Posted on: Tuesday August 3, 2021

By Maureen Matthews, Past Curator of Cultural Anthropology

For the commemoration of the 150th Anniversary of Treaty Number One, three Treaty medals from the Manitoba Museum will be on display at Lower Fort Garry. Although these medals were used by Canada to acknowledge promises made by the Crown to First Nations people in Treaty negotiations, they also reveal a history of First Nations protocols, diplomacy, and political advocacy at a difficult time.[1]

The gift of medals to honour mutual obligations in Manitoba began with the fur trade. The first HBC Chief’s medal was created in 1776 by Thomas Hutchins, Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) Chief Factor at Albany who found that among the Ininiwak who lived on the edge of Hudson’s Bay, there was an expectation that medals would be offered. Hutchins told the Governor of the company that “ … medals also are much esteemed amongst them if large, and if presented with ceremony when the Calimut [Calument or Pipe] is smoaked[sic], will be not only deemed a mark of distinction but perhaps be a means of binding the Leaders more securely in your Interest.” (quoted in Carter 2004). During and after the war of 1812, many First Nations leaders in Canada and the US were presented with medals featuring King George III in thanks for fighting with the British against the United States. By the time negotiations for the Numbered Treaties were initiated, medals were part of a 200 year long First Nations history of Treaty making and had been used to secure a range of mutual understandings, alliances, and friendships.

When we talk about Treaty Number One, the image which comes to mind is the famous handshake medal shown here, but in fact this is not the medal that was offered in August 1871 when Treaty Number One was finalized. If you look carefully, you will see that this medal is dated 1873.

The Treaty Commissioners who arrived from Ottawa in 1871 to negotiate Treaty Number One seem to have underestimated the importance of the gift of medals as a gesture of good faith and reassurance to First Nations leaders because the first medal they presented to the chiefs in 1871 was a smallish silver medal with an oak leaf wreath on one side and a standard image of the young Queen Victoria on the other. The medal was chosen from the existing stock of generic medals made by J.S. & A.B. Wyon of London, England. It was small, thin, and made no overt reference to the momentous nature of the Treaties it was meant to signify. The Chiefs who participated in the negotiations that year thought it looked a little too much like a prize at an agricultural fair, and after seven days of negotiations and months of preparation on the part of First Nations leaders, this non-descript Treaty medal seemed to the Chiefs to be an inadequate gesture. As an expression of intent, this generic medal must have worried the Chiefs because it left a feeling that Canada was not taking to heart the enormous implications of the Treaties.

The Treaty Commissioners, having registered the rebuff, returned to negotiations in 1872 with a much more dramatic medal. It was very large, 95 millimeters (almost 4 inches) in diameter, and was based on the medal struck to celebrate Canadian Confederation. The center circle has an image of Imperial Britannia as a Roman matron with a lion resting his chin on her lap and the four founding provinces, as Roman maidens, each hold a shovel, axe, paddle or scythe illustrating their province’s economic possibilities. Surrounding this Confederation image, the medal maker, a Canadian silversmith Robert Hendry of Montreal, added an 11-millimeter band which declared, on one side, “INDIANS OF THE NORTH WEST TERRITORIES,” and on the other – the side with the image of a slightly older Queen Victoria – “DOMINION OF CANADA / CHIEFS MEDAL 1872.” This medal was initially welcomed by the chiefs until it became apparent that it had been struck in copper and merely electroplated with a thin coat of silver. The Anishinaabemowin word for silver is zhooniyaawaabik, literally ‘money metal,’ and it matters if it is pure. When the silver began to peel and rub off, the Chiefs judged this medal a very shallow gesture on behalf of the Crown.

By the summer of 1873, the chiefs were restive, most particularly because oral promises made at the time of the first signing were not being written down on the Treaty documents, but also in protest that the 1872 medal had been yet another inadequate signifier of the sincerity of Canada’s promises. So it was in the summer of 1873 that the now famous 99 per cent pure silver medal with the handshake was commissioned. Like the first medal, this one was made in London, England, by J.S. & A.B. Wyon. The front features a bust of Queen Victoria and the inscription “VICTORIA REGINA.” The inscription on the reverse side reads: “INDIAN TREATY N°. – and the date 187- .” The spaces were deliberately left blank and were incised with the Treaty number and date at the moment of concluding each successive Treaty. The handshake medal was used until Queen Victoria’s death, by which time relationships had taken such a negative turn that a hollow bronze medal with Edward VII on the back was accepted with little comment.

The handshake medal has come to resonate powerfully with First Nations peoples for the promise it holds, for the idea that a respectful relationship with the Crown will be restored. But the handshake medal is still a product of the 1870s, designed in London by an engraver who had never been to Canada and had certainly never met a Treaty Chief.

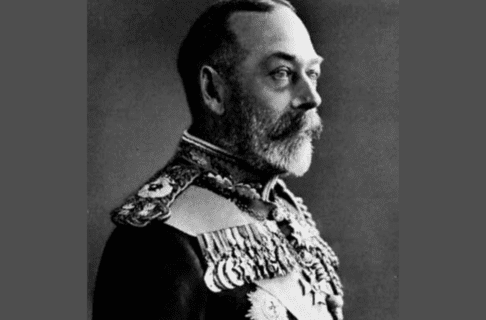

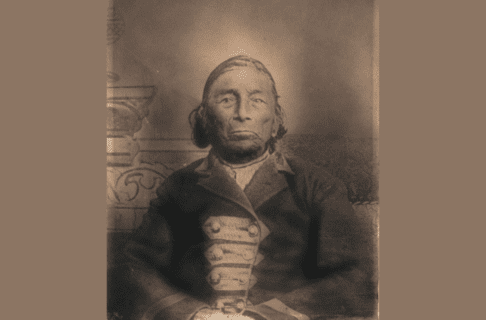

The fully clothed figure on the left side of the medal, a representative of the Queen, resembles no one more than the Prince of Wales, later King George V, although the uniform is controversial. But with Queen Victoria on the back and someone who looks like the Prince on the front, the medal is a graphic confirmation that the Treaty relationship is between the Crown of England and First Nations. The bare-chested, feather-skirted Chief, on the other hand, is problematic. Photographs of Treaty events in 1873 show crowds of men dressed in suits and it is actually quite hard to pick out the Treaty Commissioner and his party unless they are up on a dias or have a chair to sit on, because everyone present is dressed the same. The chief on the medal does not seem to bear any relation to the First Nations leaders who made Treaty Number One. The adjacent photo is of Chief Gaagige Binesi, Forever Thunderbird, also known as William Mann Sr. who negotiated Treaty Number One on behalf of Sagkeeng First Nation. The large photo, taken and printed in the 1870s, shows Chief Gaagige Binesi wearing the original Treaty Number One Chief’s coat he received in 1871. Five generations of the Mann family looked after this photo. In 2012, 140 years after it had been taken, Ted Mann brought the photo to the Manitoba Museum asking that it be used to tell the story of his famous ancestor and his role in the making of Treaty Number One. The image actively foregrounds a strong, confident Treaty Chief and provides a corrective to colonial imagery that patronizingly romanticizes Indigenous peoples and undermines their authority.

And where did this strange Indigenous imagery come from? It is probable that the engraver at Wyon in London was using as a model, an American Peace medal from the American Revolutionary War when George Washington was President. There were many iterations of this American medal over the years, but the feather skirt and strange feathers persist.

The handshake Treaty Medal is a part of First Nations Treaty history and the gesture of the tentative handshake suggesting equity alludes to a British way of making a promise. First Nations people have a long history of holding the Crown to account for these promises. And if the inescapable implication of the Treaty Chiefs is that First Nations participants in Treaty-making were “noble” but naïve, and probably incapable of understanding Treaties or their implications, the photo of Chief Forever Thunderbird provides a strong counter narrative to the racist image of primitive naiveté; the portrait shows that the chiefs negotiating the treaty were wise and thoughtful political figures. The handshake medals, as signifiers of the Treaty relationship, like the Treaties themselves, hold both the promise of sincere reciprocity and the dangers of racist condescension.

[1] Others argue that the fact of the changes were made as the negotiations proceeded through each of the early numbered treaties – as new provisions for hunting rights, rights of occupation, and a medicine chest clause were added – is evidence that there was some significant degree of First Nations agency in the negotiations taking place. In an article looking at the change in view on Treaty No, 1, Hall cites the following historians: John Leonard Taylor (1975, 1979), Richard Price (1979), John Foster (1979), Hugh Dempsey (1978), and Chief John Snow (1977). See Hall who talks about the treaty negotiation during Treaty One here.