Posted on: Tuesday July 30, 2024

Sometimes objects come in to the Archaeology lab that aren’t really artifacts, but are still interesting in their own right. This happened this past spring when volunteers in the Archaeology department came across some curious objects while processing artifacts. I had asked them to go through a donation made by the Criddle family, and among the arrowheads and scrapers were two weird little blobs that none of us could figure out. Until recently, that is.

The Criddle family came to Manitoba in 1882, and they had a property near Wawanesa that was like a little piece of England on the Prairies. They donated a large collection to the Museum that included everything from photographs to furnishings. (The Museum has covered their collection several times in our social media.) It turns out that the donation included some archaeological artifacts that were collected almost incidentally. Like a lot of farming families, the Criddles picked up artifacts and other objects that they came across in their fields, and these eventually made their way to the Archaeology lab.

Volunteering at the Archaeology Lab

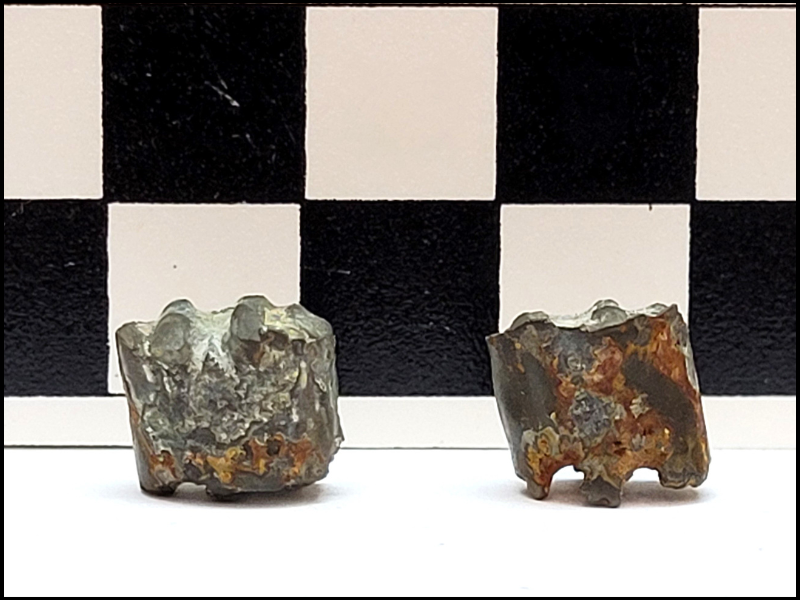

The students volunteering in my lab are just learning about Manitoba archaeology. They’re fast learners, and they are getting a sense of how to sort cigar boxes full of bric-a-brac into organized piles of ancient tools, bone and shell, and so forth. In this collection they found two irregular cylinders of what looked like stony or metallic material. These were non-magnetic, so at first we thought they might be lead scrap or maybe furnace slag. That didn’t explain their irregular-but-oddly-identical appearances. They looked like they might fit together, but fit together into what?

Two mysterious objects found in the Criddle collection.

The objects almost look like they had little legs…

Let’s jump ahead in time a bit. A few weeks ago, Museum staff were working with our new pXRF instrument. That bit of alphabet soup stands for portable X-ray fluorescence, which is a non-destructive technique to determine which elements are in an object. The instrument emits X-rays which contact the target object and then create secondary x-rays, the frequencies of which can be matched to the elements present. The Museum is using our pXRF instrument for research in all of our departments and also to analyze objects under conservation. (We can also do analysis for other researchers for a fee.)

The results came back: a lot of iron, a bit of sulfur… and no lead. We scratched our heads and then it dawned on us that looked a lot like pyrite. Joe Moysiuk, our Curator of Geology and Palaeontology, suggested that our blobs could be ancient shells that had been fossilized and replaced with pyrite. We took a closer look and the two pieces articulated, just like part of a shell. Joe took another look and suggested they might be from Baculites, a type of straight-shelled ammonite that went extinct around the same time as did the dinosaurs. Imagine a squid-like critter with a long, straight, segmented shell behind it.

Stories Written in Stone

Baculites segments (particularly the larger ones) are sometimes called “buffalo stones.” These figure in the stories of Indigenous peoples of the Plains, such as the Blackfoot who call them iniskim. The fossil segments have articulation points that look like heads and legs, and resemble little buffalo. As a result, they have a spiritual connection to the larger animals and were used to call them. I am unsure if something similar existed on the Manitoba plains but I suspect that it did. If anyone is willing to share old stories, please drop me a line.

I can’t say if these little fossils were collected or used by Indigenous people in southwestern Manitoba. They definitely stood out as something unusual and were picked up by the Criddles. For me, these are also ecofacts – objects found at archaeological sites that are not made by humans but still tell you things about the landscape. They opened my eyes to questions of palaeontology and ethnography that I otherwise might not have looked into.

Every field, and every object in that field, can tell a story.

A segment of a Baculites fossil from the Cretaceous era, collected near Brandon and now in the Museum’s Palaeolontology collection.