Posted on: Friday October 21, 2016

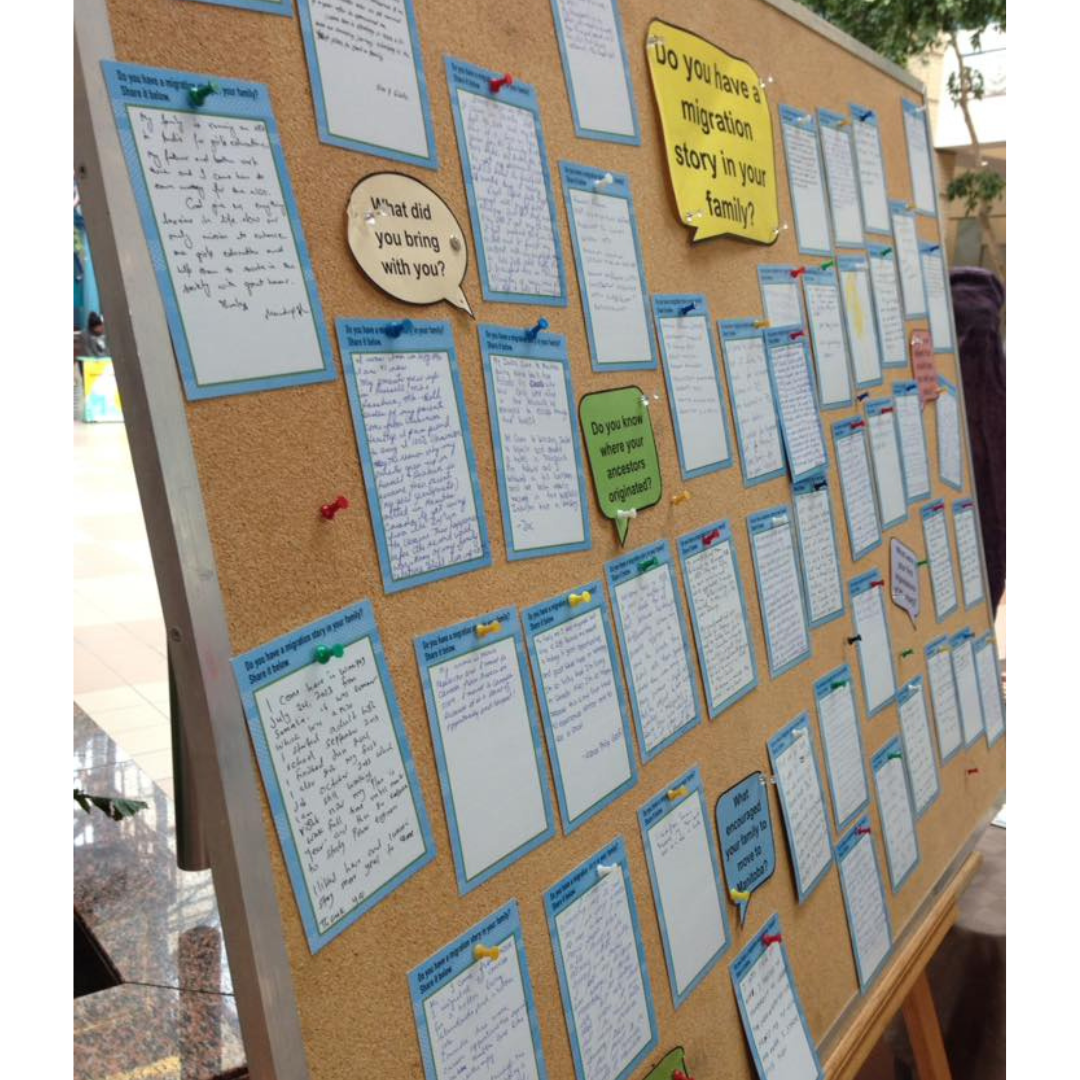

That’s right, boos and ghouls, Hallowe’en is right around the corner! And the History collection at the Manitoba Museum does not disappoint when it comes to its Hallowe’en artifacts. Let’s journey back to a time when homemade popcorn balls and plastic masks with tiny air holes prevailed…

Costumes

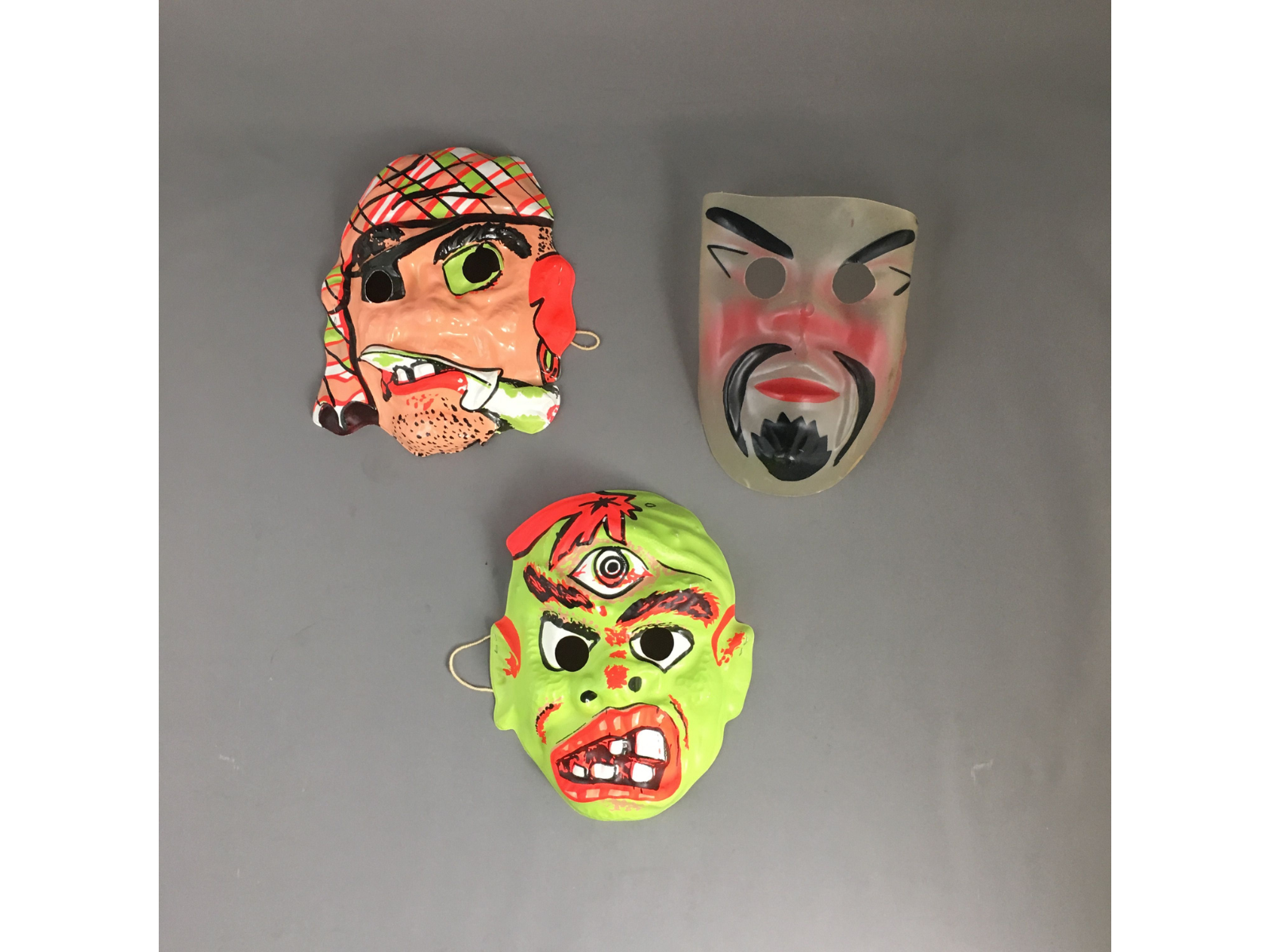

Elaborate costumes and accessories of today’s youth would shock the Trick-or-Treaters of yesteryear. While we don’t have any old sheets with eyeholes cut out by someone’s mum, we do have a selection of masks favoured by kids in the 1970s. Masks were often worn with matching plastic smocks and featured small eyeholes for reduced visibility and a layer of condensation on the inside from the wearer’s laboured breathing as they ran from house to house yelling “Hallowe’en Apples!”

Image: Children’s Hallowe’en Masks (H9-12-28, H9-12-29, H9-12-30) ©Manitoba Museum

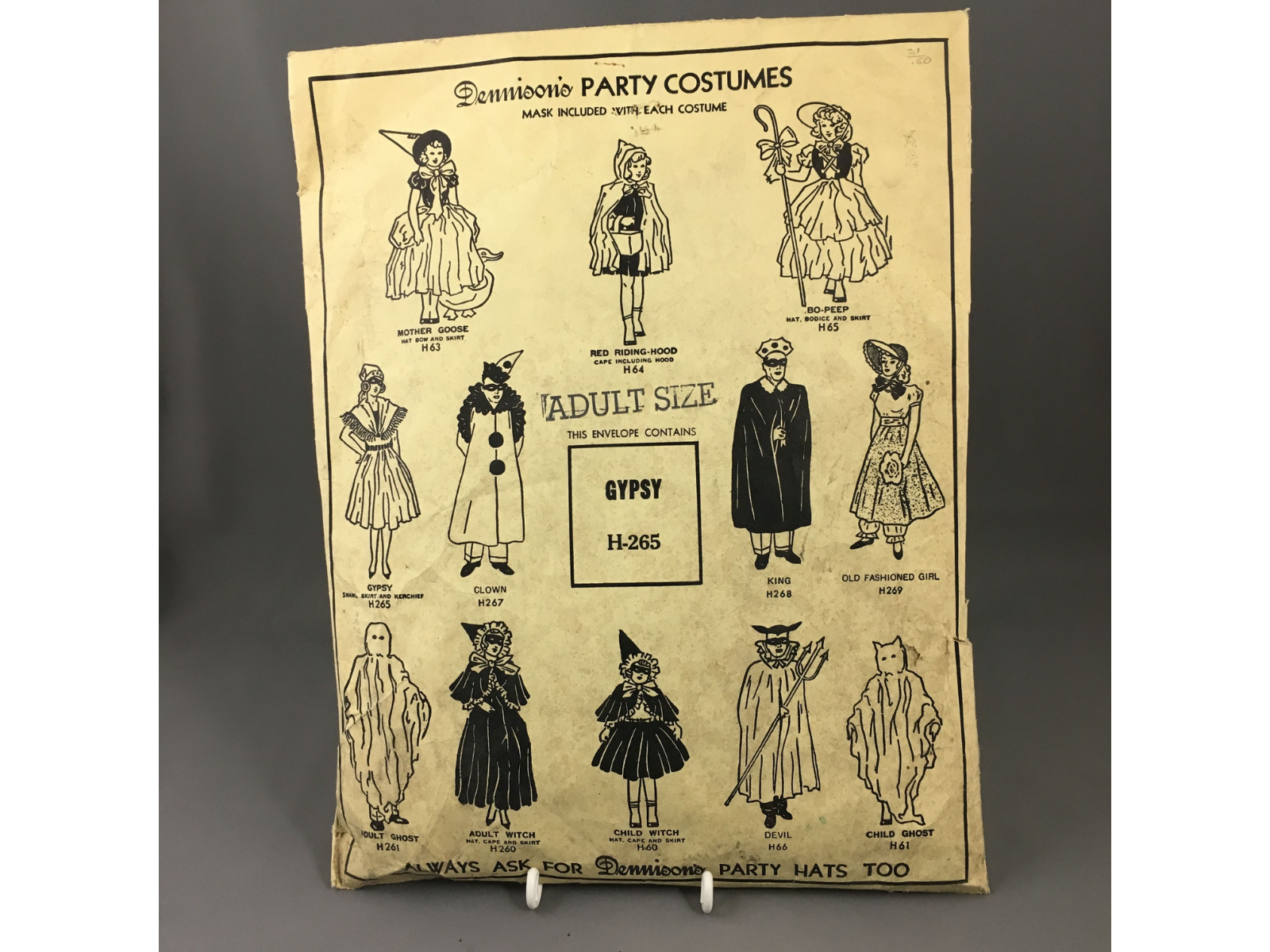

Commercial Hallowe’en costumes were being produced as early as 1910, when Massachusetts-based Dennison’s began manufacturing costumes out of paper. This Dennison’s “Gypsy” costume was sold locally at the Ukrainian Booksellers and Publishers store, formerly Ruthenian Booksellers, on Main Street. The costume consists of a skirt, shawl, kerchief, and mask; all made from crêpe paper (so don’t forget to bring your umbrella!).

Images (below): Dennison’s “Gypsy” Party Costume (H9-16-44) ; Adult Woman’s Costume (H9-16-44 2) ©Manitoba Museum

Tricks and Treats

Trick-or-Treaters in 2016 can expect to find toothbrushes and miniature containers of Play Doh amongst the candy in their bags or buckets at the end of the night. In the 1970s, homemade treats and apples were still offered to neighbourhood kids making their rounds on Hallowe’en. A handful of sweet treats might be placed in small paper bags like the ones below.

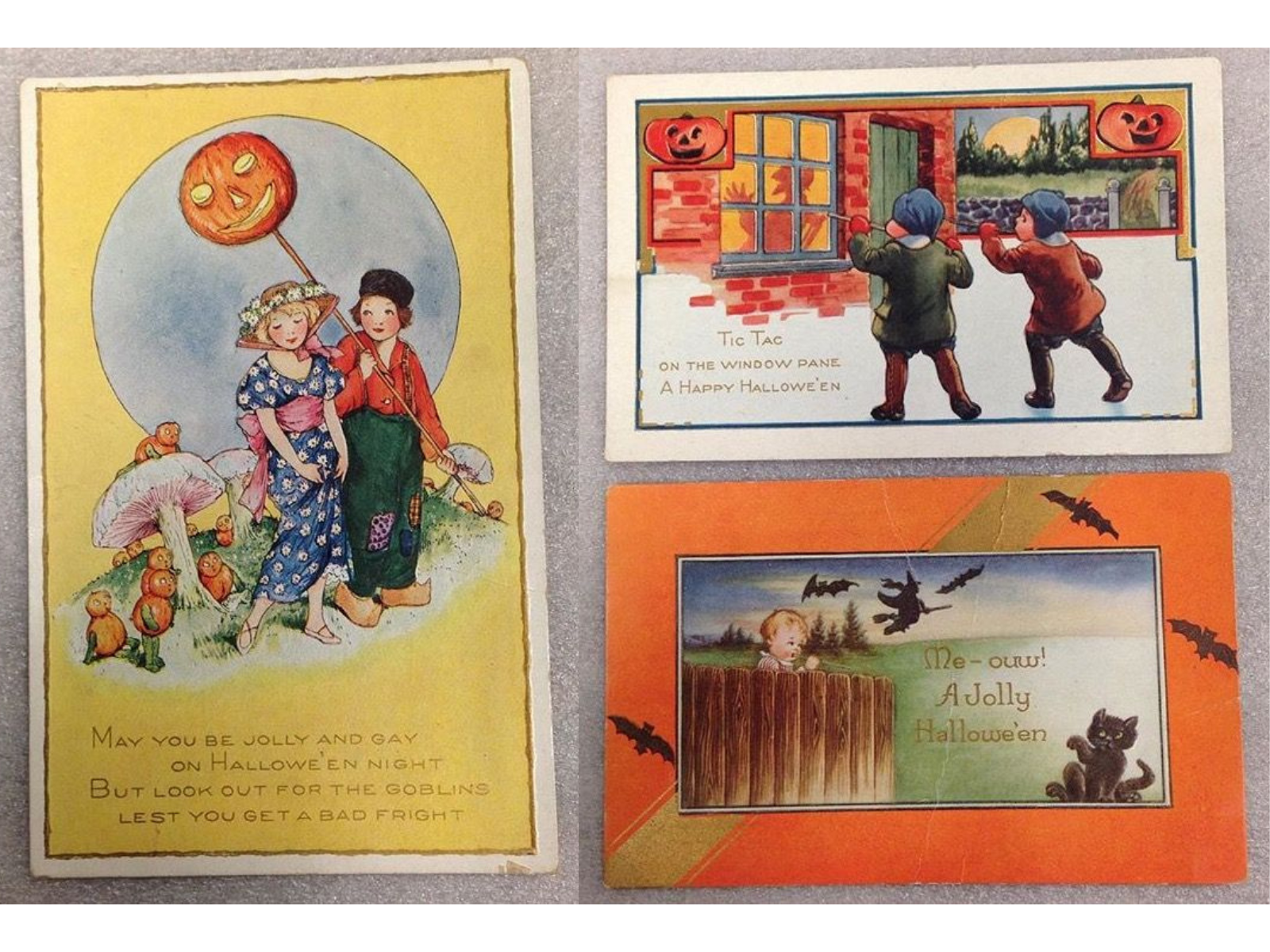

Instead of sugary goodies, in the early 20th century, a person could send their best Hallowe’en wishes to their favourite trick-or-treater with a seasonal postcard from the George C. Whitney Company, replete with jack-o’-lanterns and black cats.

Hallowe’en Treat Bags (H9-33-387, H9-33-388) ©Manitoba Museum

Hallowe’en Postcards (H9-36-240, H9-36-241, H9-36-242 ) ©Manitoba Museum

Plastic or paper, card or candy, the question remains, do you go in for the classic “Trick or Treat” or kick it old school with a sing-songy “Hallowe’een Apples”?

Happy Hallowe’en!