Posted on: Tuesday January 29, 2019

Post by Angela May, Conservation Intern

The Collections and Conservation Department hosted Angela May on her 15 week curriculum-based internship between September and December 2018. This internship was the final requirement for Fleming College’s Graduate Certificate in Cultural Heritage Conservation and Management.

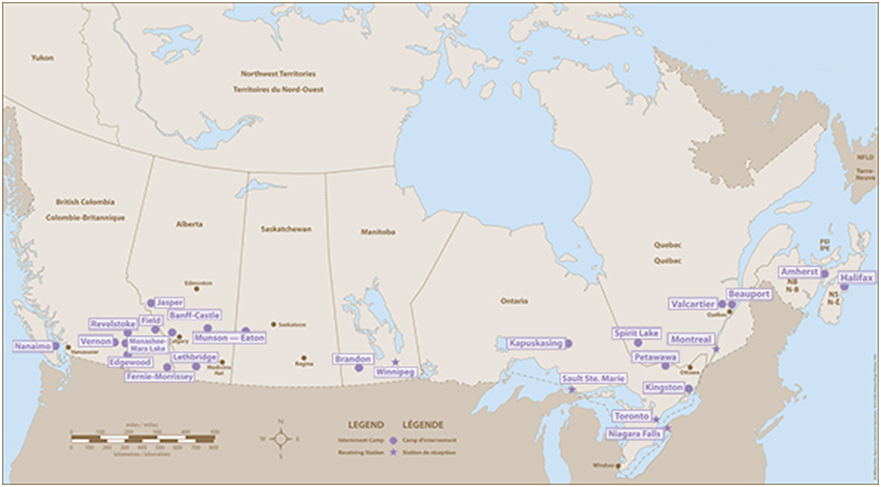

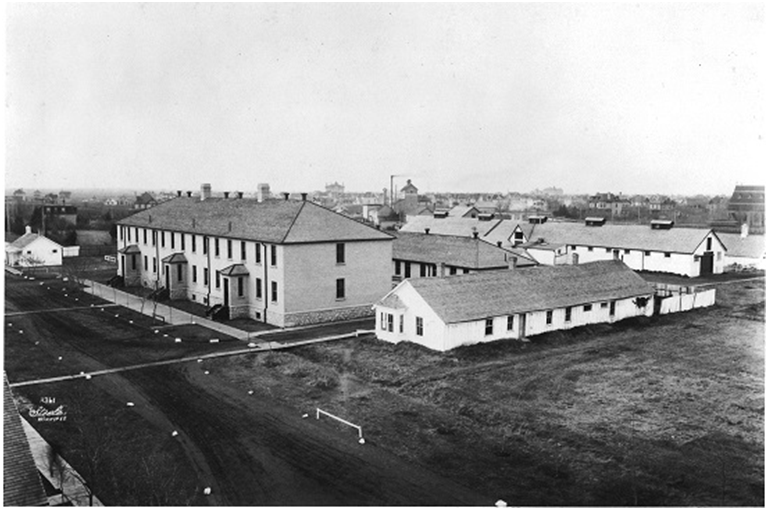

Before artifacts go on exhibition in the galleries, they come to the conservation lab for assessment and treatment if necessary. Recently I began work on preparing artifacts for the upcoming exhibition, Strike 1919: Divided City, including a streetcar sign. The sign consists of iron, glass and painted fabric. When it came into the lab the metal was corroded and dirty, the glass was covered in dust, and the two rolls of numbers painted on fabric were coated in dirt and many of the numbers had yellow staining.

In order to address these issues the sign first had to be taken apart so that each component could be worked on separately. This was done carefully, without causing any further damage, and also documented to make sure it could be put back correctly when completed.

Image: Streetcar Sign before conservation treatment showing dust and corrosion. H9-7-13 ©Manitoba Museum

First, the loose dirt and dust was removed from the iron frame using a brush and vacuum. Some packing peanuts that were caught on the interior of the frame were also removed using tweezers. Next, a fibreglass bristle brush was used to gently remove corrosion from the frame. It was a slow process to remove the corrosion from all sides of both the exterior and interior of the frame, the front of the metal straps that held the glass in place, as well as each little screw that fastened the straps to the frame.

Because the back sides of the metal straps holding in the glass were unpainted, I was able to use the air abrasive machine with plastic media to more easily and quickly lift the corrosion from these pieces.

Disassembled metal frame after corrosion was removed. ©Manitoba Museum

Metal straps prior to air abrasion. ©Manitoba Museum

Once all of the corrosion had been loosened, I again brushed and vacuumed the artifact to lift the dust that had formed from the corrosion being removed. I then “degreased” or lifted the rest of the corrosion still left on the surface with saliva and cotton swabs. The enzymes from the saliva help to lift the corrosion without damaging the painted surface like some solvents would. Science!

This took many, many swabs!

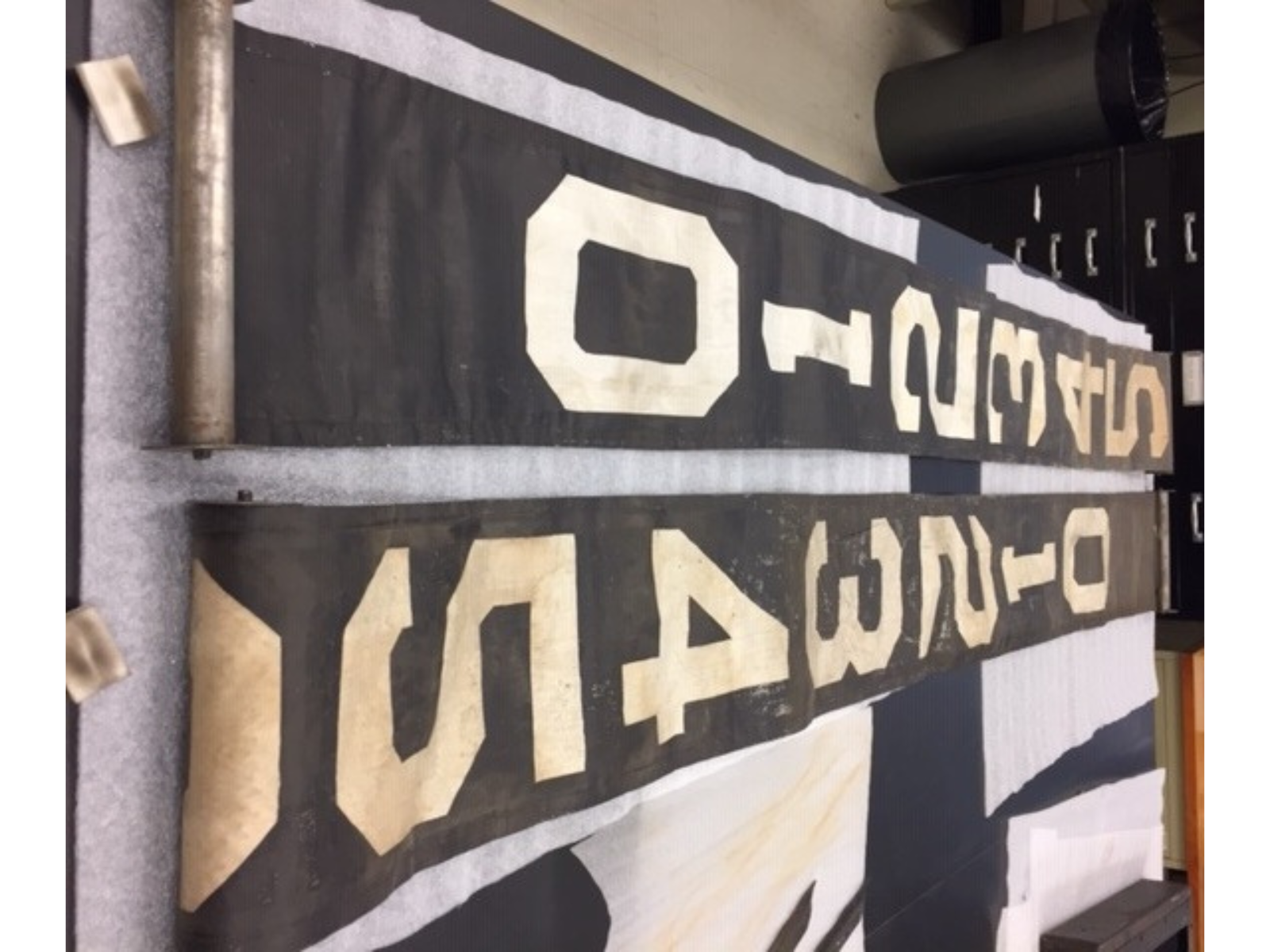

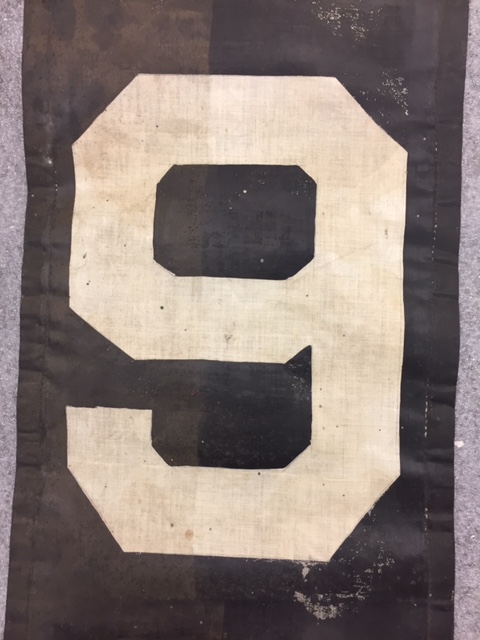

Next I began work on the textile number rolls which were covered in dirt and stains (some of the black paint was also lifting). To lift the dirt, cosmetic and soot sponges were used until they came up clean. Water and Orvus, a near-neutral pH anionic detergent, were tested on the surface to see if the yellow stains could also be lifted, but the paint was soluble in water so no further interventions were pursued.

Unrolled numbers during cleaning. ©Manitoba Museum

Detail of number before and after cleaning. ©Manitoba Museum

Finally it was time to clean the glass. To do this, a bath of room temperature water was combined with Orvus until suds were just beginning to form. The glass was placed in the bath and a soft brush was used to wipe off the dust. The glass was then rinsed and the process repeated for a second time. During the second rinse, distilled water with a few drops of acetone were used so that no residues would be left behind on the surface and so that the glass would dry a bit faster.

It was now time to reassemble the artifact. The numbers were rolled back up and fitted back into their slots and the glass with the metal straps screwed back into place.

Image: Streetcar sign being reassembled. ©Manitoba Museum

And there you have it, one clean and rust free (for the most part) streetcar sign. You can see this artifact in the upcoming Strike 1919: Divided City exhibition, which commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Winnipeg General Strike opening in March 2019.

Streetcar Sign after conservation treatment. H9-7-13 ©Manitoba Museum