Posted on: Friday February 24, 2017

When Manitoba became part of Canada in 1870 the stage was set for one of the largest land transformations in history. In the last 150 years nearly all of Manitoba’s wild prairies fell to the plough. The little patches that remain as ranch land, private nature preserves, and federal and provincial crown lands are home to a suite of increasingly rare organisms, among them two spectacular prairie orchids: Western Prairie Fringed Orchid (Platanthera praeclara) and Small White Lady’s-slipper (Cypripedium candidum). Models of these two species are on display in the Manitoba Museums’ Legacies of Confederation: A New Look at Manitoba History exhibit.

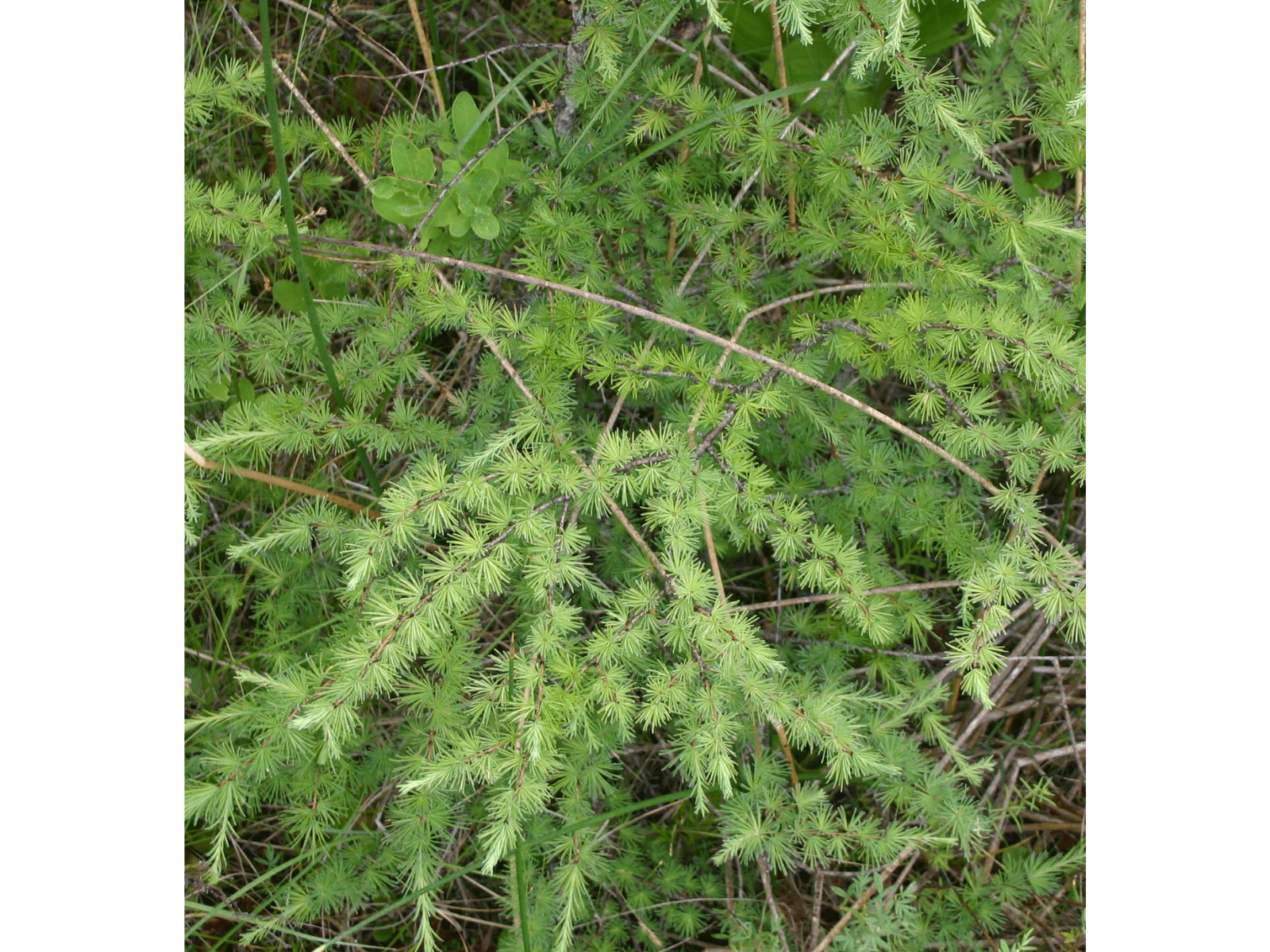

Found only in moist, tall grass prairies with calcium-rich or alkaline soils, the Western Prairie Fringed Orchid is one of Canada’s legally protected endangered species. The only place where it is found in Canada is at the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve near Gardenton (click here for more details). Standing at almost a metre tall, this orchid produces an intoxicating fragrance to attract pollinating sphinx moths at night. The Canadian population is the largest in the world so its survival largely depends on our willingness to protect it.

Image: The endangered Western Prairie Fringed Orchid’s largest population is in Manitoba.

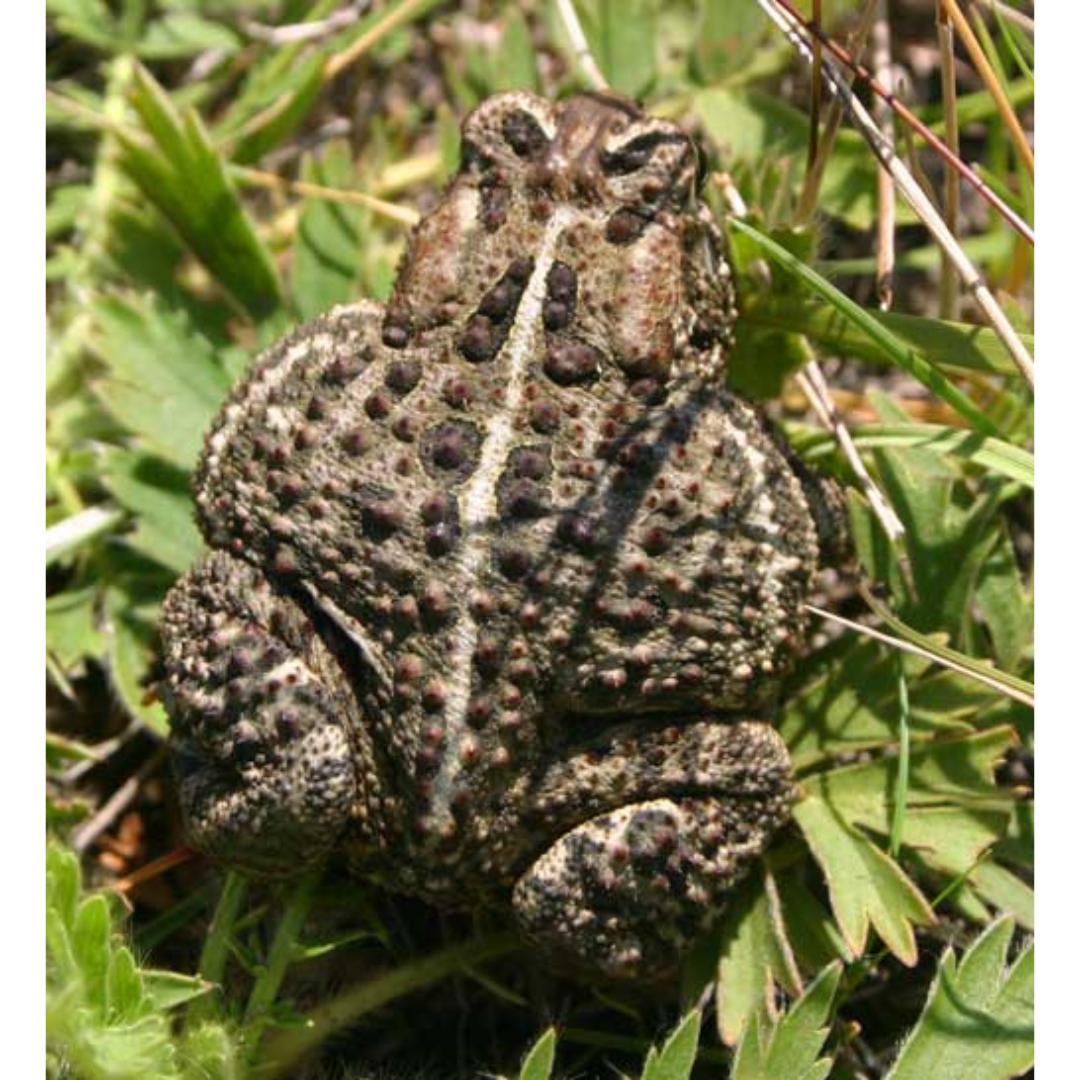

Manitoba’s other endangered orchid, the Small White Lady’s-slipper, is a bit more widespread. It occurs at the Tall Grass Prairie Preserve but there are also populations further west, near Brandon, and further north, close to Lake Manitoba. It is a bit more common in the USA but still rare over most of its range. It prefers moist prairies with calcium-rich soils. The Small White Lady’s-slipper attracts small bees in the spring with its delicate scent but does not offer a nectar reward so pollination is infrequent.

Image: The Small White Lady’s-slipper is an endangered species in Manitoba and Canada.

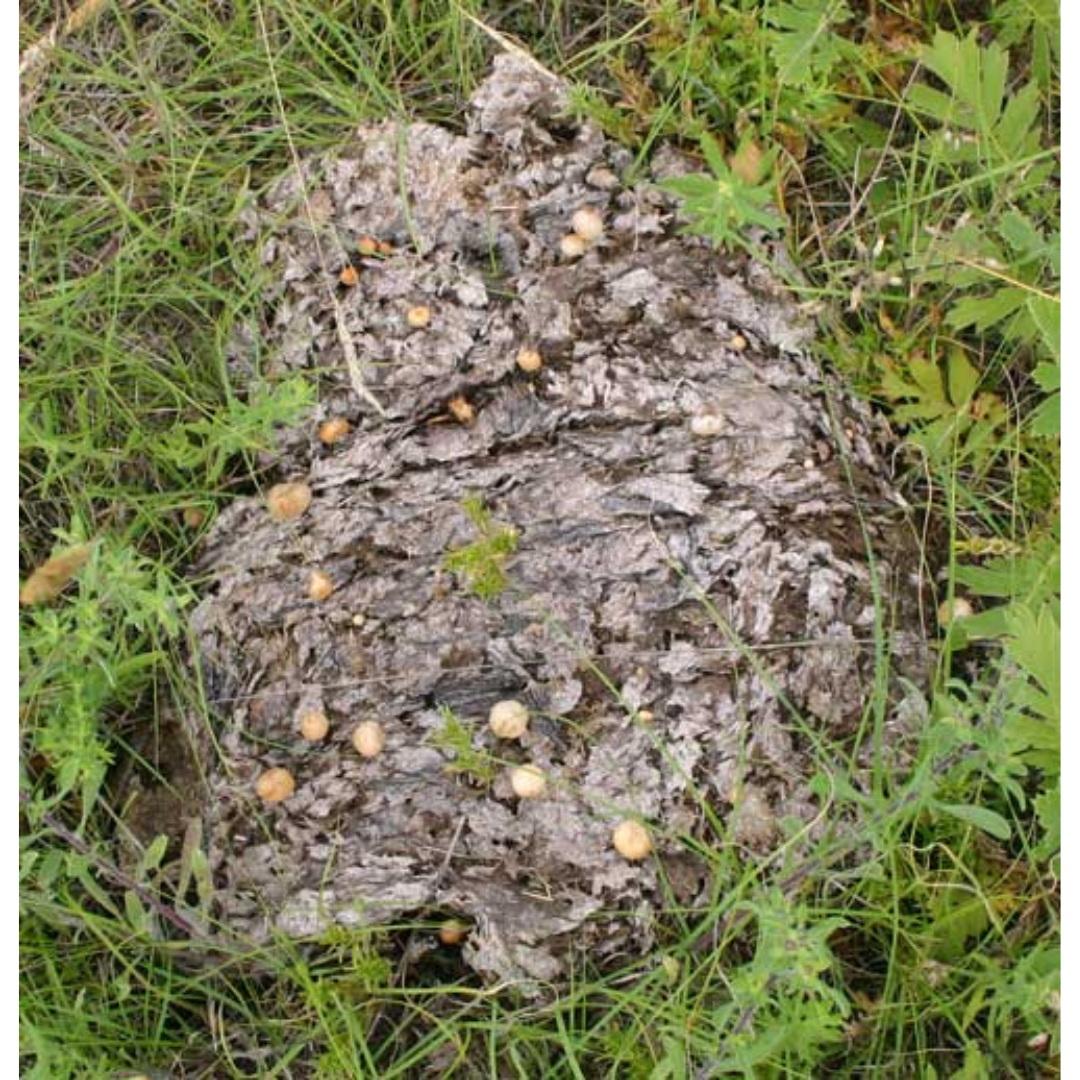

In addition to their very specific habitat requirements these orchids produce seeds that are so tiny that there is virtually no nutrition available for young seedlings. In order to grow they need to form an association with a special fungus, called a mycorrhiza, which will help them get water and nutrients from the soil. The dependence of these two orchids on insect pollinators and soil fungus, along with the loss of habitat, has led to their endangerment.

It’s hard to believe that there was a time when people thought that species extinction was impossible. Humanity underestimated the power that our technology gave us over nature, and to some degree we still do. A conservation ethic did not really emerge until it was clear that there were no “lost worlds” left where rare species might still linger. The extinction of several Canadian bird species including the Labrador Duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius), Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis) and Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), largely due to overhunting, finally made Canadians understand our destructive capabilities and helped inspire the modern wildlife conservation movement. One of the benefits of confederation has been our collective will to ensure that some of Canada’s forests, tundra, prairies, lakes and ocean habitats are protected for all Canadians to benefit from–the 2-legged and the 4-legged and even the ones with no legs at all.