Posted on: Friday November 13, 2020

By Dr. Leah Morton, past Curatorial Assistant in History

The Winnipeg General Strike is central to Winnipeg’s collective consciousness; however, Black workers and union members are often overlooked in narratives of the strike. This blog post looks at John Arthur Robinson, a Black railwayman who is featured on the Winnipeg Personalities wall in the new Winnipeg Gallery.

Like many other Black men, Robinson worked as a porter on sleeping cars. Robinson worked for the Canadian Pacific Railway, but all the big Canadian railway companies had luxurious sleeping cars so well-to-do passengers could travel in comfort and style. Porters had to take care of all of the passengers needs. Duties included, but were not limited to:

- Keeping the sleeping car warm (with coal stoves) in the winter and cool (with giant ice blocks) in the summer

- Serve food and drinks

- Babysit children and drunken passengers

- Set up beds and turn them into seats during the day

- Remember every passenger’s schedule

- Shine passengers’ shoes

- Keep passengers entertained

- Keep washrooms clean

Porters were treated in condescending, racialized ways. Regardless of their actual names, porters were usually called “George” or “boy” and were expected to play the role of the smiling black servant, despite the fact that they were usually given 72-hour shifts without sleeping accommodations.

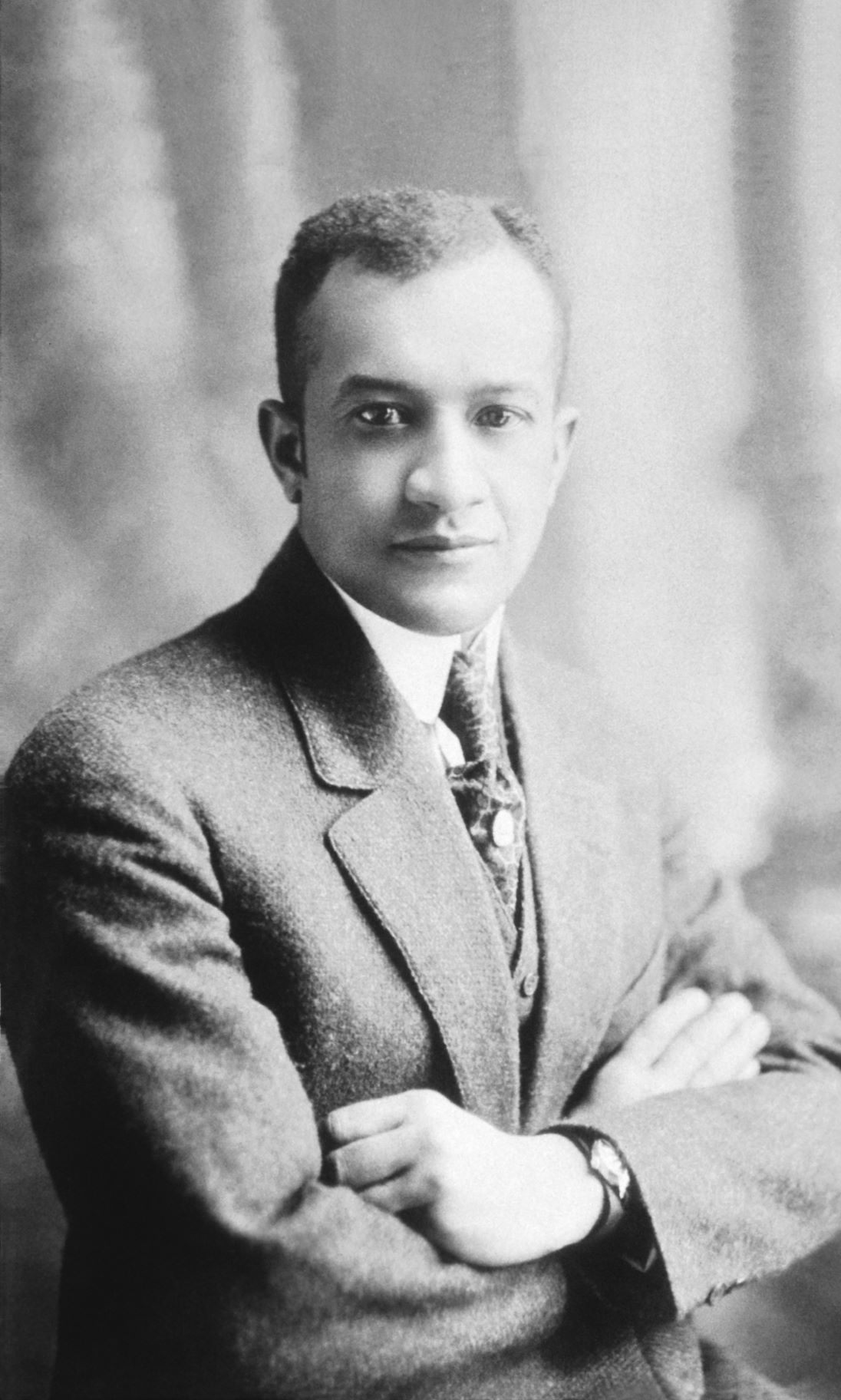

Image: John Arthur Robinson was born in the West Indies and moved to Winnipeg around 1909. Railway companies actively recruited men from the American South and the West Indies, so it is possible that he came to Canada in this way. “Back Tracks to Railroad Ties” exhibit and black history research collection, P6899/2, Archives of Manitoba

Canadian Rail Unions

Railwaymen worked in a dangerous, tough industry, and they were often militant unionists; however, they worked to keep their unions for whites only. From its inception in 1908, the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE) excluded black workers and pushed for separate negotiating schedules and wages for Black and white workers.

Undaunted, John Arthur Robinson started a different union – the Order of Sleeping Car Porters (OSCP] – in 1917, a time when Winnipeg’s working-class consciousness was blossoming. The Winnipeg General Strike in May and June 1919 was a pivotal time for many, the members of the OSCP included. The OSCP, despite being marginalized and racialized within their workplace, voted on May 20th in favour of a sympathy strike. The OSCP also donated $50 – not a small sum in 1919 – to the strikers’ fund, a gesture for which the Strike leaders thanked them in their newspaper, the Western Labor News. In a show of solidarity, after learning from Robinson that the railways were bringing in scabs, the Strike Committee publicly “defended black Canadian railroaders; right to employment in the press, denouncing the company’s tactics.”

Robinson and other OSCP members paid for their actions during the General Strike. Many were laid off or fired from their jobs. Despite this, Robinson continued to press for better wages and working environments for Black railwaymen. He was successful, for example, in getting the CPR to pay its porters the same wages as porters working for other railway companies.

Another goal Robinson had was to get the larger, national, and all-white CBRE to allow the Black members of the OSCP to join. Some CBRE members agreed with Robinson, but the most the CBRE would allow was for the OSCP to join as “auxiliary” members. They stayed in that position – as a racialized lower tier – until 1965. Robinson, for his part, continued to critique the union and the CPR for treating “black railwaymen as a disposable class of workers.”

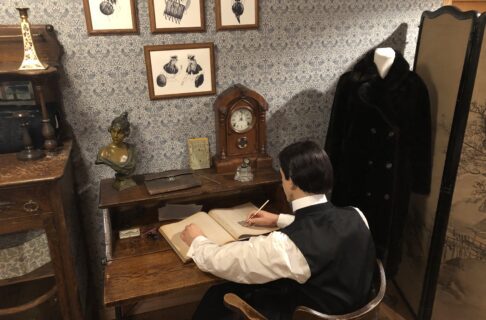

Image: The Railway Porters Union Band of Winnipeg poses here in front of the Bank of Montreal at the corner of Portage Ave. and Main St., May 1, 1922. Foote 291, L.B. Foote Fonds, P7393/4, Archives of Manitoba.

The Black Community in Winnipeg, 1920

Railway workers generally lived in a railway hub and Winnipeg was certainly that. They were at the centre of a vibrant black community in the city. Geographically, the black community in the early 1900s lived around the CPR station near Main and Higgins. While most members of the OSCP spent a lot of time at the union office on Main Street, the broader black community was comprised of families, workers, churches, restaurants, and more. Their stories, like that of Robinson and the OSCP, should be told – and listened to – as part of Winnipeg’s history because they are a part of this city’s fabric.

For more information, check out: Mathieu, Sarah-Jane. North of the Color Line: Migration and Black Resistance in Canada, 1870-1955. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010)