Posted on: Thursday September 12, 2013

One of the problems with being a plant is that you can’t move away if the habitat you are growing in becomes unsuitable. Plants have thus developed a life stage that is capable of moving: fruits and seeds.

Some plants use wind to distribute their seeds. Root parasites like louseworts (Pedicularis), produce thousands of seeds that are so small the wind can blow them around for miles. The seeds of these parasites cannot germinate unless they contact the root of a host plant. Fortunately, their small seeds are blown or washed into cracks in the soil, making it easier for them to reach the roots of their hosts. Indian-pipe (Monotropa uniflora) and coralroots (Corallorhiza) also have small seeds, except they depend on special fungus in the soil to help them obtain food.

Louseworts are parasitic on the roots of other plants.

Three-flowered avens has fruits that can become airborne.

Other plants have special structures to help a fruit or seed catch the wind. Conifers and broad-leaved trees like Manitoba maple (Acer negundo), produce seeds with wings to help it glide. Milkweed (Asclepias) and three-flowered avens (Geum triflorum) have seeds or fruits with tufts of hair to catch the wind.

In tumbleweeds like bugseed (Corispermum), the entire plant dries up when the seeds reach maturity. When the stem breaks off, the plant is rolled along the ground by the wind, and the ripe seeds fall off.

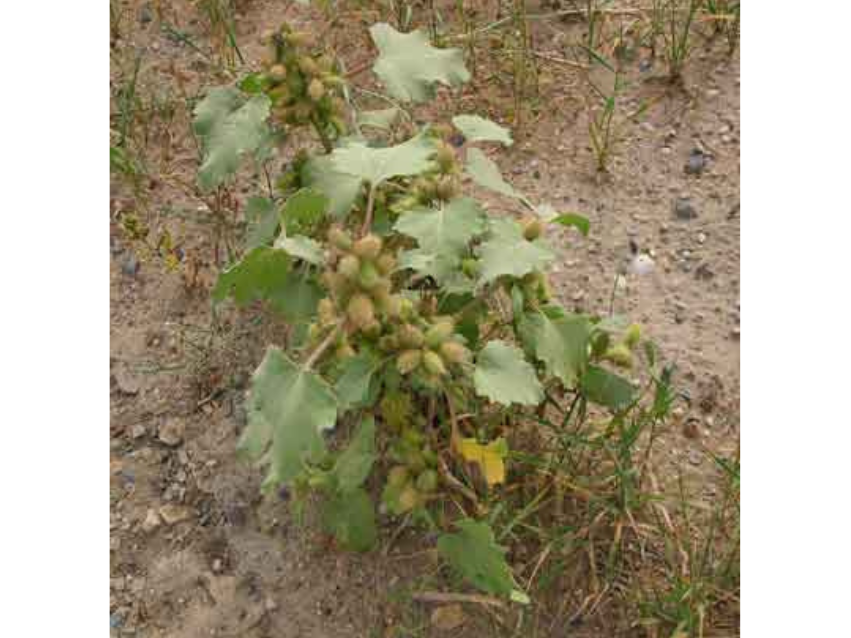

Plants also employ animals to disperse fruits and seeds. Some fruits like Cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium), have hooks that catch onto the fur of passing animals (including dogs and hikers socks!). The animals later rub off these “burs”.

Bugseed plants form tumbleweeds to disperse their seeds.

Cockleburs grow along river banks where thirsty animals congregate.

Unfortunately for plants, seeds are very nutritious. To prevent too many seeds from getting eaten by animals, species like bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) produce extremely large quantities of seeds in certain years (called “mast” years). By producing lots of seed all at once, the plant ensures that the animals will not eat all of them. As a bonus, many seed-eating animals ‘plant’ the seeds they don’t eat right away.

The development of fleshy fruits was essentially a decoy to prevent animals from consuming the seeds inside. The seeds of most fleshy fruits have a hard seed coat that makes them indigestible, and many are also poisonous: cherry (Prunus) seeds contain cyanide and apple (Malus) seeds contain arsenic. If the seeds are eaten, they simply exit the body of the animal intact and surrounded by a dollop of warm fertilizer (bonus!). To prevent animals from eating fruits before the seeds are ripe, the fruit colour blends in with the leaves of the plant. As the fruits ripen, they turn red or black and produce an enchanting smell. Who can resist?

Bur oaks acorns are buried by squirrels in mast years.

Mmmm sand cherries. Ripe and ready to be eaten by a hungry bear.

Plants have evolved many different methods to get around. If you have ever picked burs off your socks or eaten berries before, our green brethren have recruited you, too, as their courier.