Posted on: Tuesday February 24, 2015

Scientists have spent many decades arguing with each other about lichens. It’s a plant! No, it’s a fungus! No, it’s an alga. It’s a fungus parasitizing an alga. No, it’s an alga parasitizing a fungus! Nobody’s parasitizing anybody! They’re living in harmony like a bunch of hippies in a commune! I prefer to think of a lichen as an organism with an identity crisis. No wait, that’s not very flattering. Perhaps they are more like legless organism support groups. Or maybe they’re akin to exclusive nightclubs with a “no animals allowed” sign on the door.

For a long time no one knew anything about the true nature of lichens. Back in the days before microscopes the only organisms that people could see were creatures that moved (animals) and creatures that didn’t move (plants). Fungi and lichens could not move and were thus considered “plants” albeit unusual ones as they were not green.

Eventually scientists began to realize that the natural world was much more complex than they could possibly have imagined. After microscopes were invented they realized that there were lots of “mini-organisms” and eventually a third Kingdom, the Protista, was proposed. However, it wasn’t until 1969 that Robert Whittaker’s five kingdom classification that considered “fungi” to be separate from plants, was published in the journal “Science”. When The Manitoba Museum opened in 1970, fungi were still broadly considered by the public to be “plants” as most biology textbooks did not incorporate the new five kingdom classification right away. This system of classification is still referred to in some of the Museum’s older galleries such as the “Lichens: The Good Partners” exhibit in the Arctic-Subarctic Gallery. A lack of funding for gallery renewal has prevented us from updating these old exhibits.

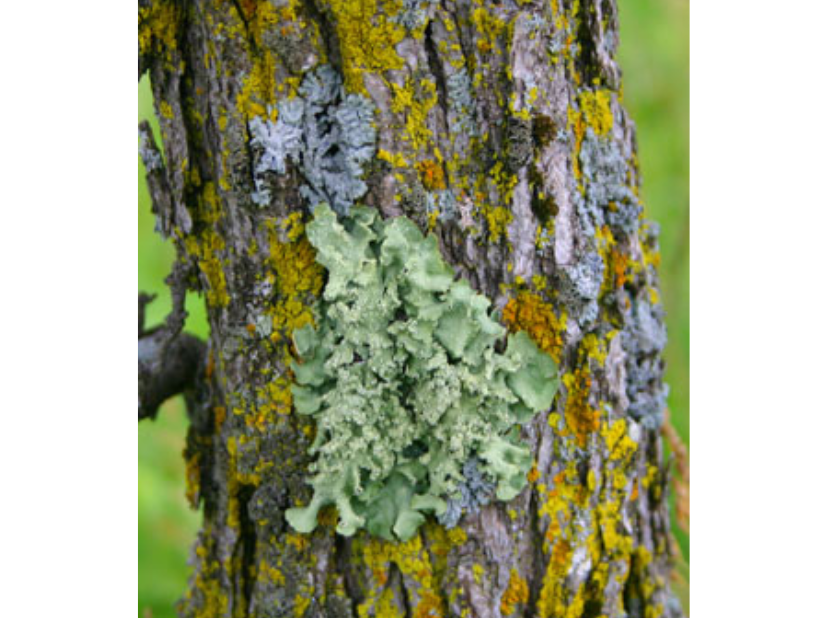

Image: Fungi were still considered to be primitive plants when the Museum first opened.

In reality, lichens cannot be classified as anything because they are composite organisms containing species from (probably) four different kingdoms. The scientific name of the lichen is based on the name for the fungal host (Kingdom Fungi) but lichens also contains photosynthetic organisms called “photobionts”. The photobiont is usually a green alga (Kingdom Plantae) but sometimes a golden or brown alga (Kingdom Chromista) or a cyanobacteria (Kingdom Bacteria). Some lichens, like the dog lichens (Peltigera spp.), have both green algae and cyanobacteria in them (it’s the party spot of the lichen world cause the cyanobacteria mix a mean nitrogen smoothie!). Some biologists even consider lichens as “self-contained mini-ecosystems”.

You’d think with our high powered microscopes, fancy computers, and DNA analysis that we would have this classification thing all worked out. But the more things change the more they stay the same, and scientists are still arguing about how we should classify the organisms on our planet. Whatever we decide call them, there’s one thing for certain-the lichens are completely indifferent to our puzzlement over their true nature.