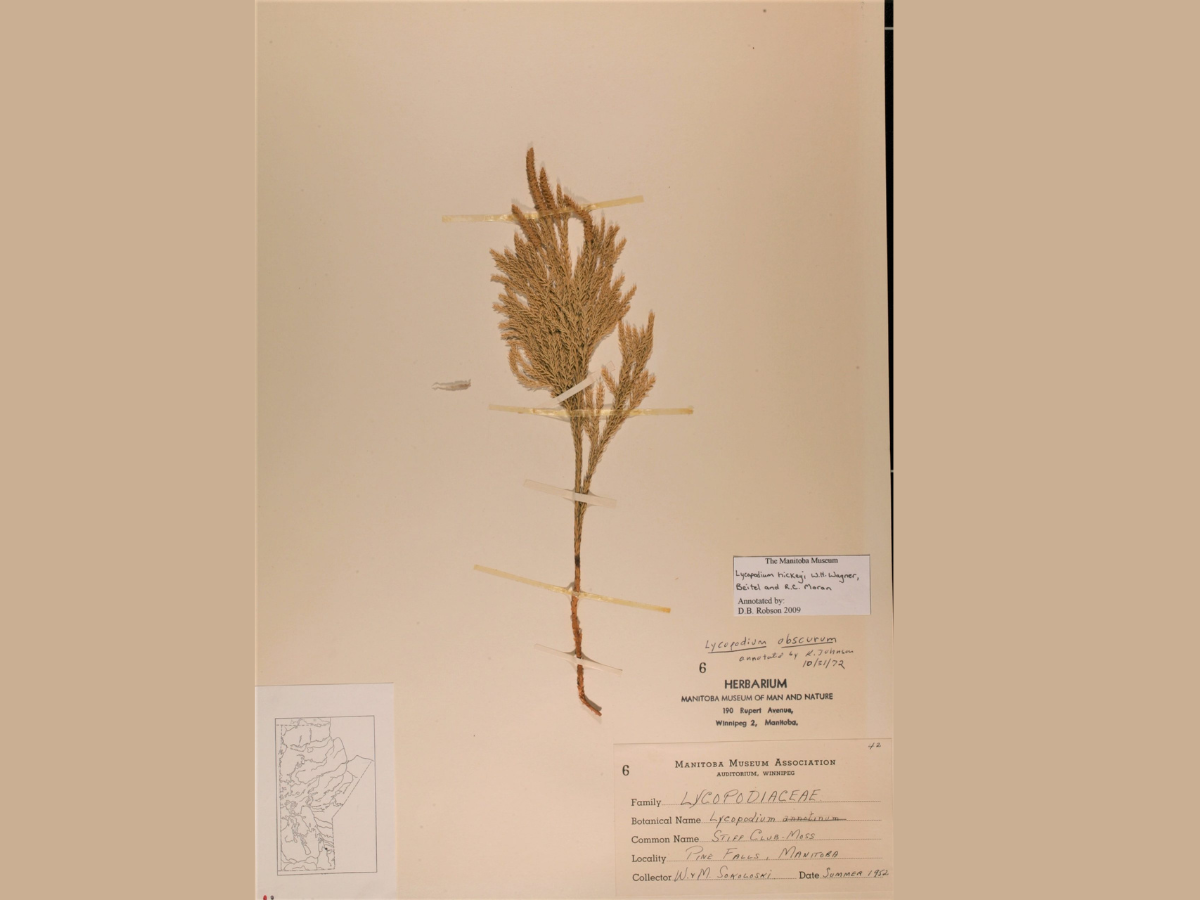

Found in House

You don’t even need to do field work to find new species! In the last several years, Museum volunteers discovered several previously unknown species in the Museum’s collection of pressed, dried plants. These preserved plants, called “herbarium specimens”, officially confirm the presence of species in the province. Along with the specimen, data on when and where it was collected are provided. The Manitoba Museum alone has over 50,000 of these herbarium specimens. What makes them so valuable is that they can be examined by experts without having to travel back to the area where the plant was collected. Scientists use them to determine the rarity of species, and understand how the climate has changed over time, among other things.

This specimen, collected in 1954, was recently determined to be a newly described species, Hickey’s Club-moss (Lycopodium hickeyi).

© Manitoba Museum 000004

Image caption: Evening-primrose (Oenothera) species are hard to tell apart, even for professional botanists.

© Manitoba Museum

One of my jobs as Curator is to make sure that all our plants are identified correctly. This requires studying the most up-to-date scientific research. While examining specimens of Yellow Evening-primrose (Oenothera biennis), my volunteer and I determined that two specimens were, in fact, a species that was not confirmed to be in Manitoba until very recently: Oakes’ Evening-primrose (O. oakesiana).

Why is Manitoba a Botanical Black Hole?

So why are scientists still finding new plants in Manitoba? Part of the reason is that scientific field collecting is poorly funded. There is a widespread perception that Canada is well-explored biologically, and that there is nothing unusual left to find here. So, such expeditions are typically deemed unimportant and not funded. Another reason is that Manitoba has relatively few roads in the northern ¾’s of the province. This makes it very difficult, and expensive, for scientists to visit pristine areas where rare plants may grow.

Indigenous Contributions

When I say that a plant species is “new” to the province, what I mean is that no scientist had collected, preserved and stored a sample of that species in a registered herbarium. This does not mean, however, that no one has ever seen the plant. Someone may have seen it, but not realized that it was anything unusual.

A new species of water-lily (Nymphaea loriana) was located and documented thanks to Indigenous guides from Cross Lake First Nation.

© Manitoba Museum

As the stewards of large tracts of undisturbed land, Manitoba’s Indigenous peoples are likely aware of the presence of plant species that professional botanists do not know much about. The Manitoba Museum is beginning to work with Indigenous peoples to incorporate their knowledge on the distribution and rarity of the province’s plants into our database.