Posted on: Monday January 4, 2016

Last year an interview I did for the BBC Northern Ireland documentary Brave New World – Canada aired on television (see more here). This documentary, by journalist William Crawley, is about the Irish Ulster immigrants that came to Canada and shaped our nation. I was asked to talk about John Macoun, an Irish-Canadian botanist who explored Western Canada in the late 1800s. As only a small portion of my interview aired, I wanted to post a full response to all the questions I was asked to provide some additional insight into John’s life and character.

What sort of man was John Macoun?

John was a man who was obsessed with botany, with collecting plants in particular. The thrill of discovering a new species of plant really drove him. This obsession meant that he was willing to endure a lot of physical discomfort in order to find new species.

Why is he such an important figure in Canadian history?

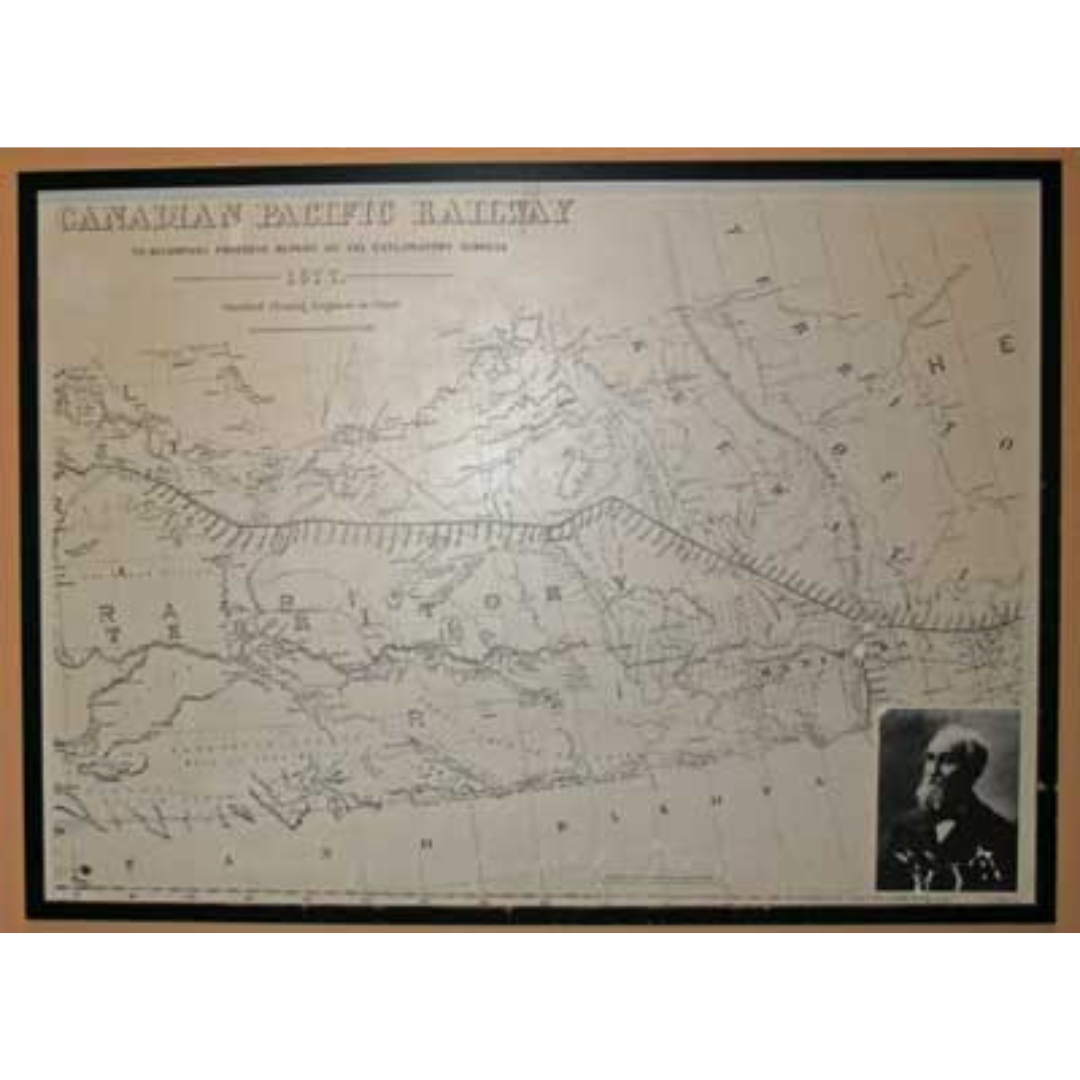

People like to say that Macoun changed the map of western Canada. Prior to his expeditions with Sanford Fleming in the 1880s, the planned railway route through western Canada was going to go through the Parklands along the historic Carlton trail, parts of which eventually became the contemporary Yellowhead highway. Macoun’s explorations, reports and speeches led people to believe that the southern parts of Alberta and Saskatchewan were just as fertile as the more northern parts. As a result, the railway went along a more southern route and many of the largest cities in the prairies, like Brandon, Regina and Calgary sprung up along it. Had the railway gone along the original route these cities may not have existed at all, or may be substantially smaller than what they are today.

Joohn Macoun, Irish-Canadian botanist.

The original 1877 Canadian Pacific Railway was set to go along a more northerly route.

Why did people think Manitoba and Saskatchewan so unsuitable for farming?

Peoples’ impressions of the prairie were largely based on a report by Captain John Palliser who travelled through the southern prairies from 1857 to 1860. Palliser described an area in southwestern Saskatchewan and southeastern Alberta as being a desert but he did have some good reasons to call it that. Palliser travelled through the area during a severe drought. His route took him through several large active sand dune complexes. Migratory Bison were still grazing the area and keeping the grasses short. To top it all off he encountered several large grass fires in the area. So the mixed grass prairies would have looked fairly desert-like at the time.

Image: Captain John Palliser travelled through dry, desert-like areas in western Canada during a drought.

Did Macoun set out to prove them wrong, or was he surprised by what he discovered?

Initially he seemed to be holding back judgement until he saw the area for himself. He was certainly happy to discover that the prairies were full of lush grasses and seemed suitable for agriculture. It was not at all like the desert he heard of. Of course had he travelled the area when Palliser did his impressions would have been different, perhaps a bit more cautionary and less enthusiastic.

What did he find as he travelled through Manitoba and Saskatchewan?

The prairies that Macoun saw were already different from what they had been when Europeans first arrived. Populations of wild Bison, Plains Grizzlies, and Passenger Pigeons were in decline. Antelope and Elk populations were also decreasing. In fact, he encountered a group of First Nations people in Saskatchewan that were on the verge of starvation because the Bison were gone. He also travelled through the area during a historic wet period. The high moisture and lack of grazing animals would have resulted in a much lusher prairie than Palliser would have seen.

What did Macoun do on this and subsequent journeys through the prairies?

John liked to get up early in the morning to collect and press plants. The plants would have been sandwiched in between blotting paper and cardboard to provide air circulation. John often spent the entire day walking to spare their pack animals, which would have been hauling plant presses, and supplies in Red River carts. Sometimes he travelled by canoe which was quite dangerous as he wasn’t particularly skilled at handling a boat. He spent a lot of time looking for areas that were appropriate for agriculture, and noting where you could get good water and timber. He recorded his observations in a journal along with comments on the weather and the distance he travelled each day.

Image: John travelled across the prairies with a Red River cart, such as this one in the Grasslands Gallery at the Manitoba Museum, to carry provisions and plant specimens.

What was his conclusion as to how fertile the land was and it’s suitability for agriculture?

Most Canadians were accustomed to farming under wetter conditions or using irrigation, as most were originally from wetter areas in Europe like England, Scotland, and France. They didn’t have much experience with dryland farming so they considered the prairies too dry for agriculture. Macoun recognized that adequate soil moisture is usually present in the spring when wheat needs it the most so he thought that cultivation of this crop was possible. Unfortunately, he underestimated the frequency and severity of droughts and during the dirty 1930s much of the farmland in the driest areas of the prairies was abandoned.

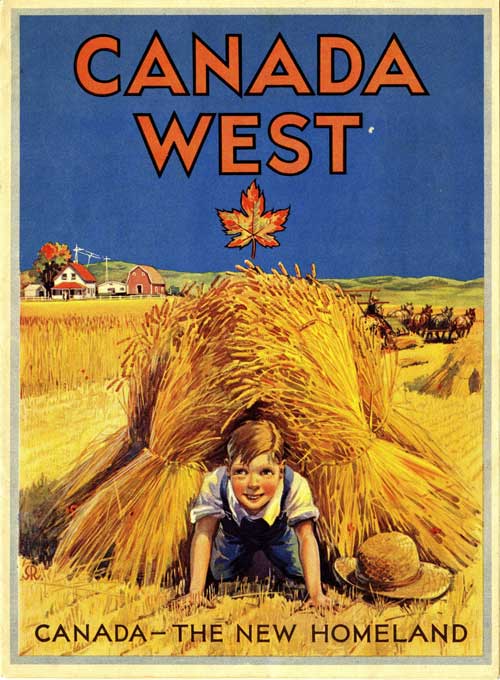

Did the government act on his report?

They sure did! Politicians were very eager for settlement to occur in the southern prairies as they were concerned about American expansion into Canada. They also wanted the wealth that would be created if farmers were to grow crops for export. So the Canadian Government launched an advertising campaign to encourage mostly European immigrants to settle the prairies.

Image: The Canadian Government tried to lure European settlers to the prairies with posters such as this one.

What in your opinion has been Macoun’s legacy?

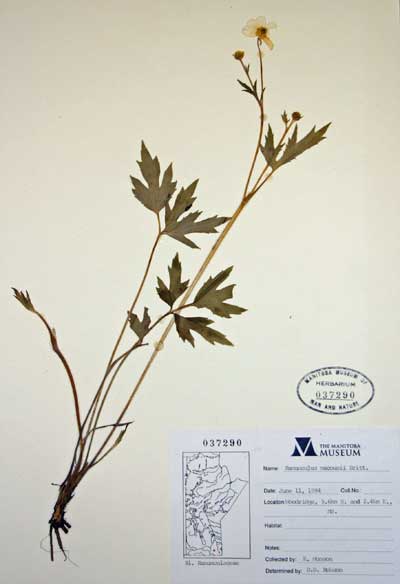

In his lifetime, Macoun collected over 100,000 plant specimens for Museum collections and about 48 species were named after him including Macoun’s Buttercup (Ranunculus macounii) and Macoun’s Gentian (Gentianopsis macounii). His prediction that the prairies would become the breadbasket of Canada was also true and prairie people are proud of that achievement.

But the flip side is that less than 20% of the original mixed grass prairie, less than 5% of the fescue prairie and less than half a percent of the tall grass prairie still remains in Canada. The prairies have more endangered species than just about any other ecological region in the country. In fact, I study endangered prairie plants and try to prevent them from going extinct in part because of John. So as a prairie lover I have mixed feelings about him. On the one hand I respect him for his scientific achievements but on the other, if he hadn’t been quite so enthusiastic about the agricultural potential of the prairies, perhaps there would be more of it left today.

Image: This buttercup species was named after John: Macoun’s Buttercup (Ranunculus macounii). TMM-B-37290.