Fungi grow just about everywhere and yet we are usually ignorant of their presence until they produce mushrooms in our lawns or mold on the food in our fridge. Although they are common components of ecosystems (and, disconcertingly, our fridges!), and essential for nutrient recycling, we actually know very little about them.

You can see many species of wild mushrooms and fungal hyphae in the Manitoba Museum’s spectacular “Decomposer Diorama”.

© Manitoba Museum

What are fungi?

A long time ago, fungi were considered plants because they don’t move like animals do. But fungi are actually a completely unique group of organisms. Unlike plants, they cannot produce sugar via photosynthesis. They also have cell walls made of chitin not cellulose, like plants do. Chitin is actually the same material found in insect exoskeletons. Thus, fungi are actually more closely related to animals than plants. However, unlike animals, they obtain nutrition by absorbing, not ingesting, food. Animals put food into their bodies but fungi put their bodies into food!

Giant Western Puffball (Calvatia booniana) is a common fungus that erupts from nutrient-rich grasslands before cracking open and releasing billions of spores.

© Manitoba Museum

Where fungi are found?

Fungi spend most of their lives being inconspicuous, but in reality, they are all around you. Many people know that fungal “roots” called hyphae, occur in the soil, but they are also found in places you might not expect. Fungi can be found in both fresh and saltwater environments. They also live on the outsides and insides of both plants and animals. Scientists have found at least several hundred fungal species living inside human guts, where they help us digest our food. As well, microscopic fungal spores float in the air all around us. Scientists estimate that there are 1,000 to 10,000 fungal spores in every cubic meter of air. Some fungi (e.g. lichens) have even found a way to live inside rocks!

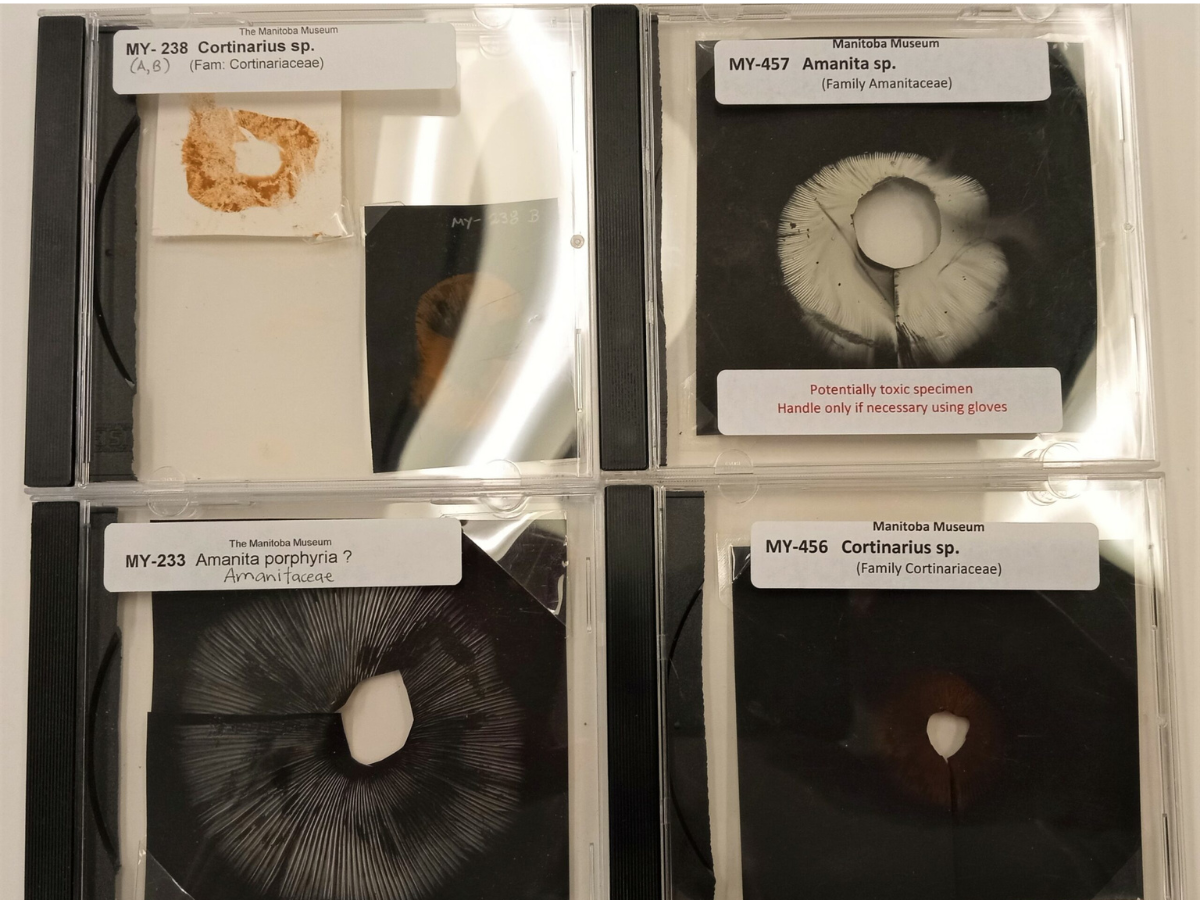

The Museum’s Curator of Botany makes spore prints of fungus she collects to help with identification. From left to right, top to bottom Cortinarius sp. MY-238, Amanita sp. MY-457, Amanita porphyria? MY-233, Cortinarius sp. MY 456

© Manitoba Museum

What do fungi eat?

Most fungi are saprophytes, which means they digest dead plants and animals. By doing so, they release the nutrients back into the ecosystem for other plants and animals to use. They are part of nature’s recycling crew. However, some fungi also poison or trap microbes like nematodes (tiny worms) to get protein, so they are at least partly carnivorous.

Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) will poison and eat nematodes (tiny worms) when they run out of wood to eat.

© Manitoba Museum

Many fungi are parasitic on living organisms. If you’ve ever had athlete’s foot or ringworm, you’ve been parasitized by a fungus!

Fungal diseases can devastate plant, animal and human communities. The Irish Potato famine was caused by the introduction of a fungal potato disease from South America into Ireland. Right now, many of Canada’s bats are dying of White Nose Syndrome caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans.

Not all fungal relationships are negative though. Many fungi form mutually beneficial relationships called mutualisms, with algae and plants. Mycorrhizal fungi interact in a positive way with plants, receiving sugar in exchange for water and minerals. Most plant species (~90%) form mycorrhizal interactions with fungi. Lichens are communities of fungi living together with algae and cyanobacteria. They inhabit areas where neither organism could live alone, such as on rocks. In fact, lichens help create soil by breaking down rocks into smaller pieces. They also protect soil from wind and water erosion, particularly in dry areas, like grasslands.

Lichens are commonly found on rocks and rock outcrops in Manitoba.

©Manitoba Museum

Are mushrooms in Manitoba edible?

There are many species of Manitoba mushrooms that are edible, including many Boletes, Chanterelles, Chicken-of-the-Woods (Laetiporus sulphurous), Morels, Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), Puffballs and Shaggy Mane (Coprinus comatus) to name a few. However, there are also deathly poisonous ones like Amanitas (Amanita) and False Morels (Gyromitra esculenta), that can be confused with some edible species.

Make sure you can identify the False Morel (Gyromitra esculenta) shown here, before collecting true morels! This lookalike species is poisonous.

© Manitoba Museum

If you want to collect and eat wild mushrooms, obtain some good mushroom field guides, and learn how to identify both the edible AND the poisonous species found here. I highly recommend taking a mushroom foraging course, or going out with an experienced picker before eating any wild mushrooms. Only eat mushrooms that you are 100% certain you have identified correctly. Keep at least one mushroom whole and uncooked to take to the hospital in case you get sick. Collect only young mushrooms, as older ones can become inedible, toxic, wormy or woody. Also remember to forage responsibly by only collecting what you will eat, and leaving at least some mushrooms behind so that the species can reproduce.

The Chicken-of-the-Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus) grows on trees in the city and, when cooked, tastes like chicken! © Carol Hibbert

Note: The Manitoba Museum is not responsible for any illness or poisoning resulting from incorrect mushroom identification and consumption. Please forage safely!