Posted on: Monday February 1, 2016

With Valentine’s Day just around the corner, flower sales are set to soar. Men give flowers to women to increase the chances that they’ll get some lovin’ but they don’t typically think about the fact that in doing so they’ve already helped something reproduce-namely the plant. Flowers are the sexual organs of plants and their methods of reproduction are both fascinating and bizarre. However, plants can be complicated so to make this easier to understand, I’m going to describe how people would have babies if we were like plants.

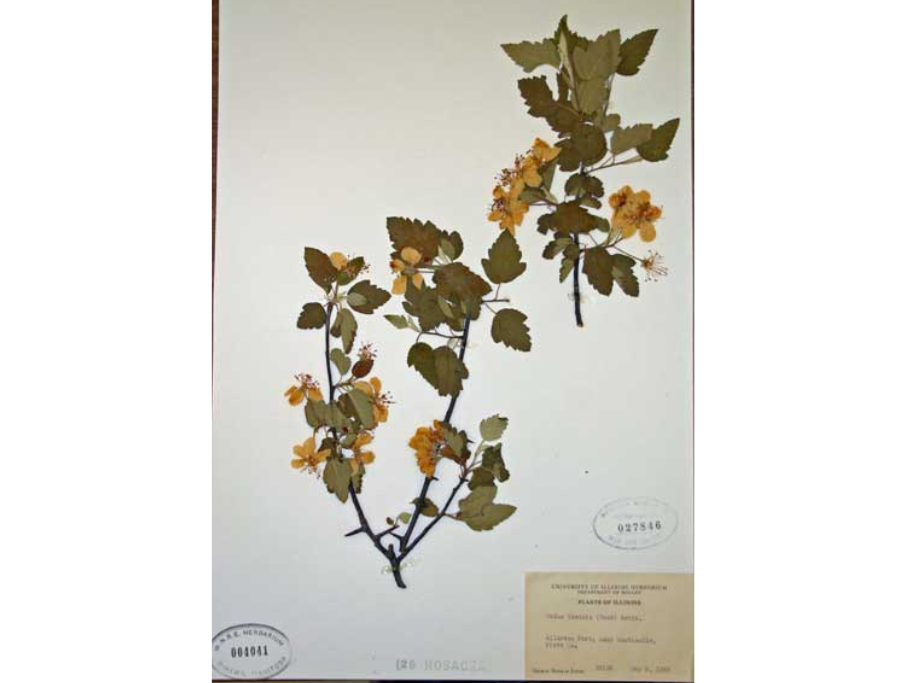

If people were like plants most of us would be hermaphrodites (both male and female). Very few plant species have separate males and females; buffalograss (Buchloe dactyloides) is one of the only ones in Manitoba. Most plants (~90%) have both male (stamens) and female (pistils) organs either on the same flower or the same plant. Hermaphroditic plants are either receptive to receiving pollen or actively releasing pollen but not usually doing both at the same time to prevent inbreeding. Some plant species can even switch from being male to female part way through their lives.

Image: Buffalograss (Buchloe dactyloides) is one of the few Canadian species that has separate male and female plants.

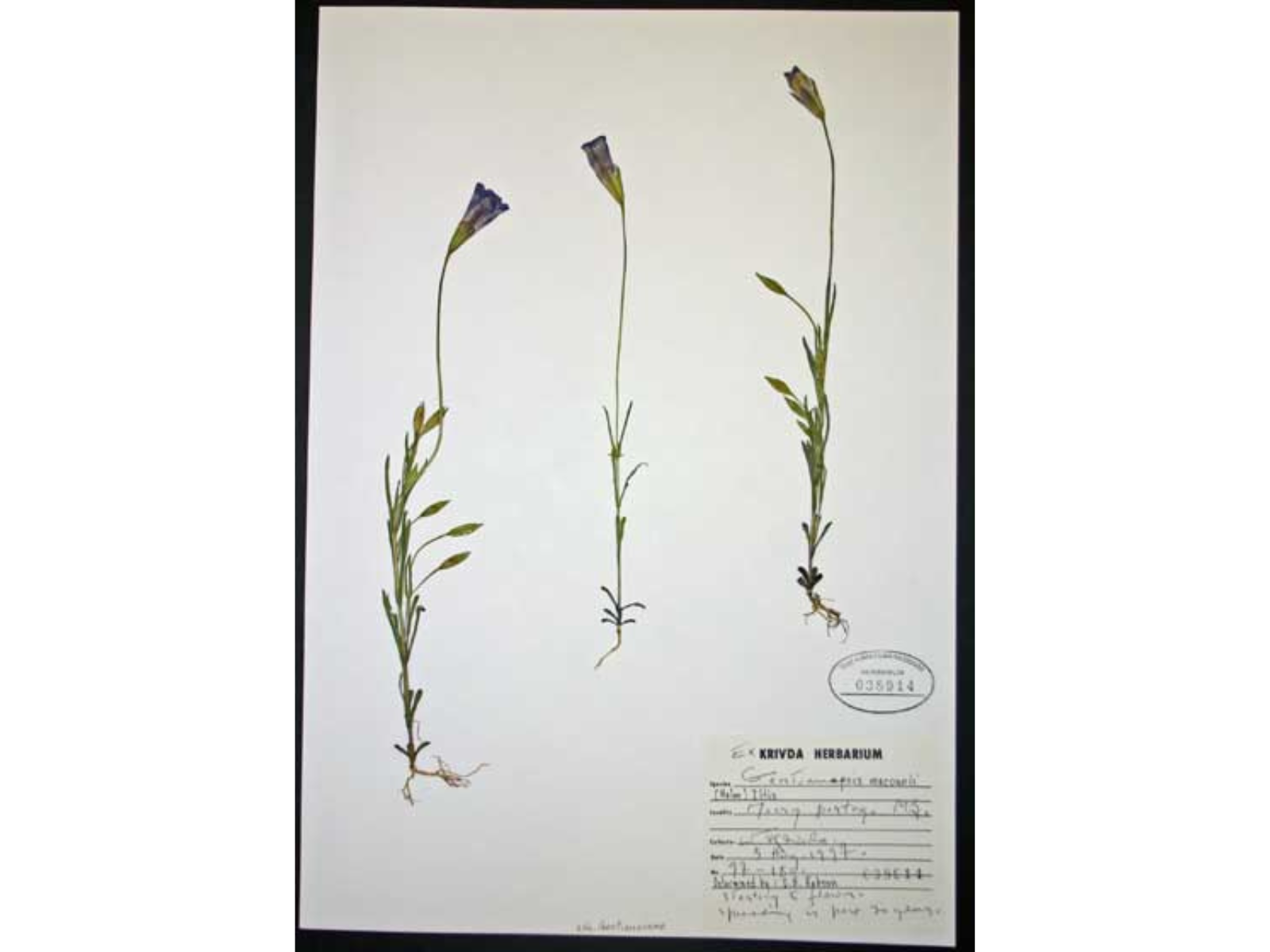

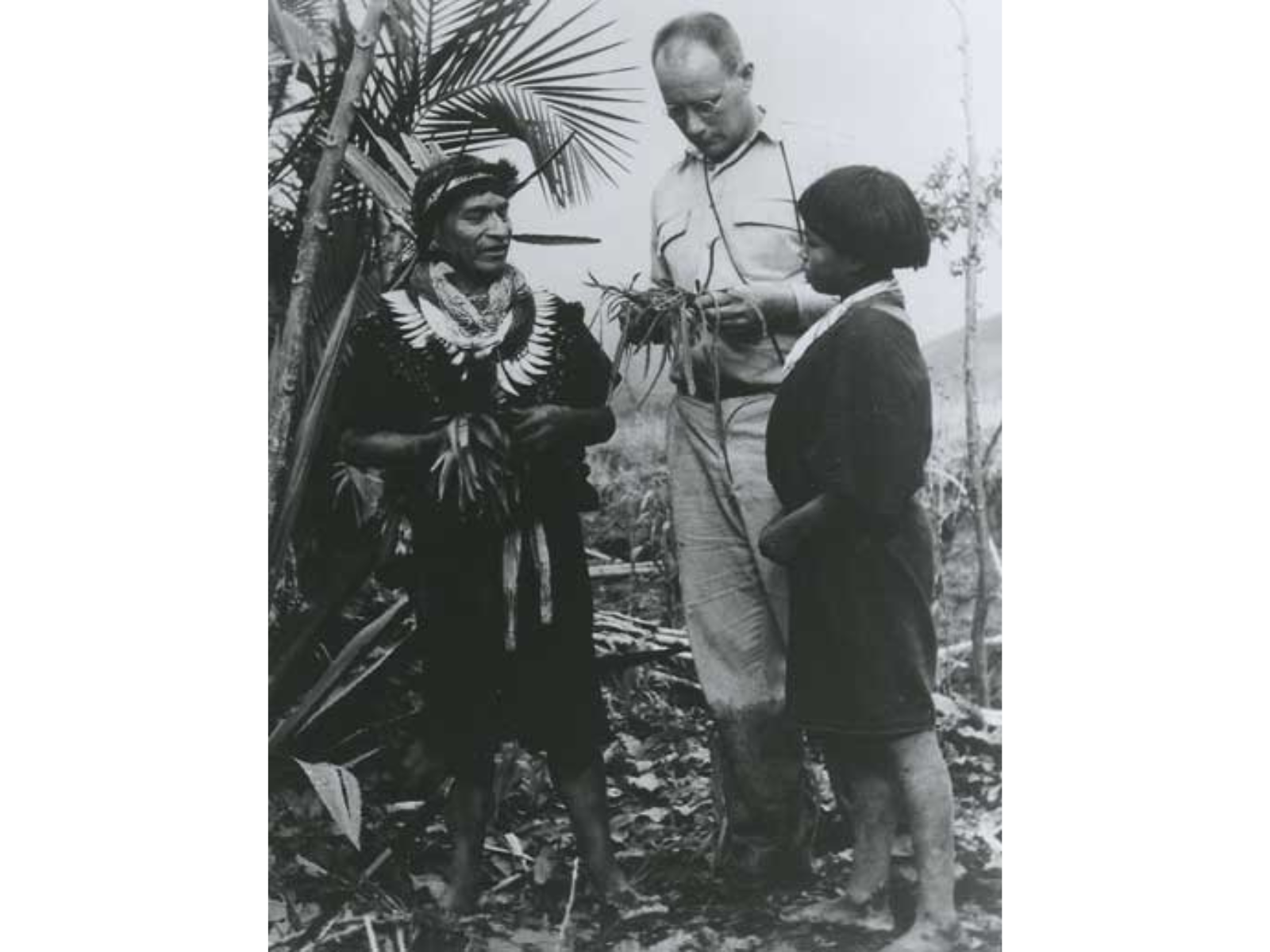

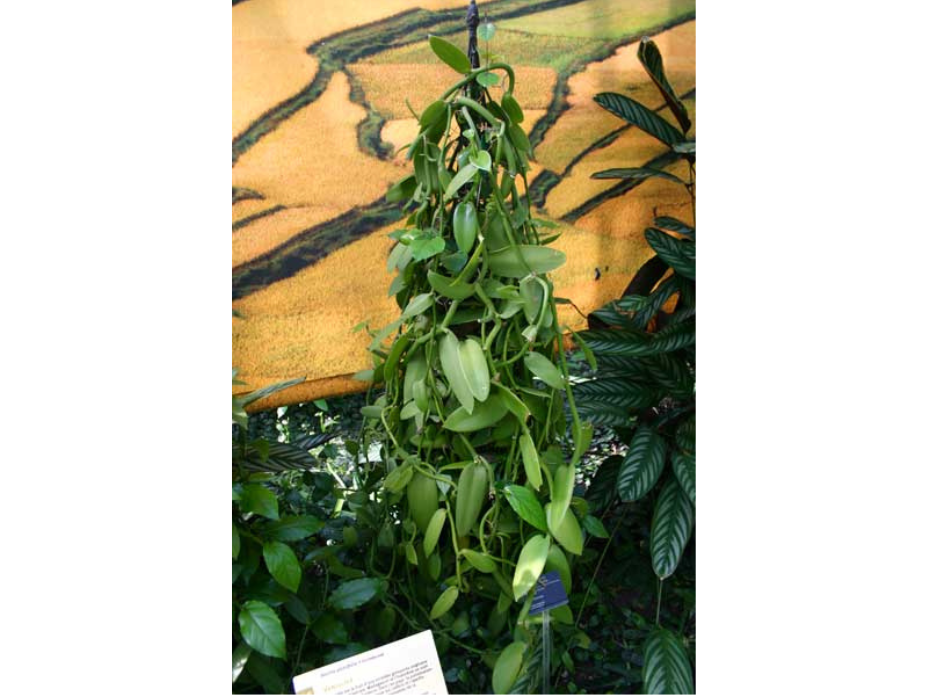

If people were like plants, in-vitro fertilization would be the norm. Most plants rely on a third party, such as an insect or bird, to help them reproduce. The animal removes pollen from the stamens of one flower and transfers it to the pistil of another flower. Humans also sometimes fill this role, hand pollinating crop plants like vanilla (Vanilla planifolia) when insect pollinators are not available.

If you couldn’t find a mate and really wanted to have a baby, you could just fertilize yourself! The baby would be a clone that is genetically identical to the mother. Many plants can fertilize themselves in case they are not visited by pollinators. Self-fertilization isn’t ideal as inbreeding can produce individuals that are less healthy but at least all the effort spent producing eggs and pollen is not completely wasted.

Image: This bumblebee (Bombus) is fertilizing a breadroot (Pediomelum esculentum) plant. The bee gets paid with a delicious drink of nectar.

If you wanted a child but didn’t want to give birth, you could just grow a little doppelganger of yourself on your foot. Once the baby was big enough, it would fall off and start running around. Hooray! No 16-hour labour to go through! This type of reproduction (asexual) is quite common in perennial plants. Some plants produce bulbs or tubers which eventually break away from their parents, forming separate but genetically identical new plants. Other species, such as sod grasses and aspen (Populus) trees produce long underground stems from which new plants emerge. This strategy can be very successful if there is no suitable habitat for a seed to germinate in.

Image: Many lilies, such as this prairie lily (Lilium philadelphicum) reproduce asexually by creating bulbs.

If people were like plants everyone would have several thousand children every year. Unfortunately, about half of them would be eaten by lions; seed predation is high in plants with 40-50% losses to birds, rodents, and insects being common. The seeds that do survive might spend decades living in a vegetative state before resuming a normal life and reproducing; this is sort of like having teenager who does nothing but play video games all day. The oldest seed ever successfully grown was a Judean date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) that was about 2,000 years old. Talk about a failure to launch!

So when you’re purchasing or appreciating your Valentine’s Day flowers this year remember that at the very least, the plant has gotten lucky!