Posted on: Wednesday August 14, 2013

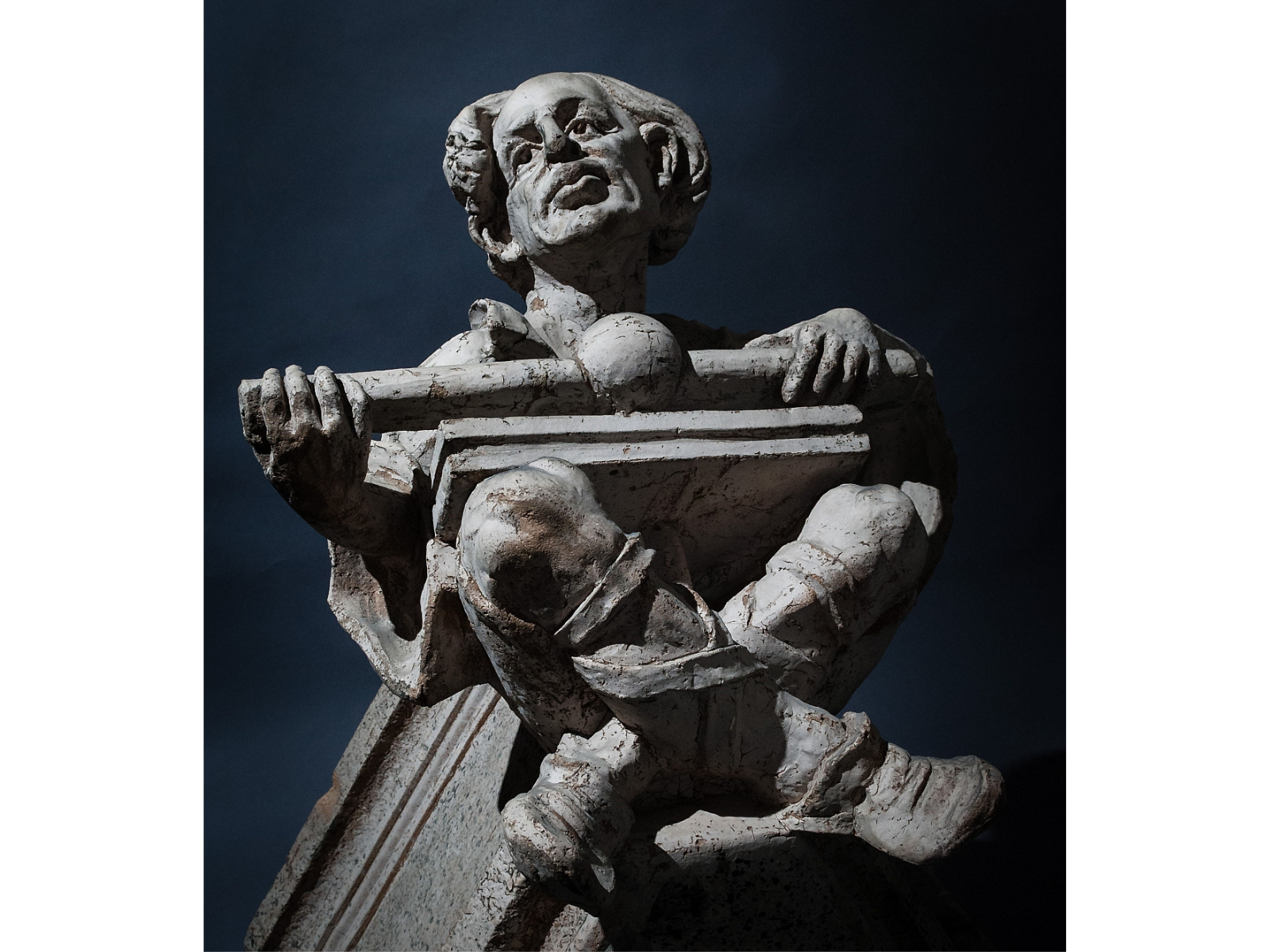

Some time ago, after the donation of a “gargoyle” that once graced the former Winnipeg Tribune Building, we put out a call to the public to see if any more of these strange terra cotta statues would show up (see my blog of March 30, 2012). Fourteen are known to have existed, and The Manitoba Museum had two. We did get some calls, with two leads to something I had not expected: giant grotesque heads that adorned the exterior of the building at the top of the first storey – (the gargoyles were soaring at 6 storeys). I checked out the original architectural plans at the Archives of Manitoba, and it turns out there were fourteen of these heads as well!

It’s believed that this head might represent a newspaper boy.

Image: Terra cotta “grotesque” from the Winnipeg Tribune Building, 1913.

I also mentioned in my previous blog that I was trying to identify the original artist. Well, I found out that all the grotesques were made at the American Terra Cotta and Ceramic Company factory near Chicago, Illinois. The artist may have been Kristian E. Schneider, a Norwegian immigrant who worked with American Terra Cotta from about 1906 to 1930. He was their lead sculptor and modeller and had early in his career worked very closely with Louis Sullivan, the famous architect of the “Chicago School”. Sullivan was instrumental in the development of the steel beam skyscraper, and his work also influenced the architect of the Winnipeg Tribune Building, John D.Atchison, who commissioned the grotesques. It seems that for a brief time at least, Winnipeg really was a Chicago of the North.