Posted on: Tuesday August 2, 2011

While examining the backlog of uncatalogued plants in my lab I came across a very old and intriguing collection: 28 vascular plants from Ungava, Labrador collected in 1876 by a Mrs. Lizzie Crawford. Immediately my curiosity was aroused. Who was this mysterious woman? Why was she collecting plants in Canada’s north so long ago? How on earth did her specimens end up at the Manitoba Museum? Clearly figuring all this out was going to require some serious detective work.

By examining the collection I was able to come to some conclusions about who Mrs. Crawford was and what she was like. First, she was clearly an educated woman as she was both literate (her penmanship is lovely) and able to correctly identify the scientific (Latin) names of the plants she collected. Second, she had access to natural history books and enough leisure time to engage in a hobby, suggesting that her family was somewhat well-off. Third, she was a nature lover and probably a bit of an adventurer. She described the habitat of one plant as being “amongst moss in swamps” so she was probably willing to hike in inhospitable places in search of interesting plants. I surmised that she was probably from an upper-middle class family and that her presence in Labrador was most likely as a visitor or temporary resident. Although her husband was of Scottish ancestry, she is not necessarily Scottish as her maiden name was not indicated.

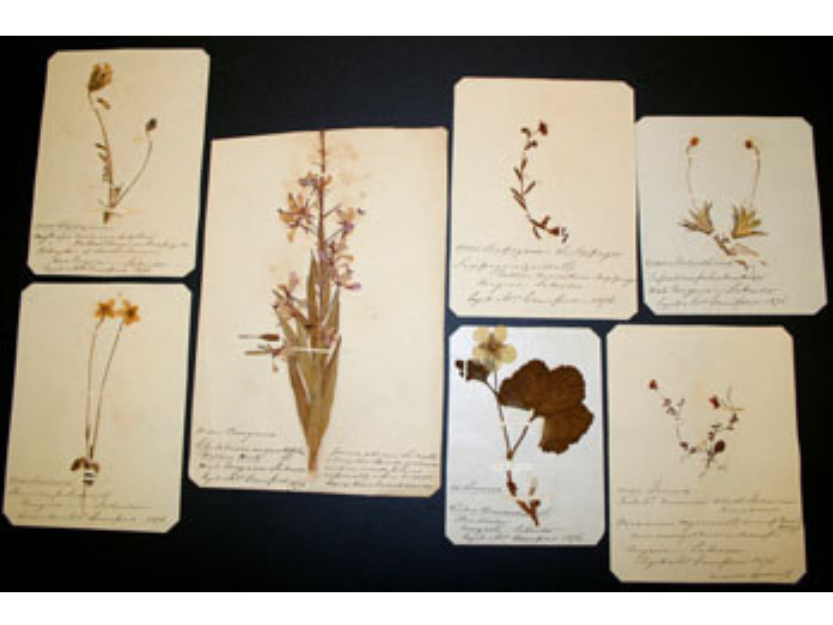

Some of Lizzie Crawford’s pressed plants from Labrador.

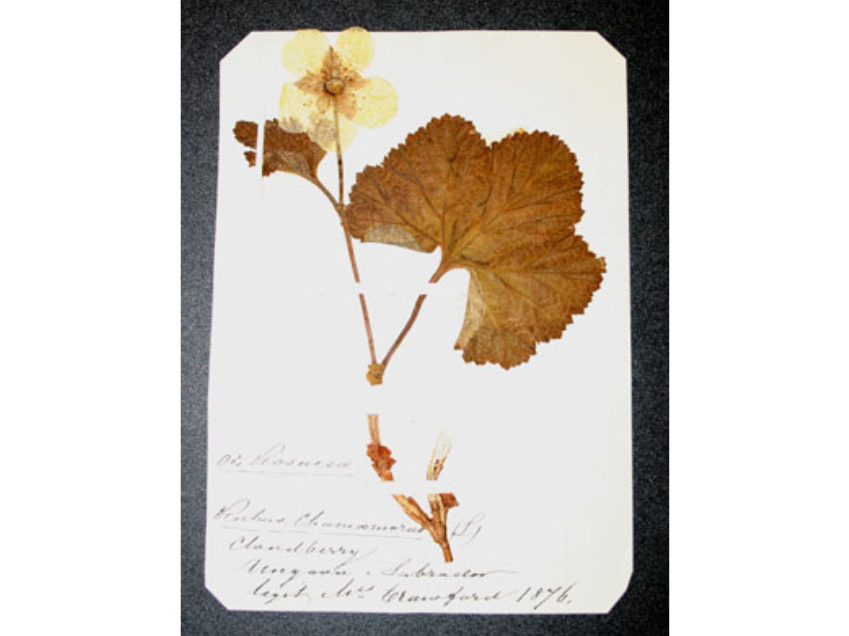

A specimen of swamp cranberry collected “amongst moss in swamps”.

Next I needed to know a little bit more about the history of Labrador. What kinds of people were living in northern Labrador in 1876? I began searching history publications for information about Scottish immigrants. I determined that there were three likely professions for Mrs. Crawford’s husband: missionary, merchant, or employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). I decided to explore the HBC archives since a link to this company might explain how the specimens ended up in Manitoba.

I quickly hit the jackpot: a Robert Crawford had worked for the HBC from 1854-1877, mainly at various forts in Ontario. However, from 1875-1877 he worked at Fort Chimo in the Ungava district of what is now Labrador! This couldn’t be a coincidence; I was sure I had found Lizzie’s husband. I hit a snag however as the Record of Employment (ROE) indicated that his wife was named Mary. Fortunately, there was a question mark after the “Mary(?)” indicating some uncertainty. Maybe the record of employment was wrong. I decided to search Ontario’s marriage records as the ROE indicated that Mr. Crawford’s wife’s family was from Brockville, Ontario. I was able to determine that Robert Crawford married an Elizabeth Miles in 1863. Victory! I was right! I felt like dancing. In fact, I think I did.

Image: A faded but beautiful cloudberry specimen.

Armed with her maiden name I was able to determine that her father also worked for the HBC and was no other than Robert Seaborn Miles, an Englishman who rose to the position of Chief Factor. Her mother was Elizabeth “Betsey” Sinclair who had at one time been the “country wife” of Sir George Simpson, Governor-in-Chief of Rupert’s Land from 1821 to 1860. Country wives were the First Nations or Metis common-law wives of fur traders. In fact, Lizzie had a half sister, named Maria, who had been fathered by Sir George. In another interesting twist, one of Lizzie Crawford’s aunts was Mary (Sinclair) Inkster, wife of John Inkster. The Inkster’s home and general store was one of the first residences in Winnipeg and has been preserved as the Seven Oaks House Museum on Rupertsland Blvd. Therefore, anyone who is related to John and Mary are distant cousins of Lizzie Crawford.

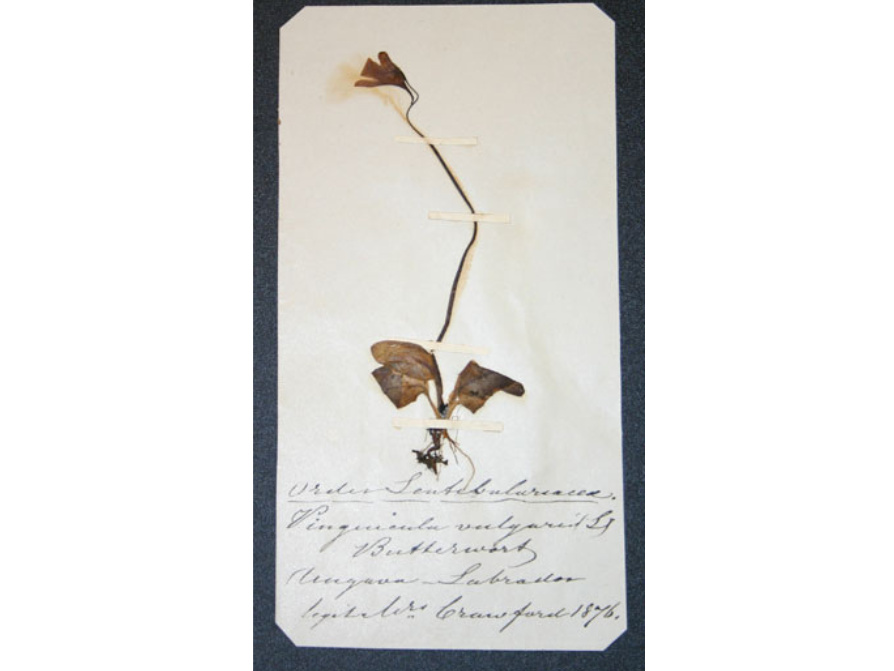

Image: The butterwort (Pinguicula vulgaris) specimen collected by Lizzie Crawford.

So how did the specimens end up at the Manitoba Museum? I needed to track the Crawfords movements after Mr. Crawford retired from the HBC in 1878. Using the internet I was able to find enough documents to piece some of the puzzle together. The Crawfords moved to Indian Head (now part of Saskatchewan) in 1882 to open a general store and Mr. Crawford entered politics, becoming a member of the first council of the Northwest Territories from 1886-1888. During this time the Crawfords may have been involved in the Manitoba Historical and Scientific Society (MHSS), which established in 1879. I suspect that the 28 specimens that I have were given to the MHSS directly by the Crawfords or by their daughter Maggie, eventually ending up here at the Museum. Additional specimens of Mrs. Crawford ended up in herbaria at the University of Montreal and the Canadian Museum of Nature. In fact, Dr. John Macoun (the naturalist with the Geological Survey of Canada), mentioned one of her specimens (Pinguicula vulgaris) in his list of the flora of Labrador in the book “Labrador Coast: A journal of two summer cruises to that region” by A. S. Packard in 1891.

It would be wonderful to find some of Lizzie’s descendants to show them her specimens and also see if they have any old journals, books, letters, or diaries that would tell me more about Lizzie’s collecting activities and why she was interested in natural history. If you are somehow related to Lizzie or Robert Crawford please feel free to get in touch with me as this Museum mystery is still not fully solved.