Posted on: Monday September 28, 2015

As the opening of the National Geographic Presents: Earth Explorers exhibit at the Museum draws near, I find myself remembering some of the botanical explorers I learned about when I was a student. Although these botanists lived at different points in time they shared one thing: an insane passion for plants that very nearly caused their demise!

Sir Joseph Banks, 1743-1820

After whetting his appetite for botanizing in Newfoundland and Labrador, Banks manipulated his way onto the Endeavour, a ship captained by none other than James Cook. During this voyage Banks collected plants from South America, Australia, and New Zealand, contracted malaria, nearly died from exposure and lost four companions. While planning a second journey to search for Antarctica, Banks insisted on bringing 15 companions with him including two horn players (cause everyone knows you just can’t botanize without horn players following you around). To accommodate them, he had a second deck built on the ship Resolution, which made it too top heavy to be seaworthy. Captain Cook was not amused and had it torn down. When Banks saw that his new deck was gone, he had an “epic” tantrum worthy of a spoiled two year old and refused to sail, going on a trip to Iceland instead!

Image: Image of Sir Joseph Banks. V0000331 Sir Joseph Banks. Line engraving. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org Sir Joseph Banks.

David Douglas, 1799-1834

This irascible Scot was a true botanical nutcase. The son of a stonemason, Mr. Douglas became friends with renowned botanist William Hooker, who sent him on a plant collecting trip to the United States in 1823. Instead of bringing food, Douglas had his horse carry 100 pounds of paper to press plants in instead. This turned out to be a bad idea; he was reduced to eating all the berries, roots, and seeds he had collected on several occasions and was twice “obliged to eat up his horse” so that he wouldn’t starve to death. He nearly died from hypothermia, infections, falling into a gully, being attacked by grizzly bears, and the list goes on. The magnificent and enormous Douglas-fir trees (Pseudotsuga menziesii) of the west coast were named after him. He fell into a pit and was gored to death by the bull that was inside it at the age of 35.

Image: Cones of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) from the Museum’s collection. a species named after David Douglas. TMM B-C-3.

Benedict Roezl, 1823-1885

This hearty Czech botanist was obsessed with collecting orchids, discovering 8oo new species from the Americas. He was so obsessed with orchids that he once climbed a 5,000-m high mountain in Peru looking for new species, despite the fact that he had only one arm (the other was a prosthetic with an iron hook on the tip). To thwart competing orchid hunters, Roezl would either collect or destroy the rarest species he found, to the chagrin of conservationists everywhere. He was robbed by bandits 17 times but fortunately never lost much because the only things he carried were plants. Disappointed at the prospect of no money, one group of exasperated thieves was inclined to cut his throat. They spared him because he was clearly crazy (why would a one armed man wander around the countryside collecting weeds?), and believed that it was bad luck to kill a crazy person.

Image: Obsessed orchid hunter Benedict Roezl discovered this orchid, Miltoniopsis roezlii which was subsequently named after him. Image from plate 6085 in Curtis’s Bot. Magazine (Orchidaceae), vol. 100, (1874).

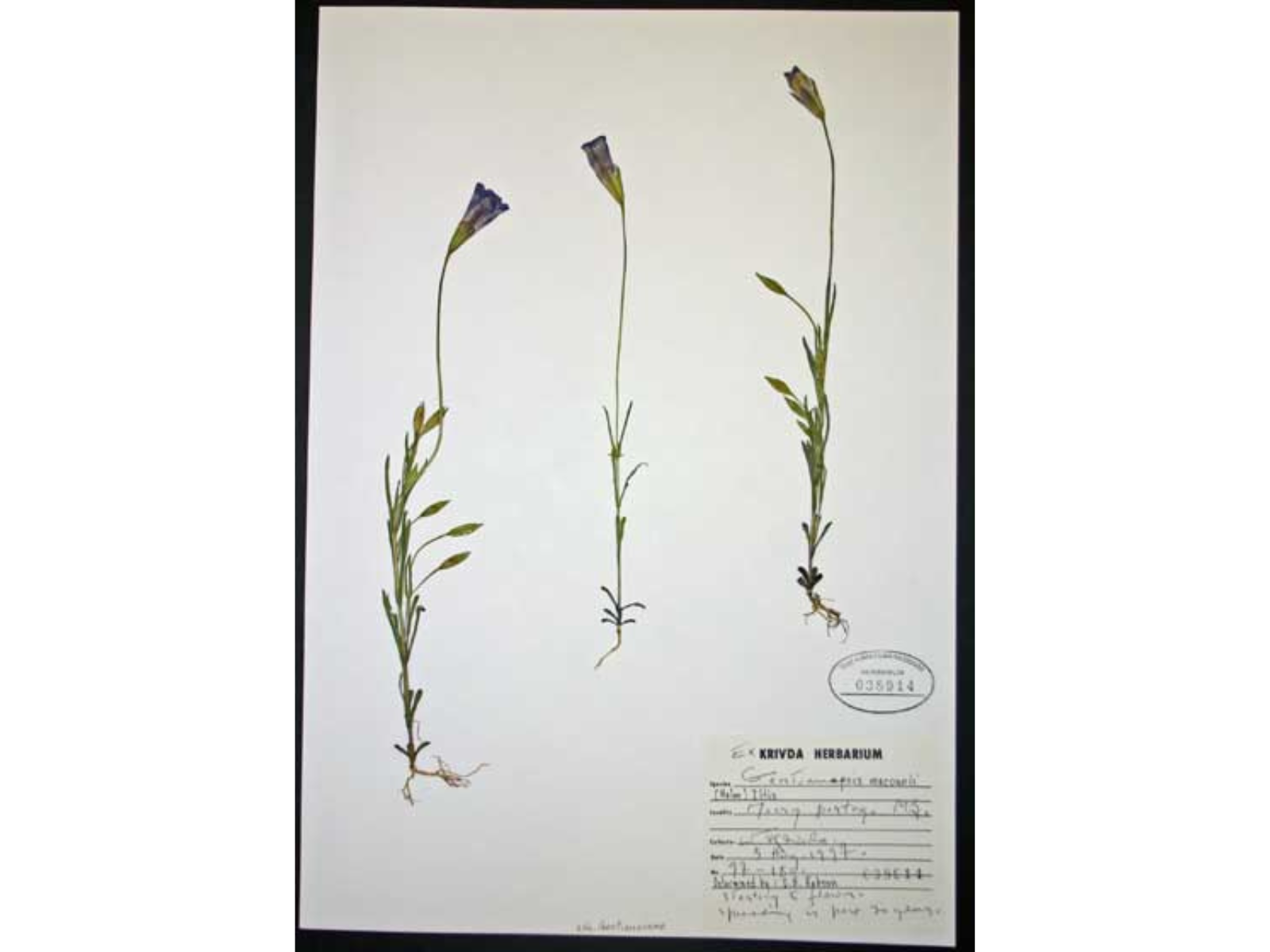

John Macoun, 1831-1920

Offered the chance to explore the wild west of Canada during a railroad route reconnaissance, Mr. Macoun jumped at the chance, despite the fact that he didn’t know how to swim, canoe, snowshoe, drive a dog sleigh, or even ride a horse very well. He left a pregnant wife and four children behind during his first trip from Ottawa to Victoria in 1872. His journeys to collect the west’s flora occasionally met with disaster. He nearly drowned, was almost crushed by two falling trees, and accidentally shot off his thumb. During one journey, too weak from lack of food to row his canoe upstream, he tied a rope around his waist so he could pull it while stumbling along the shore instead. He collapsed from exhaustion close enough to his destination that he was rescued by local First Nations people. Despite these hardships Macoun collected an astounding 100,000 plant specimens in his lifetime.

Image: Macoun’s Gentian (Gentianopsis macounii) was named after the obsessive Irish-Canadian plant collector John Macoun. TMM B-38914.

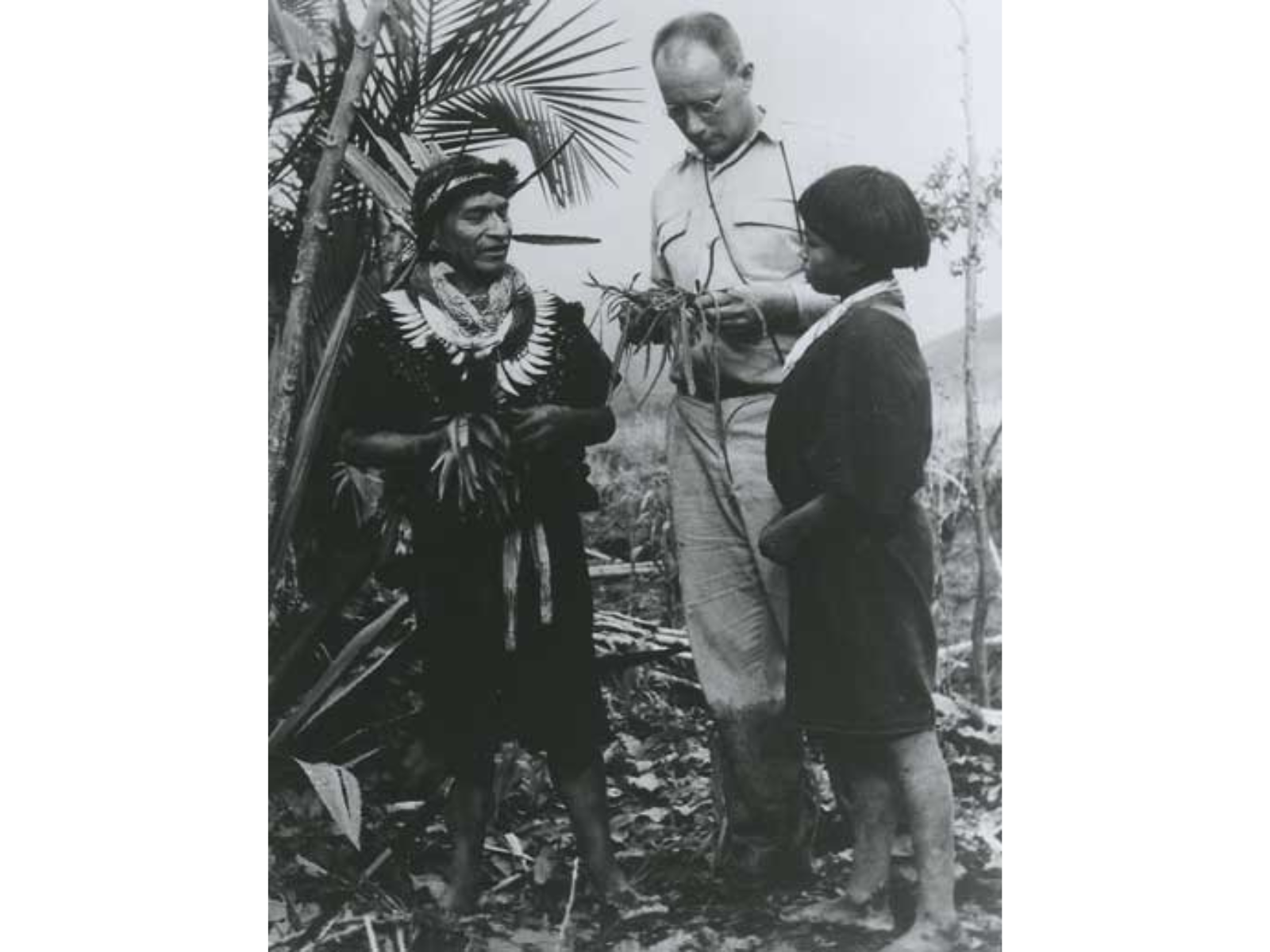

Richard Evans Schultes, 1915-2001

Schultes was obsessed with plants in a slightly different way than the others; he studied the medicinal and hallucinogenic ones. He wrote his undergraduate thesis on peyote and his Ph.D. on magic mushrooms. Not one to take someone’s word on the effects of hallucinogenic plants, he tried many himself, one time passing out for three days. He also took up the indigenous habit of chewing coca leaves to stay alert while travelling in the rainforests of South America. Once, he accidentally set fire to his collection while desperately trying to dry his plants in the jungle, nearly burning down his hosts’ house in the process. Schultes almost died from malaria, the nutritional disorder beriberi, and nearly drowned while doing field work. One night five vampire bats sat on his head and drank his blood. A grateful entomologist he once travelled with named a cockroach genus after him (Shultesia). He collected over 24,000 plants including 300 new to science and is considered the father of ethnobotany.

Image: Dr. Richard Evan Schultes in the Amazon. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Martin Dugard’s book “Farther Than Any Man”, Tyler Whittle’s “The Plant Hunters”, John Macoun’s autobiography “John Macoun: Canadian Explorer and Naturalist” and Wade Davis’ book “One River” were essential references for this blog and make excellent reading for those of you who wish to learn more about these extraordinary men.