CONTENT WARNING

Please be advised that this page is about the Indian Residential Schools System and deals with topics which will be shocking to many visitors. For former students, it may trigger terrible memories. We cannot change the history and can only hope that our telling of the truth will educate those who are unaware of this very Canadian story of cultural genocide.

If you or anyone with you is experiencing distress as a result of this content or pain from a residential school experience, we encourage you to take the time to care for your mental and emotional well-being.

The National Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419 and offers emotional and crisis referral services.

Image: © Manitoba Museum/Ian McCausland

The following information can also be seen in the digital kiosk in our new Schoolhouse exhibit in the Prairies Gallery, pictured here.

Thank you to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, the late Theodore Fontaine, and the Mackay Residential School Group Inc. for their work on this exhibit content.

Residential Schools in Canada

A forced separation from families, culture, and identity.

For over a century, approximately 150,000 Indigenous children were taken from their parents, families, and communities. They were raised in often overcrowded and underfunded residential schools across Canada. They were not allowed to speak their own language, and often suffered abuse. Some never made it home. The last residential school closed in 1996.

History of the Indian Residential School System

The Indian Residential School System was set up by the Canadian government in the 1880s to educate and assimilate Indigenous children into mainstream Canadian society, and to convert them to Christianity. The children were forcibly taken from their families for extended periods of time, told their Indigenous heritage and cultures were primitive and evil, and were not allowed to speak their own Indigenous languages.

Punishment, Abuse, and Neglect

Children were severely punished if these, and other strict rules, were broken. The system was criticized at the time for child neglect, made worse by the behaviour of some staff who used their authority and the isolation of the schools to abuse the students in their care. A shockingly high number of students died due to neglect, abuse, lack of food, isolation from family, disease, failed escapes, and badly constructed buildings. Students received inferior education that focused on training for manual labour in agriculture, light industry, and domestic work.

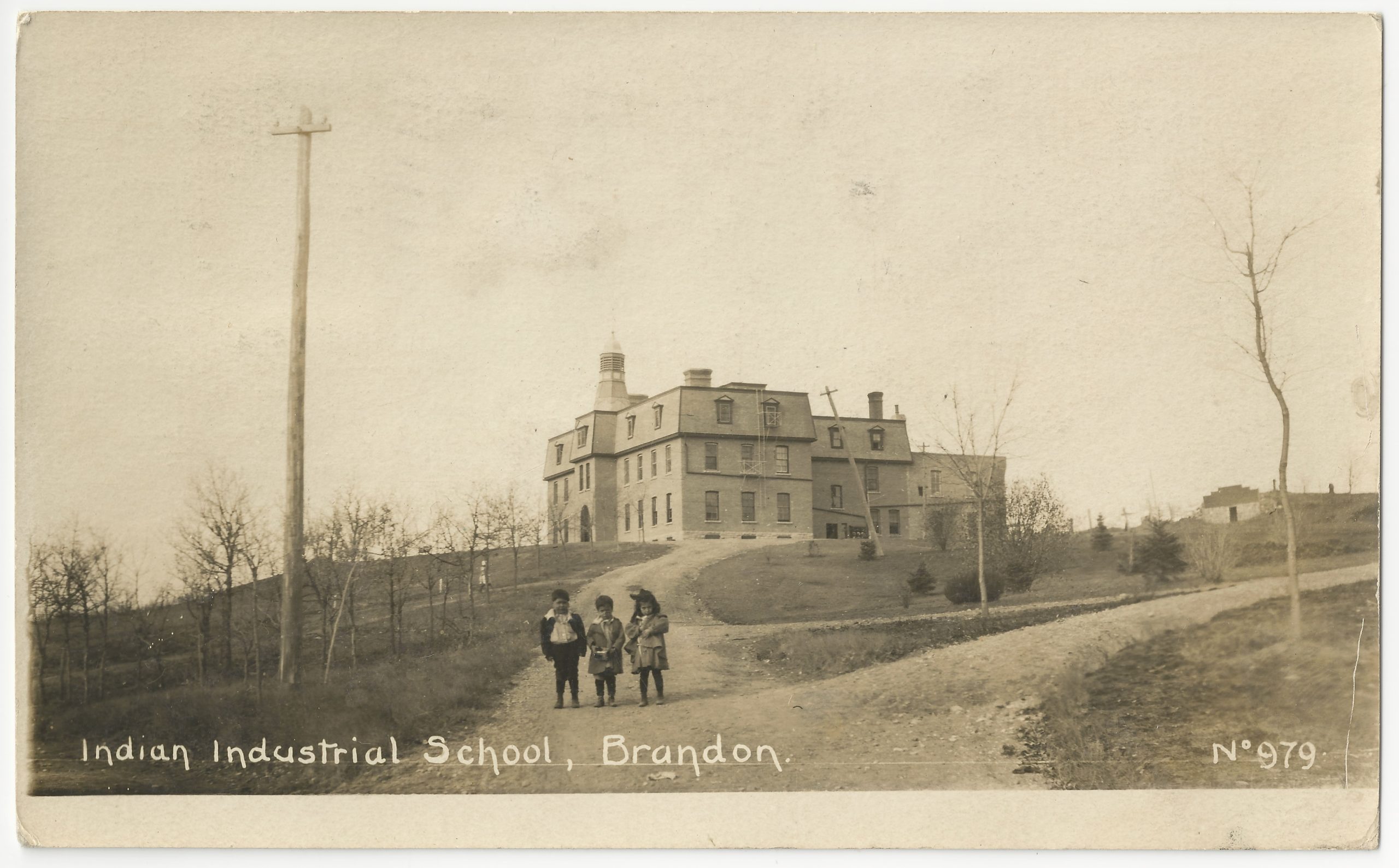

Image: Young children standing in the driveway of the Brandon Indian Residential School, c. 1908. © Rob McInnes Collection

Legacy of Residential Schools

The consequences of the Indian Residential School System were devastating to Indigenous communities, and continue to impact families today. “It visited us every day of our childhood through the replaying over and over of our parents’ childhood trauma and grief, which they never had the opportunity to resolve in their lifetimes.” (Vera Manuel, child of former students)

Canada Apologizes

Beginning in the 1990s, the Canadian government and the churches who ran the schools started to acknowledge their responsibility for an education scheme designed specifically to “kill the Indian in the child” (Capt. Richard H. Pratt, 1892). On June 11, 2008, the government issued a formal apology for the damage done by the Indian Residential School System. On September 1, 2020, it was officially announced “the residential school system will be designated as an event of national historic significance, which will help to educate all Canadians on the system and its consequences, and ensure that this part of our history is never forgotten or repeated.” (Jonathan Wilkinson, Minister of Environment and Climate Change)

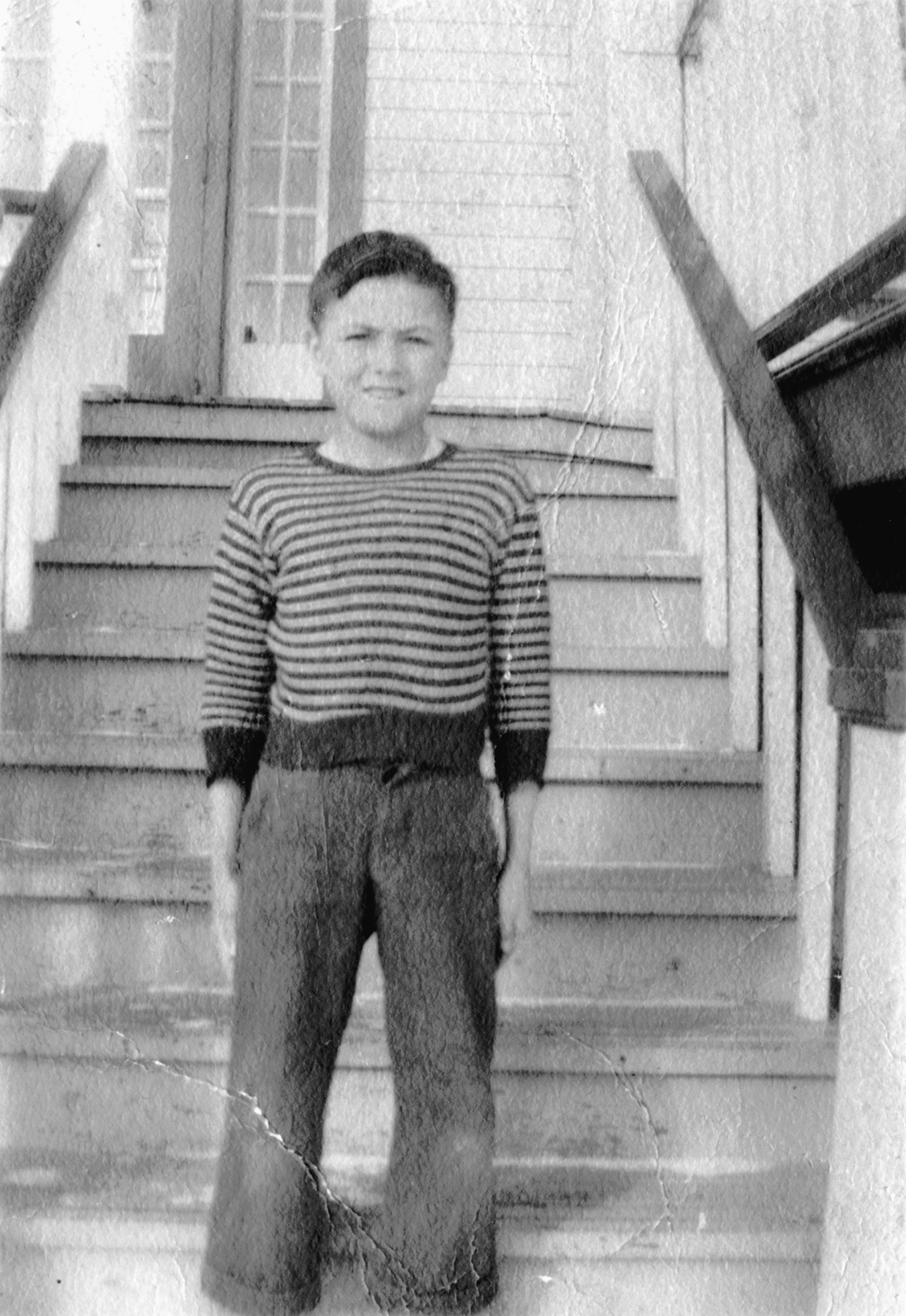

A Note on Residential School Photographs

Though there were some positive experiences at the schools, photographs that show smiling students were largely meant for a non-Indigenous audience and intended to show the institutions in a good light. These images were designed to suggest life and sports at the schools were about fun, friendships, freedom, and health. The realities were very different.

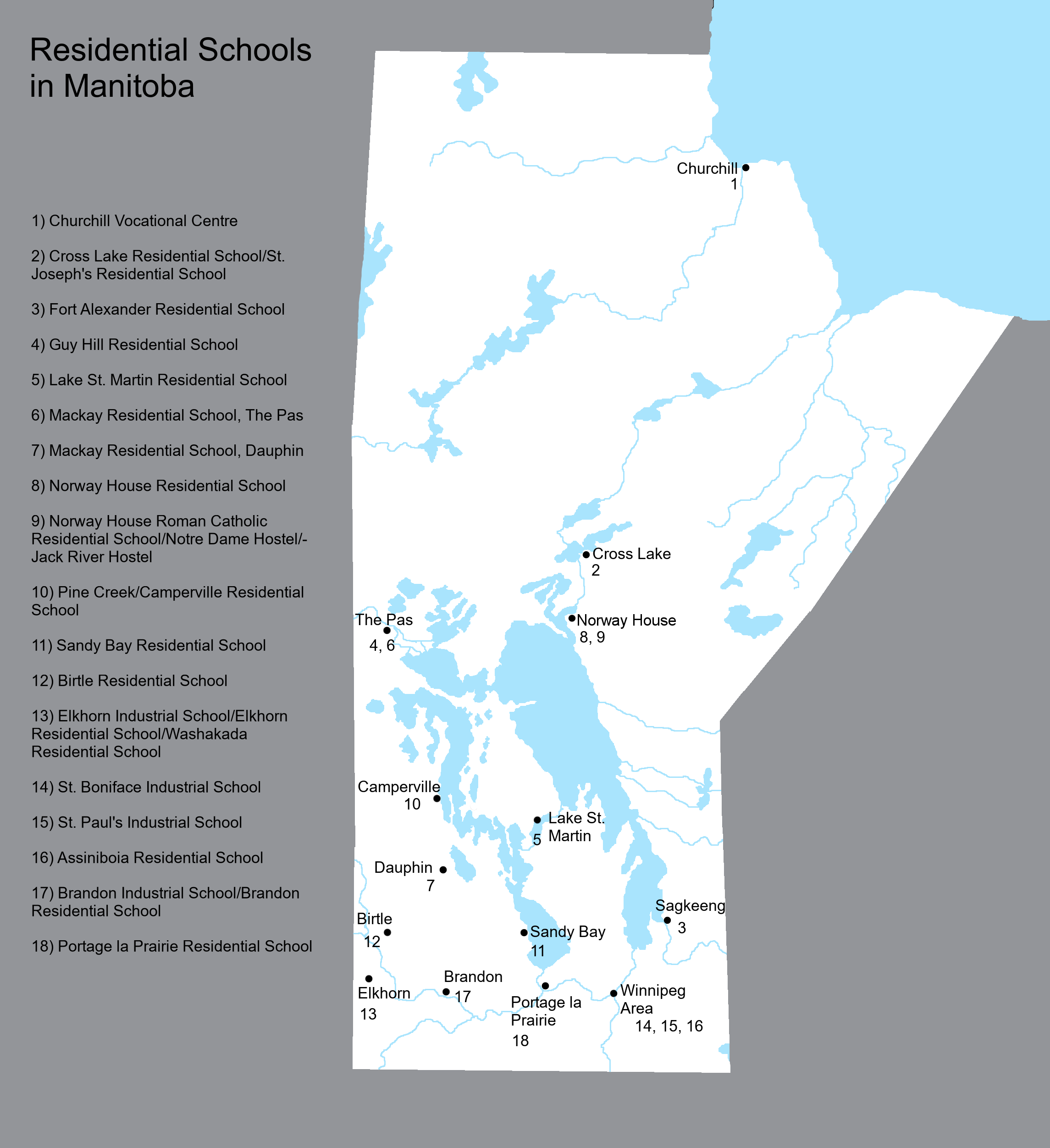

Residential Schools in Manitoba

Indigenous children from communities all over Manitoba were sent to residential schools spread across the province. There were 19 residential schools in Manitoba, including the first high school—Assiniboia Indian Residential School—which was located in the River Heights neighbourhood in Winnipeg.

1. Churchill Vocational Centre (1964–1973)

A non-denominational school whose students came mainly from Inuit communities in what was then the Northwest Territories (now Nunavut).

Left: A few buildings at the Churchill army barracks were repurposed in the 1960s for the Churchill Vocational Centre. Image: © Manitoba Museum

2. Cross Lake Indian Residential School/St. Joseph’s Residential School (1915–1969)

A Roman Catholic school under the jurisdiction of the Norway House Indian Agency.

3. Fort Alexander Indian Residential School (1905–1970)

From the beginning, many students tried running away. In 1928, two young boys drowned while trying to escape by boat.

Left: The Fort Alexander Indian Residential School was built on the Sagkeeng First Nation (formerly Fort Alexander Reserve) in 1905. Image: © National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, Missionary Oblate Sisters of St. Boniface fonds

4. Guy Hill Indian Residential School (1952–1979)

A Roman Catholic school operated by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, it was relocated from Sturgeon Landing in Saskatchewan.

5. Lake St. Martin Indian Residential School (1874–1963)

The school was operated by the Anglican Church. In 1948, a new school facility was built.

Left: Students and staff outside the school, 1920. Image: © Manitoba Museum

6. Mackay Indian Residential School (1915–1933), The Pas

The school was run by the Anglican Bishop and Diocese of Saskatchewan. In 1922, it was turned over to the Missionary Society of the Church of England in Canada.

7. Mackay Indian Residential School (1955–1989), Dauphin

After the original school in The Pas was destroyed by fire in 1933, it was relocated to Dauphin.

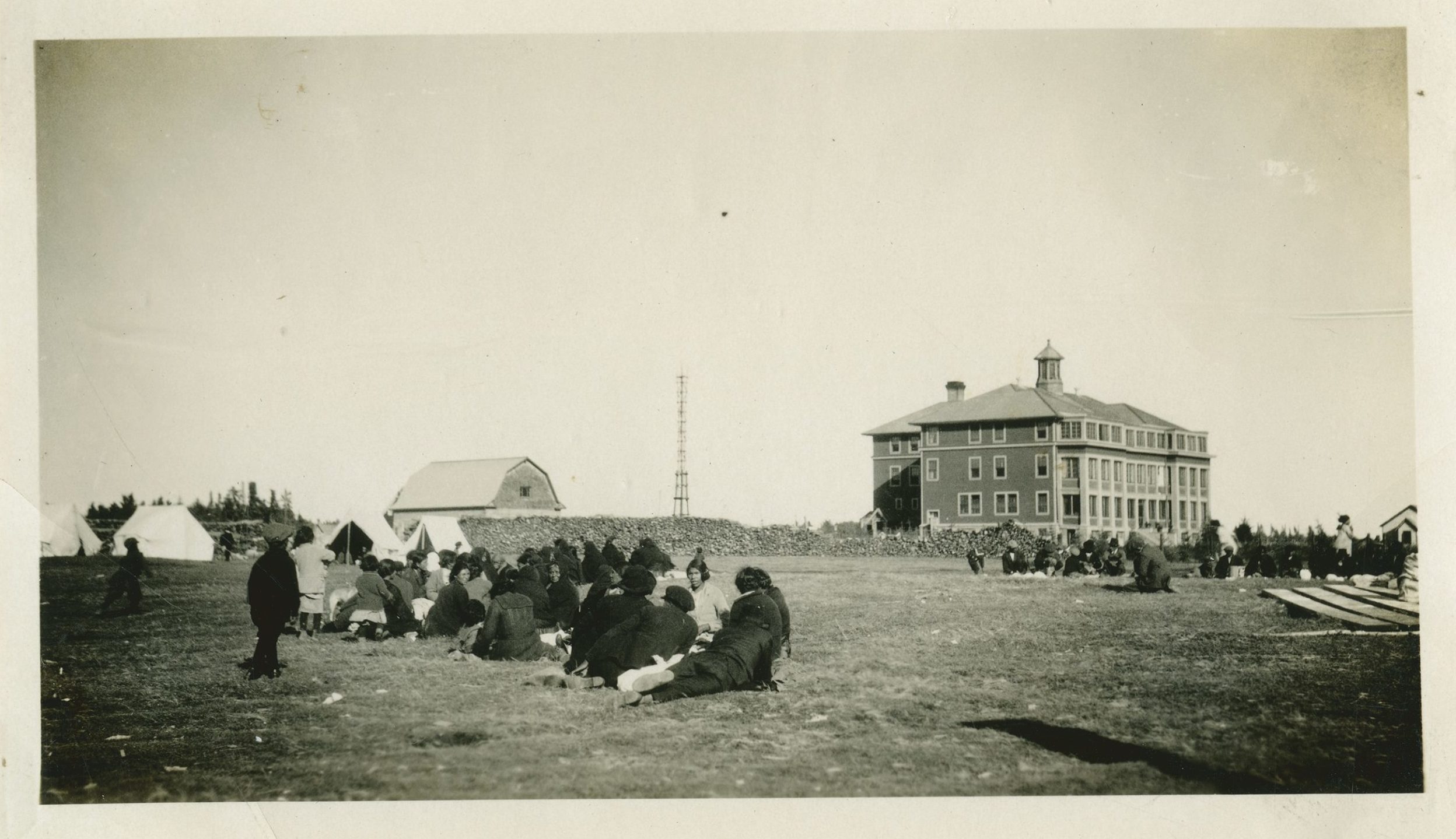

8. Norway House Indian Residential School (1900–1967)

Operated by the Methodist Missionary Society until 1925, control was transferred to the Board of Home Missions of the United Church.

Left: Indigenous families camped on the grounds of the Norway House Indian Residential School, 1925. Image: © Library and Archives Canada

9. Norway House Roman Catholic Indian Residential School/ Notre Dame Hostel/ Jack River Hostel (1960–1967)

The school was operated by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. In 1968, it became part of the Frontier School Division.

10. Pine Creek Indian Residential School/Camperville Indian Residential School (1890–1969)

The school was operated by the Oblates of Marie-Immaculate, and the Oblate Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and Marie-Immaculate.

11. Sandy Bay Indian Residential School (1905–1970)

A Roman Catholic school, it was run by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate.

Left: School exterior before it was expanded, 1939. Image: © Library and Archives Canada

12. Birtle Indian Residential School (1888–1970)

Children attended the small, local “Stone School” before a separate one was built in 1894. Originally run by the Presbyterian Church, it was transferred to the Canadian government in 1969. Children were taught agricultural methods at an onsite model farm.

Left: Families camped near the school in Birtle to visit their children. Image: © Rob McInnes Collection

13. Elkhorn Industrial School/Elkhorn Indian Residential School/Washakada Indian Residential School (1888–1919, 1925–1949)

The school was started by an Anglican priest in 1888, before being taken over by the Department of Indian Affairs in 1891. It closed briefly after a fire destroyed most of the residences in 1895, reopening in 1899.

Left: Early exterior view of the school. Image: © Gordon Goldsborough

14. St. Boniface Industrial School (1891–1909)

Formerly located near Des Meurons Street in Winnipeg, the school was under the direction of the Oblates and the Grey Nuns. It became federally owned in 1891.

Left: Staff and students standing outside the school, holding various farming and gardening tools, 1901. Image: © Manitoba Museum

15. St. Paul’s Industrial School (1886–1906); West St. Paul

Originally called Rupert’s Land Indian Industrial School and run by the Anglican Church, it was renamed St. Paul’s Industrial School when the Canadian government took it over. Students were taught various trade and domestic skills.

16. Assiniboia Indian Residential School (1958–1973)

Assiniboia Indian Residential School was located at 621 Academy Road in Winnipeg. It operated as a high school from 1958 to 1967, and as a hostel from 1967 to 1973. The school was federally funded and operated by the Oblate Fathers of Mary Immaculate and the Grey Nuns. Students ranged in age from 15 to 20 with yearly enrolment averaging 100.

The school was distinct among Canadian Indian residential schools as it was located in the middle of a provincial capital city, in the prosperous neighbourhood of River Heights. Many people living in the area did not realize the school was there; however, this does not mean it was entirely invisible. Former students remember some of the racist attitudes they experienced when they met neighbourhood residents.

Left: Assiniboia Indian Residential School, located at 621 Academy Road in Winnipeg. Image: © Société historique de Sainte-Boniface

Not all encounters were bad. Theodore Fontaine, who was among the first group of students in 1958, met young River Heights resident Morgan Sizeland while at the school. After reconnecting two decades later, they married.

As time went on, rigid school rules began to relax. Sporting teams were allowed to participate in games with other schools, then tournaments, then leagues. Students were taken for downtown shopping trips and participated in work-experience programs.

Phil Fontaine, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, also attended the school. His courageous leadership was instrumental in creating the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

17. Brandon Industrial School/Brandon Indian Residential School (1895–1972)

In 1888, the Methodist Mission Board asked the Canadian government for an industrial institute for Indigenous students in the Lake Winnipeg region. Indigenous communities were not consulted about its location and were upset when they learned that Brandon had been selected:

Left: Reverend Ferrier transporting boys from Berens River to school in Brandon, 1904. The year before, missionary James MacLachlan and six students from the community drowned in a canoe accident on their way to the school. Image: © Manitoba Museum.

“We heard we were to get Indian industrial schools in this Agency, and we were glad and would have been willing to send our children to the Institution. But now we are informed that… only one is to be established… at Brandon, we cannot really think of ever sending any of our children so far away from our reserves even for the purpose of getting an education.” (Naawigiizhigweyaash/Chief Jacob Berens, Berens River First Nation)

The Brandon Industrial School was built five kilometres northwest of Brandon. After it was converted to a residential school in 1923, it was taken over by the Board of Home Missions of the United Church of Canada. The curriculum did not focus on academics. Girls were taught cooking, sewing, and other domestic activities, while boys learned farming, carpentry, and other trades.

From 1898 to 1906, more than 25 children died at the school and their deaths were attributed to illnesses that often swept through the school. Despite this, administrators usually reported a healthy school environment and did not link these deaths to the conditions at the school. An unknown number of children died before it closed. Two cemeteries are associated with the school.

In 1969, the federal government took over, closing the school in 1972. It was demolished in 2006.

18. Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School (1886–1975)

Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School began as a small day school in 1888, run by the Women’s Foreign Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church. A group of ten women in town were so concerned about the nearby Lakota settlement not yet being “Christianized” that they provided free lunches to entice children to attend. It was soon turned into a boarding school.

Left: Students planting the fields outside the school, c. 1930. Image: © United Church of Canada.

In 1915, the school was moved so that farming and gardening would be more successful. Children at the school spent most of their time engaged in farming and domestic chores, leaving little time for academic learning. In 1925, the school was transferred to the control of the United Church of Canada.

In the 1940s, there were many runaway students. After an incident involving four girls who suffered serious frostbite, the Department of Indian Affairs looked into school conditions. It was found that the principal enforced many strict rules and punishments. Children could not speak during meals, siblings and cousins were not allowed contact with each other without permission, all doors were kept locked, staff would pull the children’s hair and rap them on the head with their knuckles, and the strap was used liberally for punishment. The principal was dismissed.

Control was transferred to Indian Affairs in 1969 and the school was used to house Indigenous students who attended classes in town. It was closed in 1975 and is now a Manitoba Provincial Heritage site, having been transferred to the Long Plain First Nation in 1980.

Stolen Children: Survivors and Their Stories

“It’s not just a part of who we are as survivors and children of survivors and relatives of survivors, it’s part of who we are as a nation. And this nation must never forget what it once did to its most vulnerable people.” (Senator Murray Sinclair, Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2017)

Jackson Beardy

Beardy was an Anishinini (Oji-Cree) artist and activist from Garden Hill First Nation. He worked at the Manitoba Museum in the early 1970s and became a leading figure in the development of professional Canadian Indigenous art practice in the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1956, Beardy and his sister were taken to residential school in Portage la Prairie. He was separated from her on arrival, and they were forbidden to communicate. He experienced the school’s attempt to crush his early traditional and cultural teachings: he was taught linear time, the English language, that his own people were “savages,” and prohibited from speaking Anishininiimowin. Beardy eventually experienced what he called “self-hate” and found himself living between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, feeling like he belonged in neither.

However, it was also in residential school that he took his first steps toward becoming an artist. Mary Morris, a kindly teacher, took notice of his natural artistic talent and encouraged him. She remained Beardy’s supporter and friend until her death in the mid-1970s.

Many children left residential school when they turned 16. The school principal promised Beardy that if he stayed and completed his high school certificate, he would help him get further professional art education. Two years later, he walked back on this promise, saying that artists were “lazy beatniks.” Beardy, he stated, was educated to be “a decent citizen who could function properly in society.” Beardy was enraged, but told the principal that he would show him—he would become an artist.

Image: Beardy (far right) with fellow Indigenous artists and Winnipeg Mayor Stephen Juba (second from right), c. 1975. © Reproduced with the permission of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

Theodore Fontaine

Just after his seventh birthday, Theodore Fontaine lost his family and freedom when his parents were forced to take him to the Fort Alexander Indian Residential School near his home in Sagkeeng First Nation. He attended the school from 1948 to 1958, transferring to the Assiniboia Indian Residential School in Winnipeg for two final years. In his own words, 12 years after he first entered the Indian Residential School System, he left it frozen at the emotional age of seven. Due to the various traumas he experienced as a student, combined with the loss of his family, community, culture, and language, Fontaine found himself on a path of self-destruction. In his late 20s, he was able to pull himself out of his downward spiral, graduating as a Civil Engineer when he was 32. His continued success included a significant and meaningful career, and extensive voluntary service. In 2010, Fontaine chronicled this journey of self-exploration and healing in “Broken Circle: The Dark Legacy of Indian Residential Schools—A Memoir.”

“Like me, most survivors waited a decade or more before going back to school. Some went back even 15, 20, or 25 years later to study the things that as children they’d dreamed of studying—law, medicine, education, etc. But Canada lost many great contributions from its First Nations citizens because of the residential school system.” (Theodore Fontaine, 2017)

A single original Assiniboia Indian Residential School classroom building remains today. It is now, ironically, the Canadian Centre for Child Protection.

Image: Fontaine on the steps of Fort Alexander Indian Residential School, 1950. © Theodore Fontaine

MacKay Residential School Group Inc.

Former students of the Mackay Indian Residential School incorporated a not-for-profit charity, the MacKay Residential School Group Inc (MRSGI), in 2010 to take control of their own healing. Many former students experienced trauma and sexual, physical, and mental abuse at the hands of their caretakers or other students. Some continue to struggle with the scars of their experience. They now gather regularly to organize annual retreats, workshops, and networking sessions, and to initiate reconciliation projects that serve their needs.

Despite everything, their childhood resilience shines through and they choose to remember that good things happened at the school. Children played games, had adventures, and laughed like children do, even in the shadow of fear and abuse. Upon leaving the school, some relationships blossomed into families, and lifelong friendships formed. People received proper education and went on to become professionals in the fields of medicine, law, teaching, nursing, science, engineering, finance, and other endeavours.

“We would not wish to paint everyone with the same brush. At Mackay there were many good, kind individual staff whose lives became entwined with ours. The institutional setting with all its inherent faults and deficiencies put vulnerable children at risk.” (MRSGI)

Image: A reunion of former Mackay students, 1990. © National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, Mackay Residential School Gathering Inc fonds (A2020-004)

Since 2017, MRSGI has worked to repatriate a collection of 59 paintings created in the 1960s by children at the school. A travelling exhibit called “There is Truth Here” honours the work of survivors by displaying their creativity and resilience as children. These paintings are now housed at the Manitoba Museum.

George Beardy

A reunion, many years in the making.

In 1959, George Beardy was an eight-year-old boy living far from his home community of York Factory First Nation, attending the Brandon Indian Residential School. That Christmas and the following Easter, he was taken in by a local family. He never forgot that kindness, and has always wanted to see them again.