Posted on: Wednesday October 19, 2016

Guest blog by Rachel Erickson, Assistant Curator

For the past four months, I’ve been working at the Manitoba Museum on a project about contemporary migration, just one part of the large capital renewal project Bringing Our Stories Forward. My project involves researching all aspects of migration to Manitoba; why do people come to Manitoba, and from where, what sort of policies have existed over the years that encourage (or discourage) migration, how have people settled in, and what sort of challenges might they face upon arrival. One of the aims of the project is to collect oral histories about modern migration to Manitoba, and potentially collect new objects that can be added to the museum’s collection, in order to paint a more inclusive picture of the diverse communities that now live in the province.

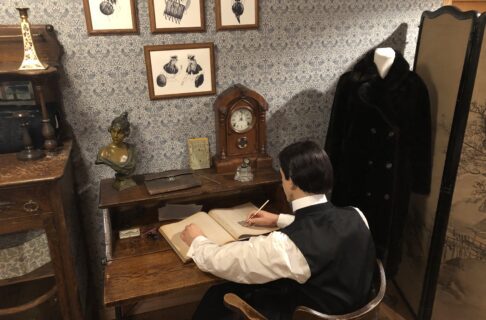

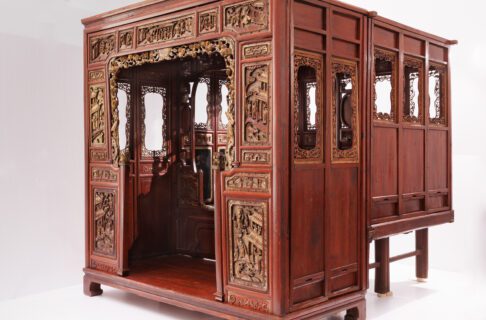

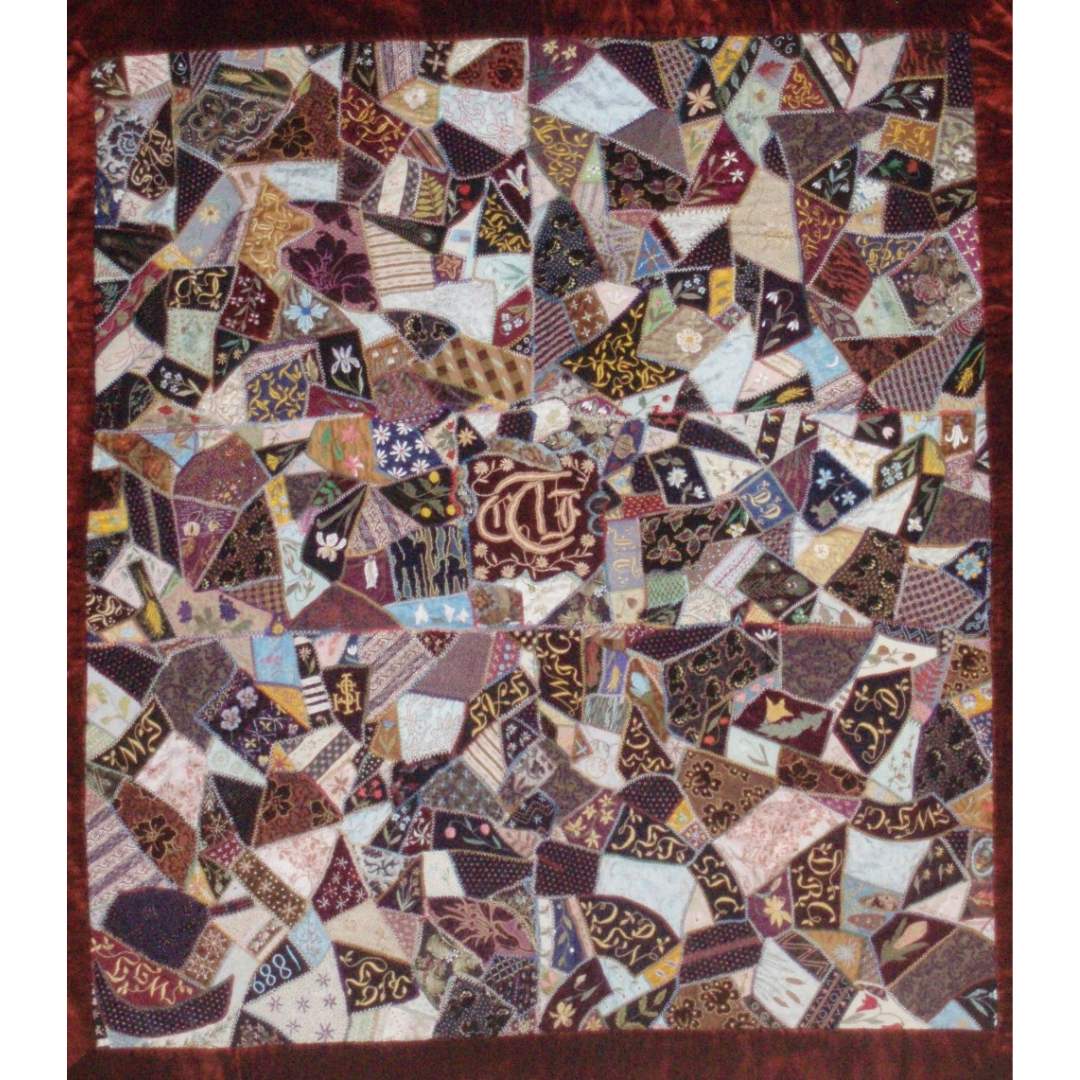

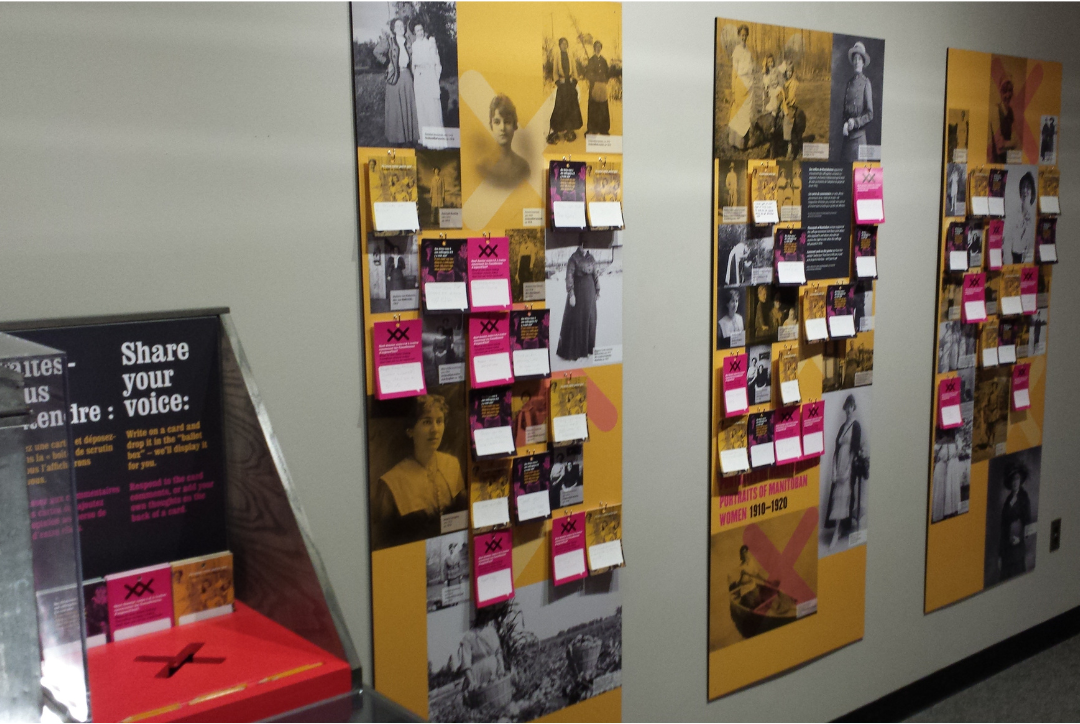

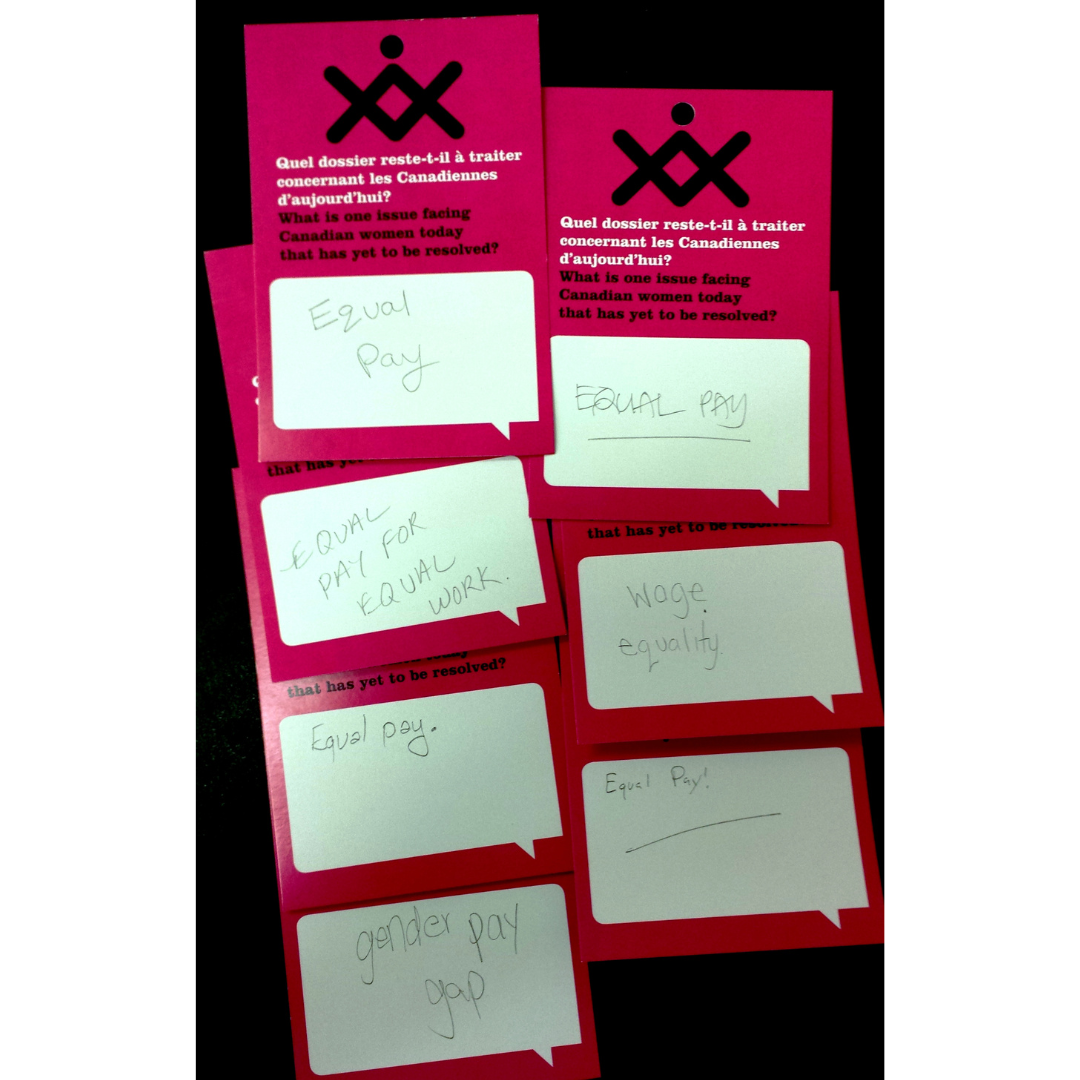

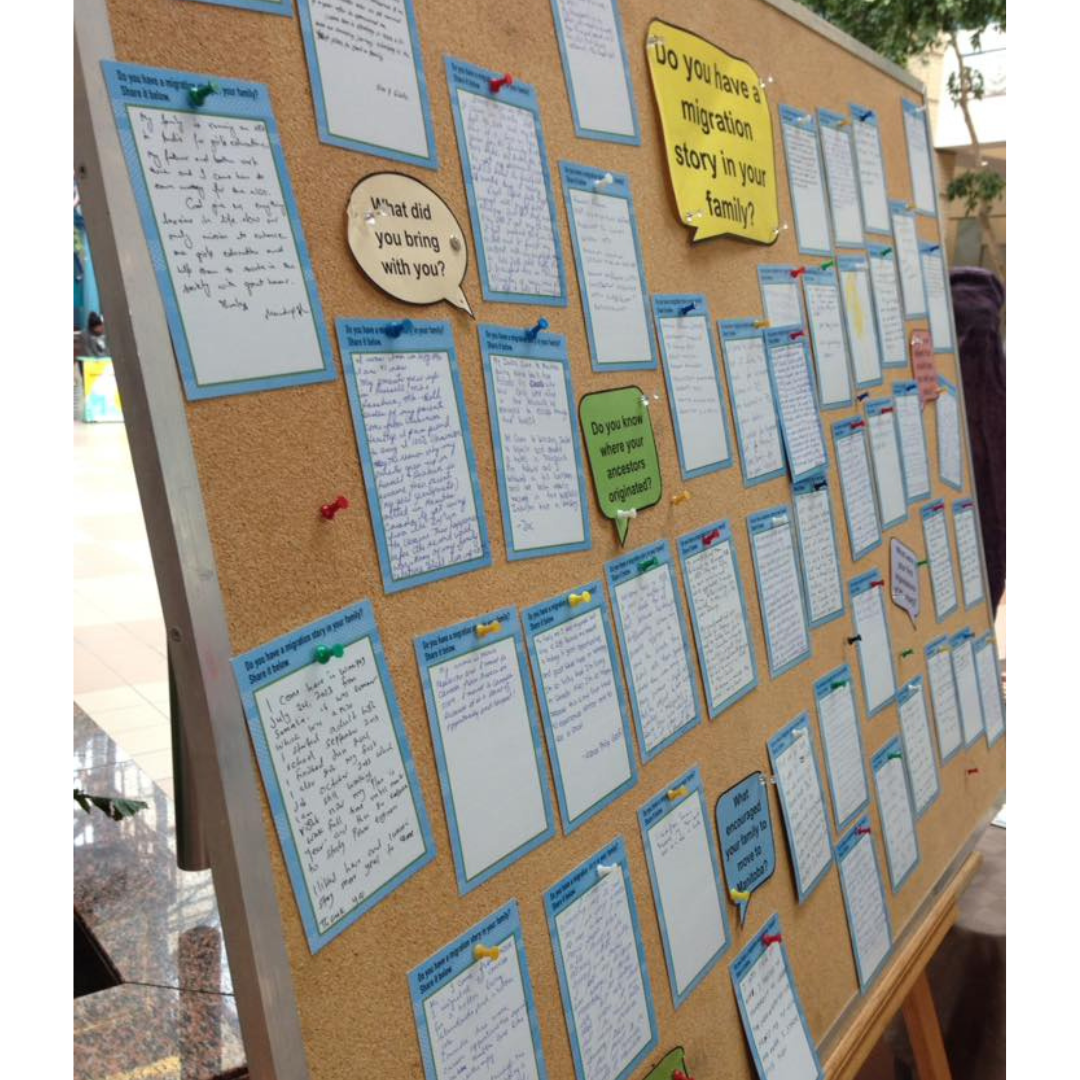

In August, I hosted a series of “pop-up museums” at three shopping centres in Winnipeg: Garden City, Polo Park, and Portage Place. I took out five museum objects (some with their own interesting migration histories), and set up a mini exhibition. We brought along an interactive activity that asked the public, “Do you have a migration story in your family?” and asked visitors to share stories about their decision to come to Manitoba, their journey here, and what it’s been like settling in.

A family tells their story at Garden City.

Story board at Portage Place.

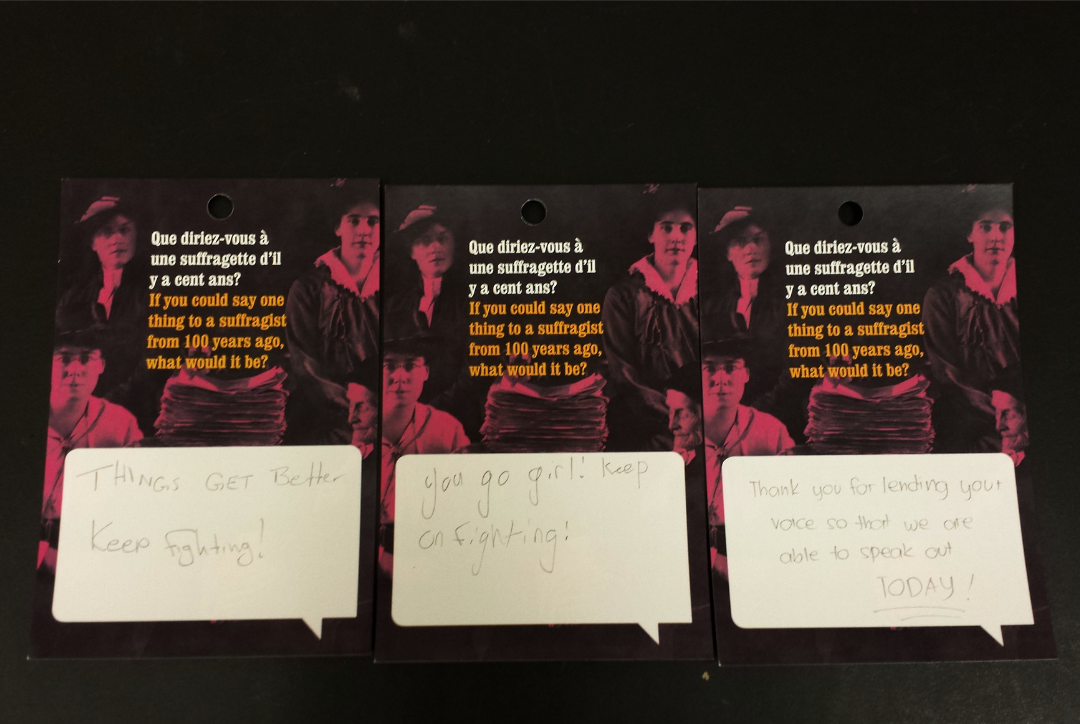

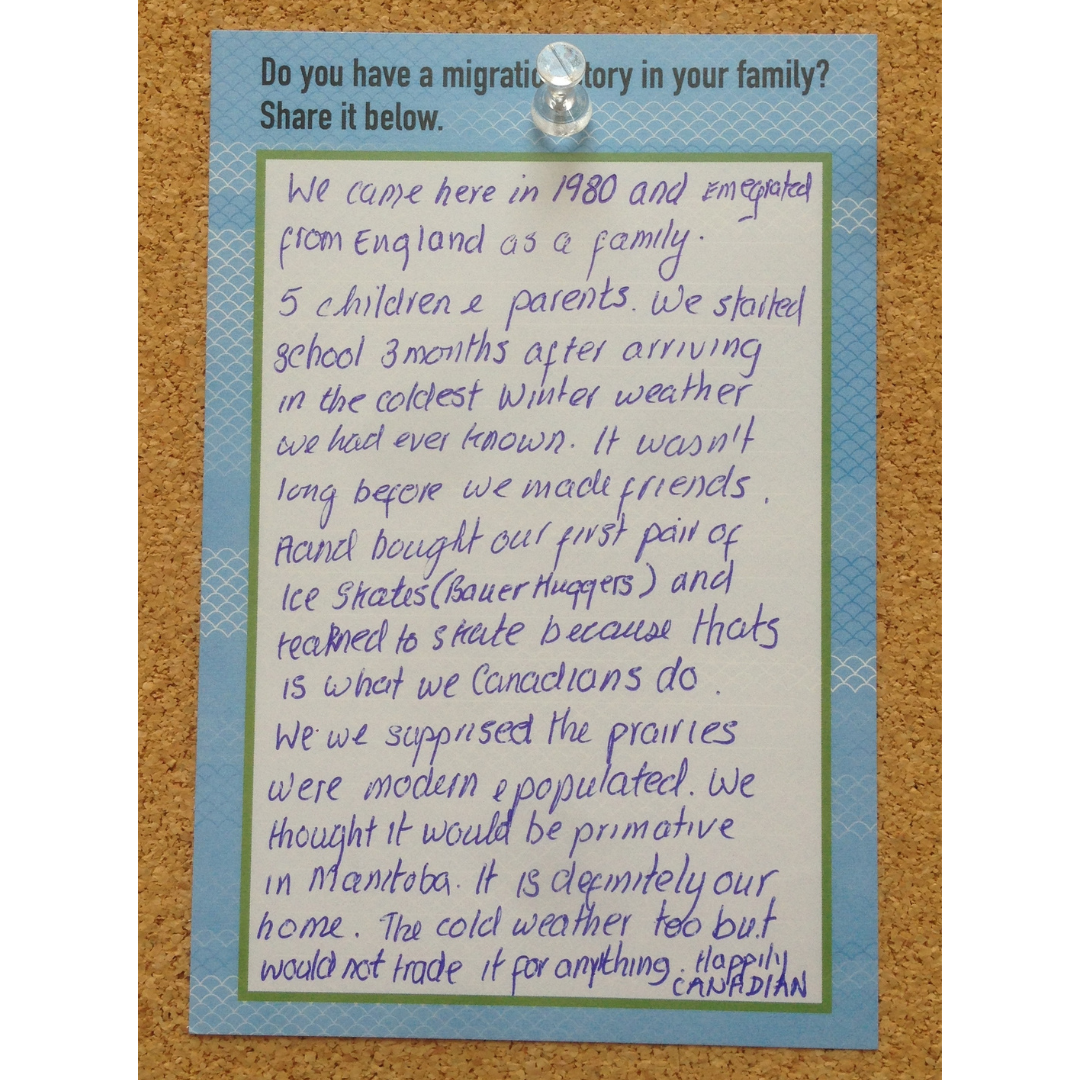

Over the course of a few days, we heard stories from all over the world – Somalia, India, England, Trinidad, Philippines, Nigeria, Kosovo, you name it! Unsurprisingly, a fair number of “winter arrivals” expressed their horror at the cold weather and the copious amount of snow. One of these new arrivals found that learning to skate was the most effective Canadian initiation.

There are many reasons why people leave home – some move for a job, or the hope of better opportunity, others move for university and then decide to settle, some are uprooted by war or political strife, others find love, or move to be closer to family. No matter the reason for movement, the people we spoke with all had fascinating stories to share about settling in, finding their way in a new place, and ultimately, feeling at home in Canada. I can’t wait to hear more.

If you have a migration story that you’d like to share with the museum, please get in touch! You can contact Rachel Erickson at the museum at 204-988-0685.

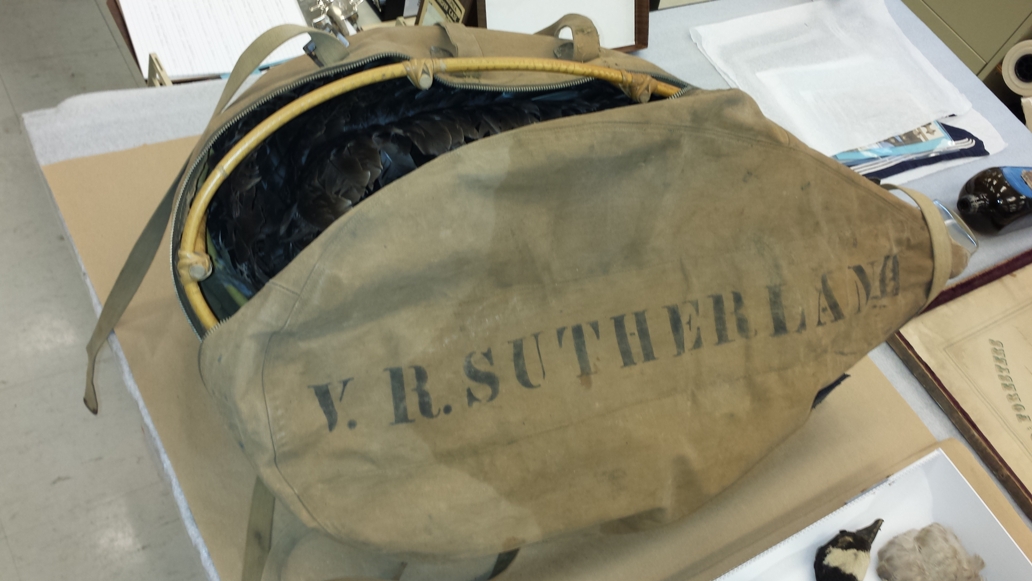

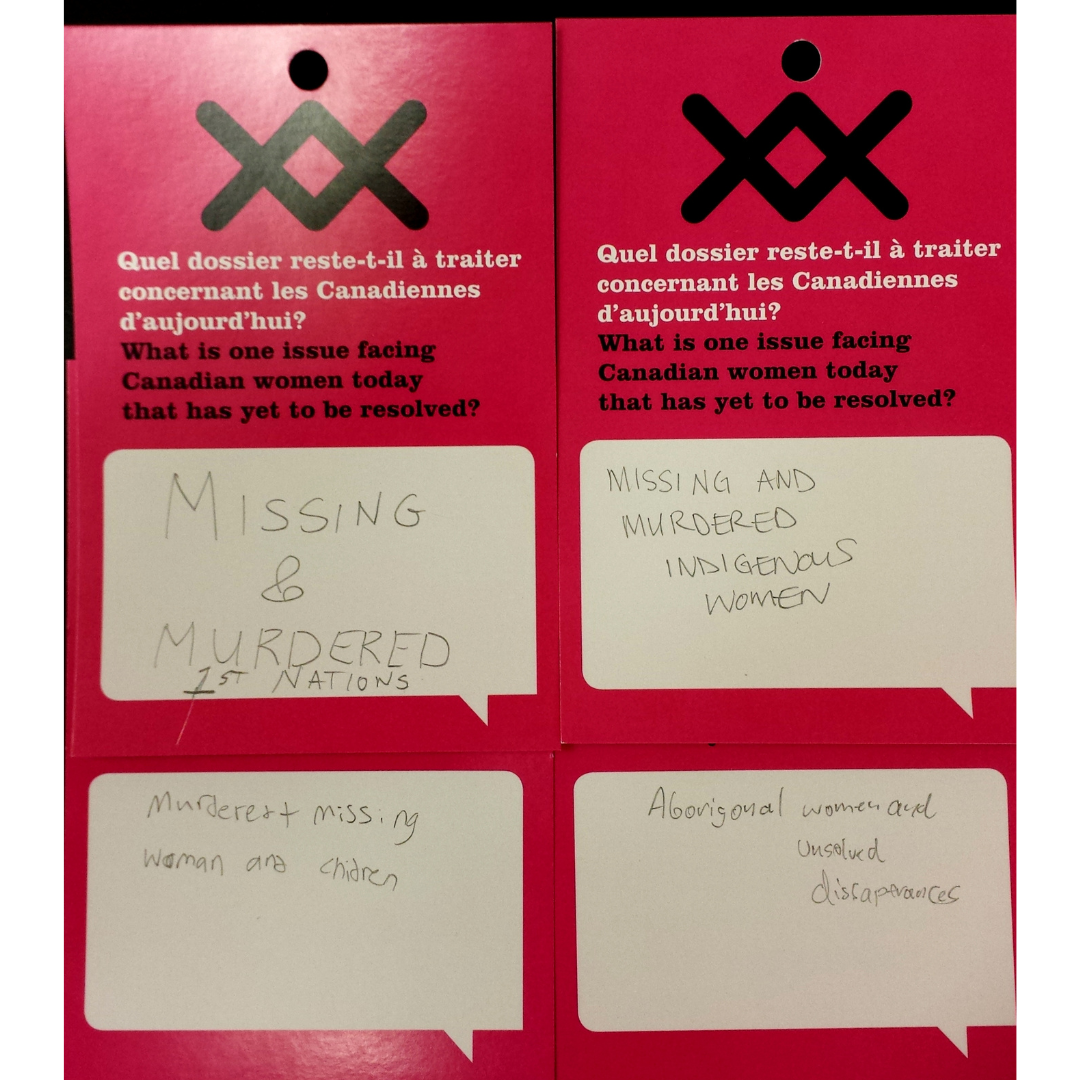

Image: A story by a woman from England who moved to Manitoba in 1980.