Last year the Rempel-Ong family donated the “Head Tax” Certificate of Yee Chung Yen, a distant relative. The family and Museum staff have been able to piece together some parts of his personal history.

Yee Chung Yen (1895-1982), later known as Henry Yee, was born in Longgang, Shenzhen District, China, and immigrated to Canada in 1917. He was forced to pay a $500 “Head Tax” to enter the country, part of a racist Canadian policy to restrict Chinese immigration. By the time the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed back in 1885, over 15,000 Chinese labourers had come to Canada to work on this difficult, nation-building project. After the work was done, restrictions were put in place to severely limit Chinese immigration. The “Head Tax” was implemented from 1885 until 1923, and was then replaced by the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred all Chinese immigration until 1947. In 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized for these discriminatory laws and the hardship they created for Chinese Canadians.

Despite the burdens of the Head Tax and Chinese Exclusion Act, Yee Chung Yen persevered. By 1923 he was working at the Subway Café at 250 Osborne St in Winnipeg, which was managed by a Mr. Yee Too. Yee Chung Yen later owned Yee’s Café in Portage la Prairie in the 1950s. The Chinese Exclusion Act had severe consequences on his personal life. Yee Chung Yen was married in China before he arrived in Canada in 1917, and the couple had two children, but Yen would never see his family again. From 1923 to 1947 his wife and children were barred from entering the country because of the Exclusion Act, Yen was never able to return to China, and they didn’t reunite afterwards.

Head Tax Certificate of Yee Chung Yen, 1917.

Surviving certificates are extremely rare today, and they help tell the story of resilient Chinese immigrants from the early 20th Century who were subjected to discriminatory Canadian policies and attitudes. H9-39-967

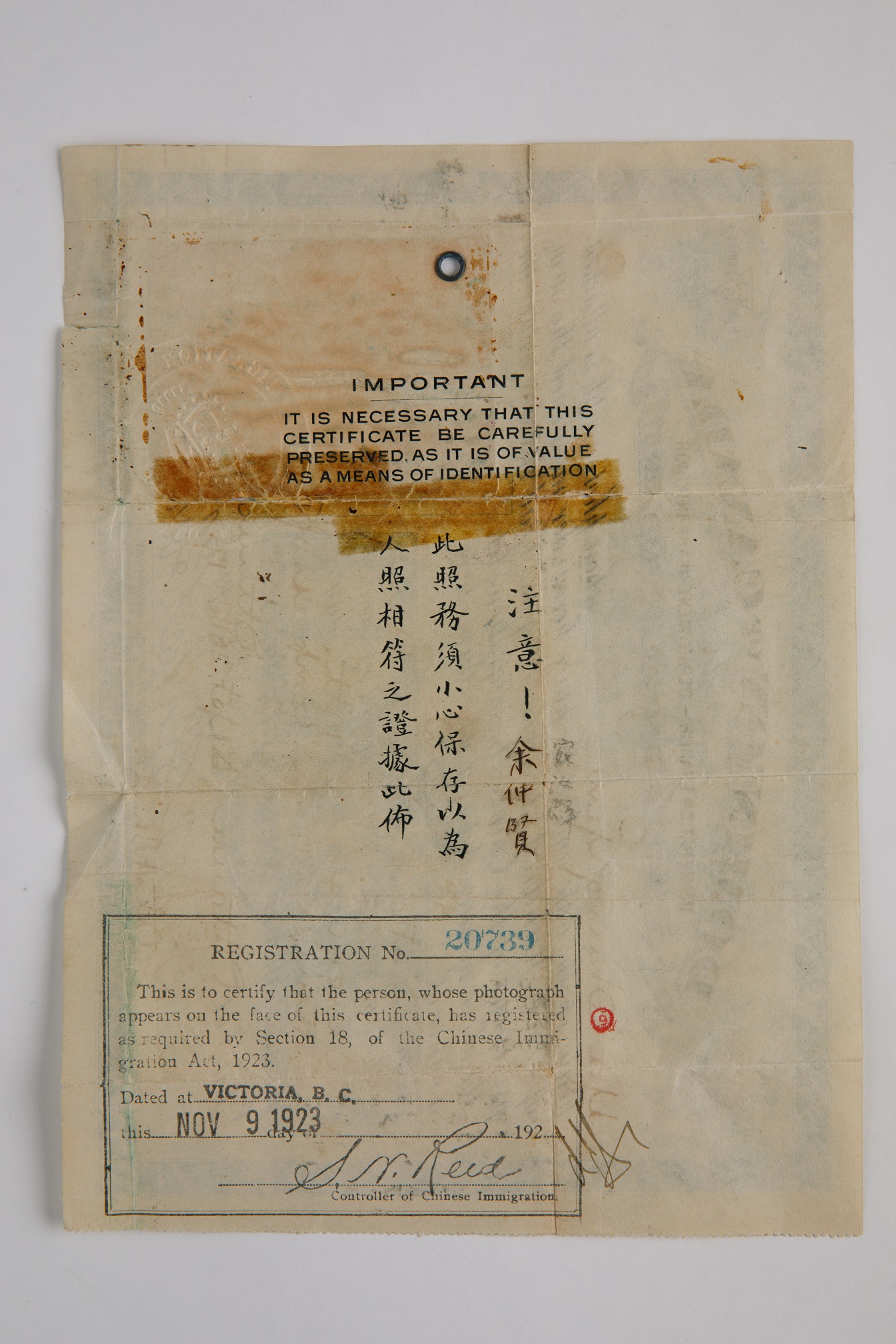

Head Tax Certificate, 1917 (reverse).

On the back of the certificate is the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act (or Chinese Exclusion Act) registration stamp. It indicates that Yee Chung Yen was registered and under observation by Canadian authorities. The Act came into effect on July 1. Though other Canadians celebrated Dominion Day at that time, Chinese Canadians called it “Humiliation Day.”

Like other Chinese immigrants, he was not allowed to bring family to live with him in Canada, and his movement outside of the country was strictly regulated. This system was in use for all Chinese Canadians until 1947. H9-39-967

Yen was instrumental in helping Mr. Don Wing Ong settle in Portage la Prairie in the 1950s. Refugees from mainland Communist China, Don and his wife Kwan (Anne) and their son Bill made it to Hong Kong, and would eventually all live and work in Winnipeg. Bill graduated from medical school at the University of Manitoba and became a well-respected doctor in the city. When Yee Chung Yen became ill and then died in 1982, Don paid some of the medical bills and the funeral expenses. Don quietly visited the grave of Yee Chung Yen at Brookside Cemetery every year until Don’s own passing in 2019.

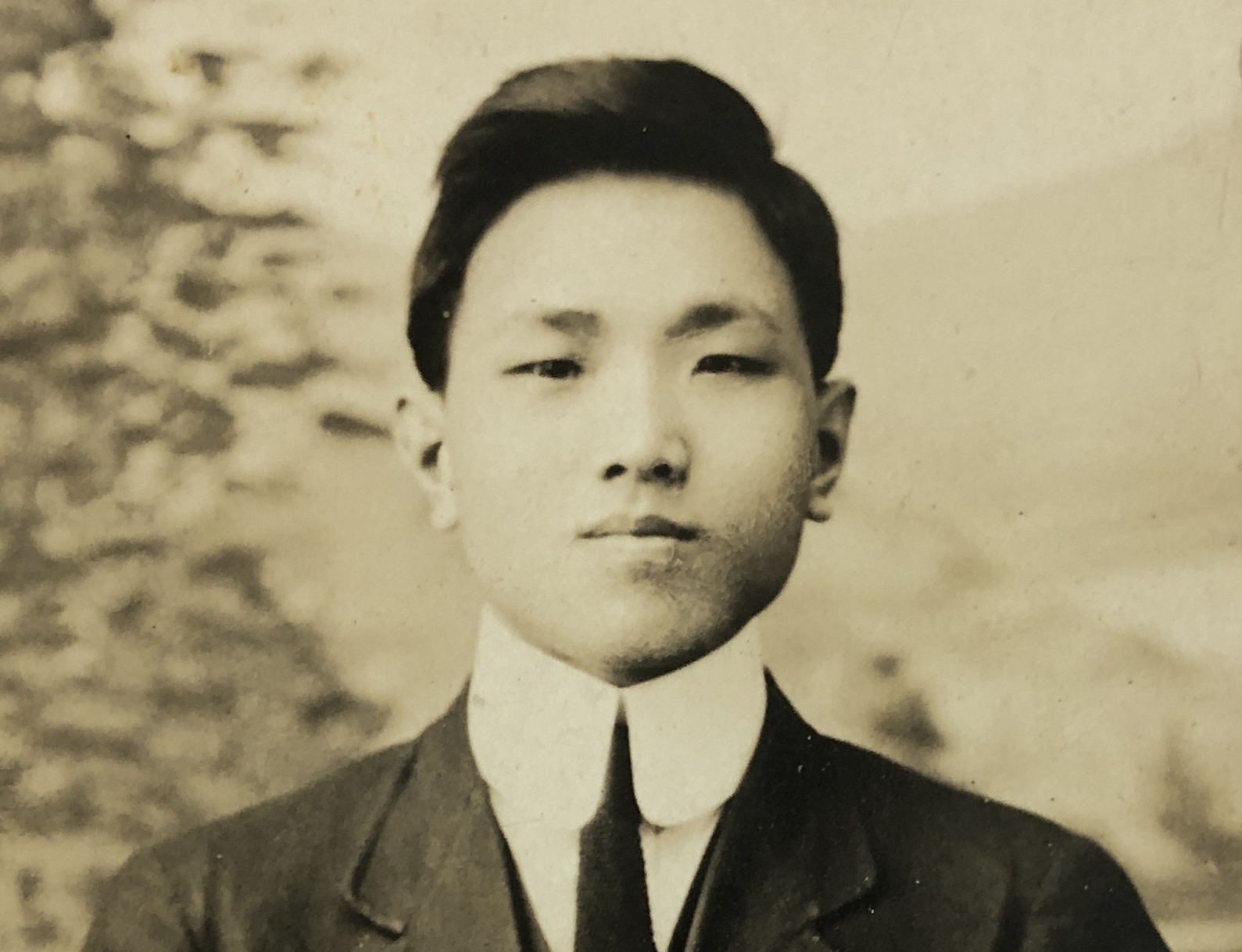

These photographs document the life of Yee Chung Yen (1895-1982).

Clockwise from top left:

1. Circa 1900. Yee Chung Yen with mother in China. H9-40-10

2. 1920 in Victoria, BC. H9-39-988

3. 1923, working at the Subway Café on Osborne St., Winnipeg, MB. H9-39-984

4. 1930s. H9-39-994

5. Circa 1952, at Yee’s Cafe, Portage la Prairie, MB. H9-39-981

6. 1970s, Winnipeg. H9-40-3

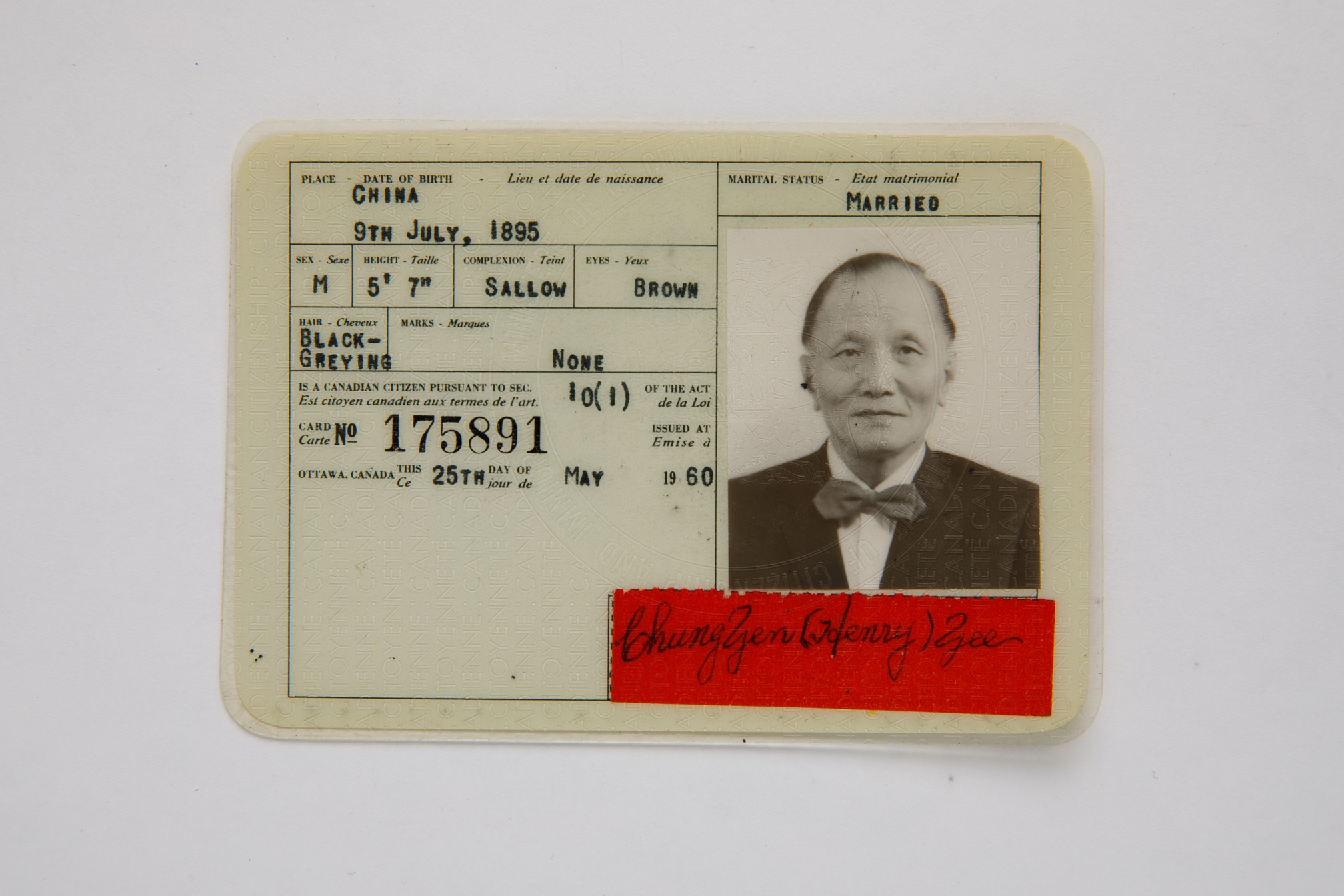

Certificate of Canadian Citizenship, 1960.

Yee Chung Yen (Henry) received full Canadian citizenship in 1960, 43 years after arriving in Canada. H9-39-968

The story and images of Yen Chung Yee will soon be featured in the Winnipeg Gallery digital kiosk.

Along with pictures and documents related to Yen, the Rempel-Ong donation includes many items that recount the story of the Ong family as they immigrated and settled in Canada.

We hope to feature their story on video soon.