Posted on: Wednesday January 2, 2013

Guest blog by Alexandra Kroeger, Practicum student from the University of Winnipeg

Lately I’ve been conducting an informal survey amongst family and friends on what they know about the Urban Gallery. On the bright side, most people do know what the Urban Gallery is. Even if they don’t know it by name, as soon as I explain it as, “You know. The street? With the theatre?” people know exactly what I’m talking about. If the person was around in the 70s, they’ll probably add, “didn’t they used to sell candy there?” (They did.)

Once I ask what the Urban Gallery represents, however, I start getting blank looks. For the record, those who answer “Winnipeg in the 1920s!” are absolutely correct. But even these perceptive individuals would be surprised to learn that originally, there was a lot more to the Urban Gallery.

When the gallery was being planned in the early 1970s, the people on the committee kept coming back to the idea of contrasts in cities. Winnipeg is particularly rich in contrasts, one of the more obvious being the sharp divide between the north and south ends of the city. This contrast was particularly stark in the 1920s. Wages hadn’t kept up with rising costs of living, leaving the poor (who generally lived on the north side of the CPR tracks) barely able to get by, while the rich (who generally lived south of the tracks) got richer and richer. These kinds of tensions, along with post-war economic conditions, led to the 1919 General Strike.The Urban Gallery is set the year after the Strike, but things haven’t quite changed yet. The railroad tracks still divide the south end from the north end. The south end has a theatre, high-end clothing store and lavishly-furnished parlour; the north end, a garment factory, Chinese laundry, and a cramped boarding house.

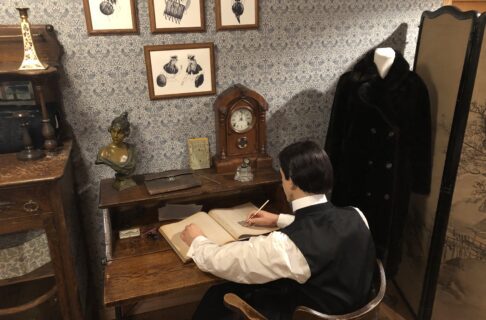

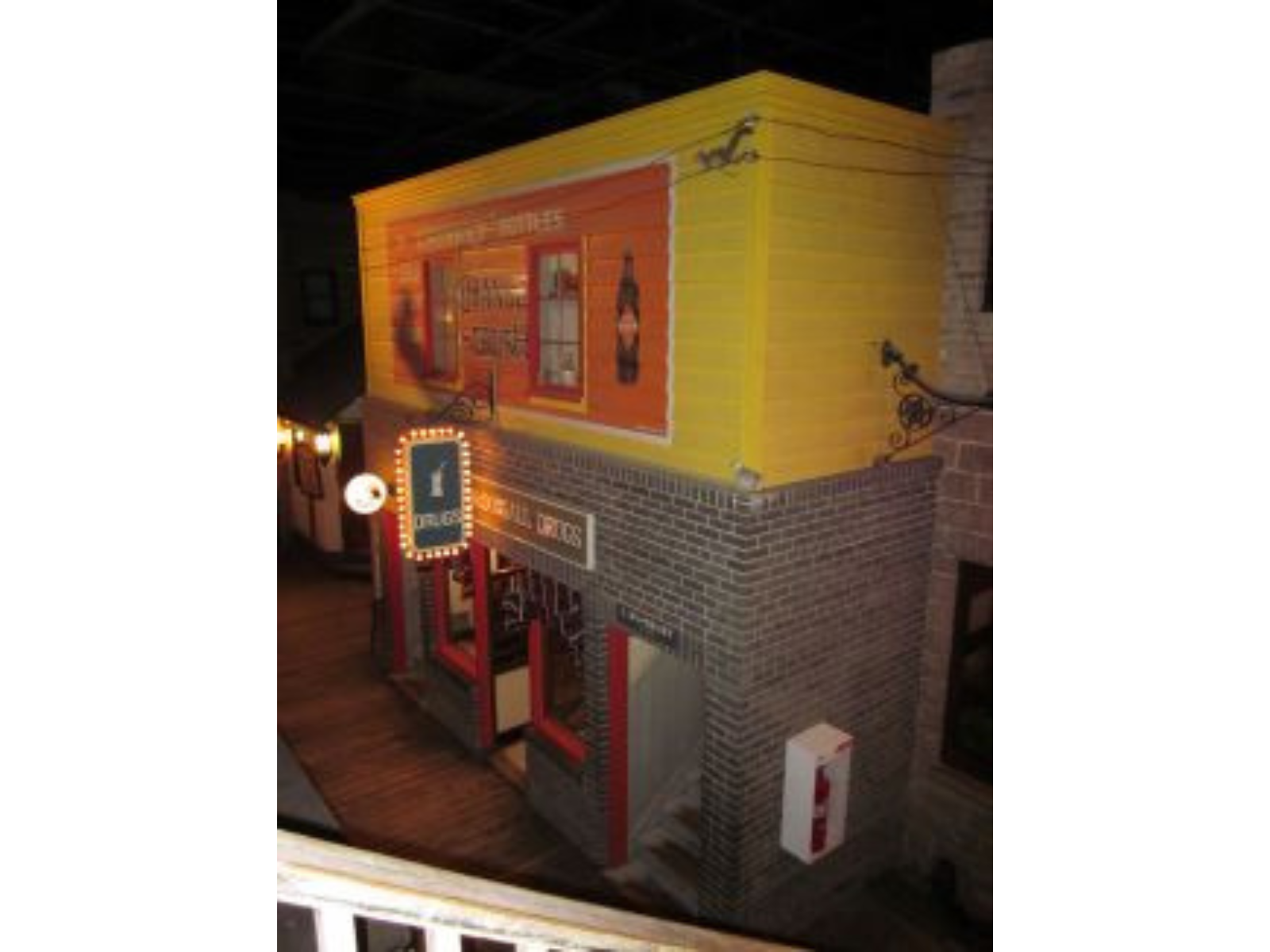

The Bletcher and McDougall Pharmacy, where at one point visitors could buy candy.

When the gallery was being planned in the early 1970s, the people on the committee kept coming back to the idea of contrasts in cities. Winnipeg is particularly rich in contrasts, one of the more obvious being the sharp divide between the north and south ends of the city. This contrast was particularly stark in the 1920s. Wages hadn’t kept up with rising costs of living, leaving the poor (who generally lived on the north side of the CPR tracks) barely able to get by, while the rich (who generally lived south of the tracks) got richer and richer. These kinds of tensions, along with post-war economic conditions, led to the 1919 General Strike. The Urban Gallery is set the year after the Strike, but things haven’t quite changed yet. The railroad tracks still divide the south end from the north end. The south end has a theatre, high-end clothing store and lavishly-furnished parlour; the north end, a garment factory, Chinese laundry, and a cramped boarding house.

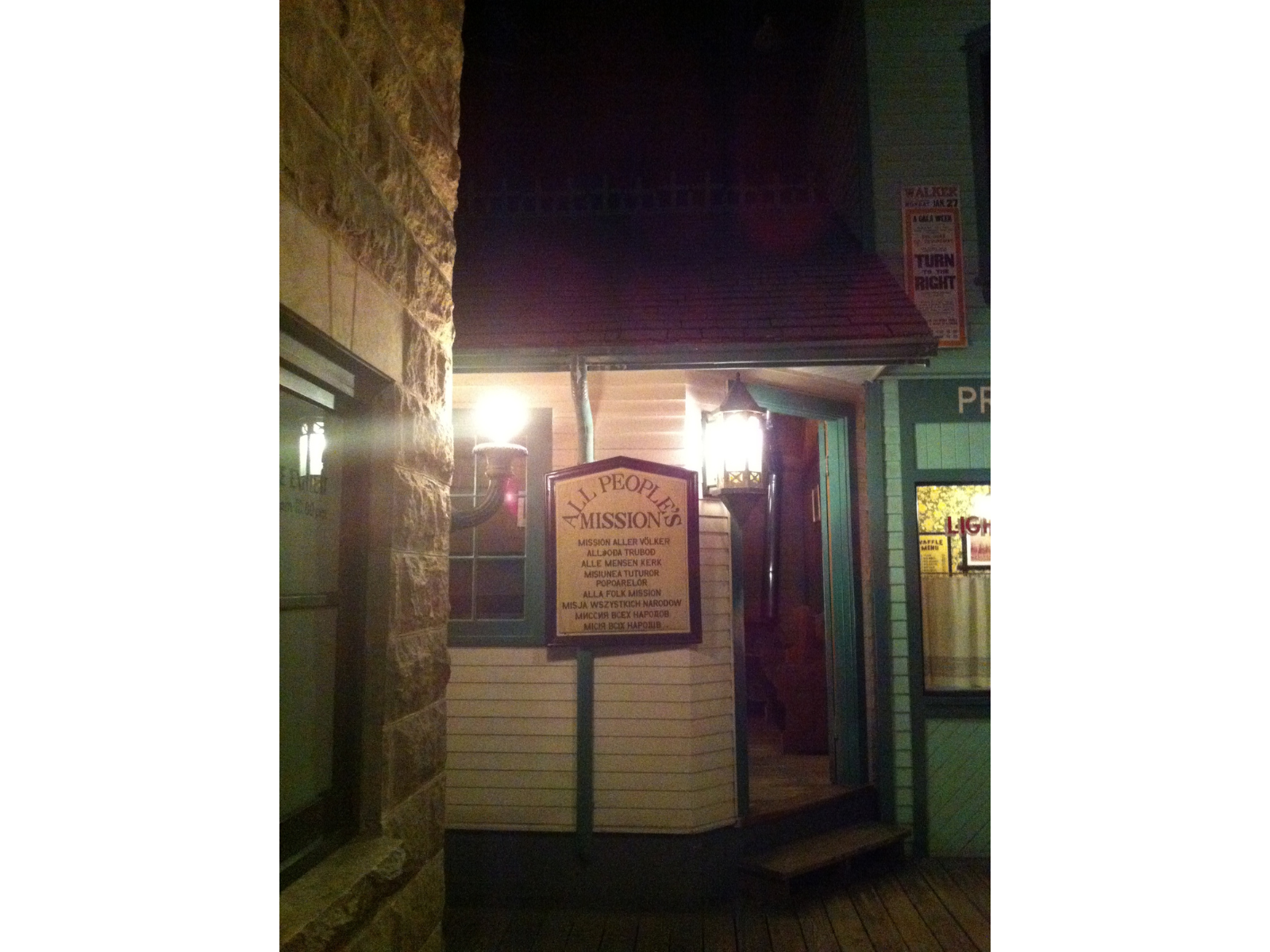

Another theme the planners wanted to explore was the past, present, and future of the city. The reconstructed buildings and businesses were supposed to represent the past, and then there were supposed to be two other components to the gallery. The Exhibition Hall by the All People’s Mission was originally an actual exhibition hall occupied by temporary exhibits on different aspects of our city’s history, and how they would affect the present. The third and last component of the gallery was “Cities of the Future,” which would have asked people to think about cities of the present and how they might develop. I haven’t figured out whether or not the Cities of the Future exhibit was actually built, but maybe a reader might have some insight.

I just want to close with a few of my favourite facts about the gallery.

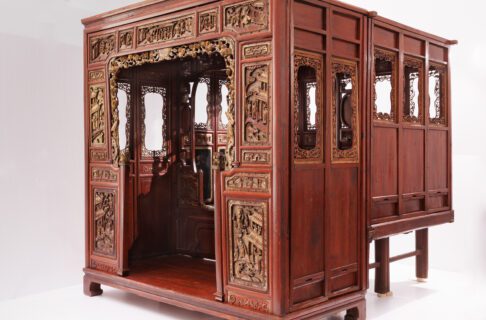

The Gum Sahn Laundry.

The All People’s Mission, possibly based on the 1904 building on Stella Ave.

Madame Taro wasn’t only a fortune teller…

There wasn’t an actual Proscenium Theatre in Winnipeg, but Winnipeg did draw several vaudeville greats.

Both the Bank of Montreal and the All People’s Mission were actual buildings in Winnipeg. The BMO building was built in the 1880s and torn down in the early 1970s – just in time to reuse some of the material from the building in the gallery. The All People’s Mission in the gallery might have been based off of the old building at Stella and Powers., though we’re not quite certain on that point.

In a particularly ironic case of contrast, the mannequin whose room overlooks the All People’s Mission in the gallery is more than just a fortune teller. Madame Taro tells fortunes, but she also provides “other services” – If you know what I mean.

There wasn’t actually a Proscenium Theatre in Winnipeg at any time in its history, but there were lots of others. Alexander Pantages used his Winnipeg theatre (which is right down the street from the museum) to test out acts for his vaudeville circuit; if it didn’t do well in Winnipeg, it didn’t make the cut. Winnipeg also drew some vaudeville greats, including Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Stan Laurel. The story goes that Bob Hope even learned to play golf here!