Posted on: Friday July 3, 2020

Eighty years ago, Manitoba botanist Charles W. Lowe collected a plant from the West Hawk Lake area, not realizing that it would be the last time anyone would collect it in this province again. This June, I embarked upon a journey to see if that elusive plant was still hiding somewhere in Whiteshell Provincial Park.

West Hawk Lake was where the rare climbing fumitory (Adlumia fungosa) plant was found in 1940.

My scholarly journey commenced when I began working on a revised Flora of Manitoba; a book that will describe all the plants in the province. I searched through old papers, herbarium specimens and websites to compile a preliminary list of species for the province. Many new species had been confirmed or found since the publication of the last Flora of Manitoba in 1957, but there were also a few species that seemed to have disappeared. These plants are considered “historic” species: plants that had definitely been collected here in the past but not again for many decades. Are these species now locally extinct (i.e. extirpated) or are they still hiding in some remote area of the province? I’ve spent the last few years looking for some of them.

In some cases, mainly in Manitoba’s prairies, the habitats of the historic plants appear to have been destroyed by cultivation or construction activities. In other cases, the historic species’ seem to have been displaced by exotic plant species like smooth brome (Bromus inermis), which were introduced as a forage crop. However, the disappearance of climbing fumitory (Adlumia fungosa) was a bit of a mystery. My research indicated that it had been collected in the West Hawk Lake area, which is still largely intact. Why then was it seemingly gone?

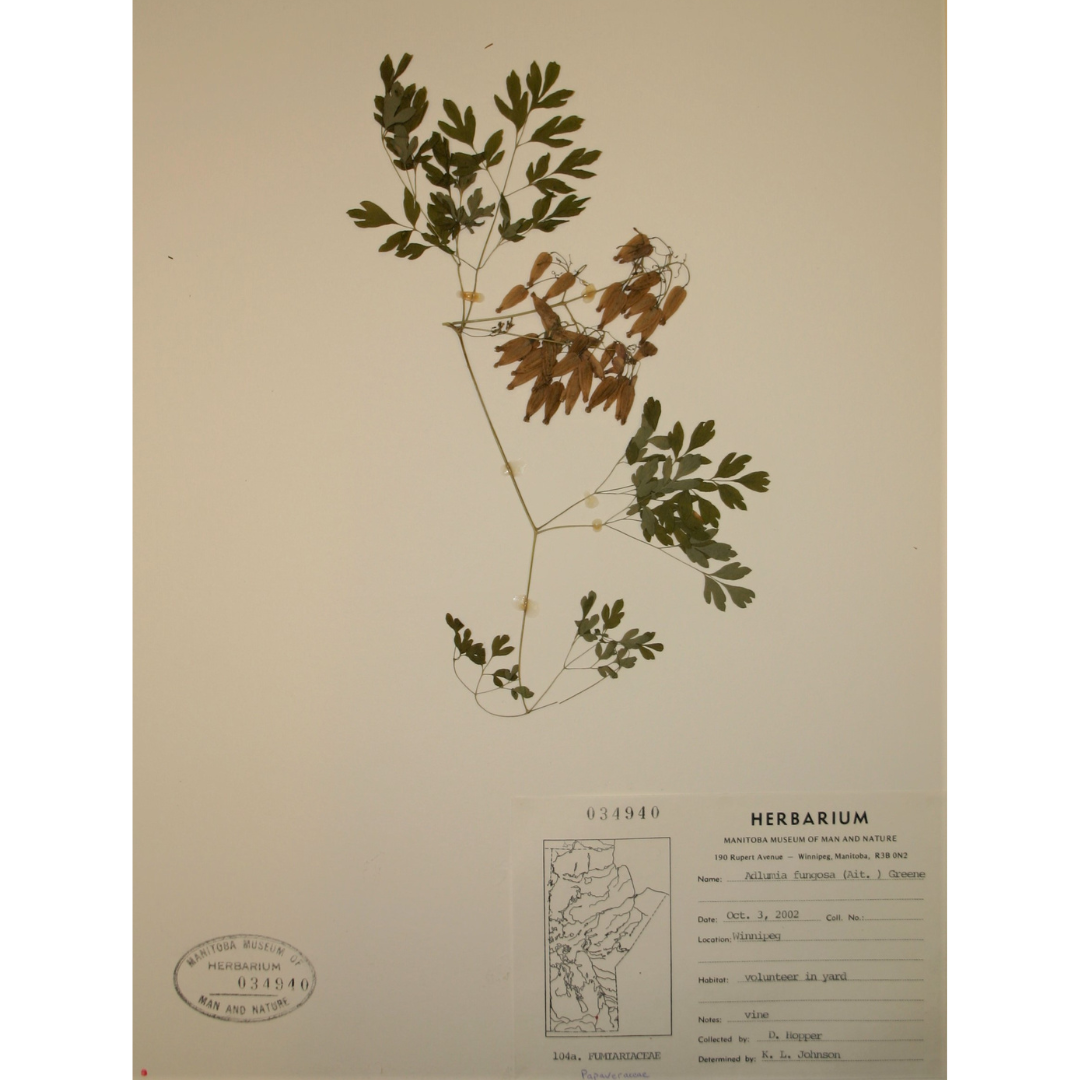

This is the only specimen of climbing fumitory (Adlumia fungosa) in the Museum’s collection; it was grown from seed in a Winnipeg garden. MM 34940

While searching for more information, I discovered that this species is not common anywhere it occurs in the wild, in part because it is a biennial. That means its seeds germinate and grow a few leaves the first year, producing flowers and fruits only in the second year. Then it dies, remaining in the soil as a seed until its germination is triggered. But what triggers the germination? The references I found note that fires, windstorms and insect outbreaks that open up the forest canopy are likely triggers. But the soil cannot be severely damaged the way it often is with logging so apparently you don’t tend to see it in clearcuts. Plus, it likes rocky, acidic soils that stay consistently moist in places that are not too windy, and that have some trees or cliffs that it can climb up since it is a vine. In short, it appears to be adapted to thrive in very particular types of environments that don’t occur all that often anymore.

I searched for hours along the rocky, rooty Hunt Lake trail where this species may have been collected 80 years ago.

A rocky, recently burned area in the park where I searched in vain for climbing fumitory (Adlumia fungosa).

A close relative of climbing fumitory (Adlumia fungosa), pink corydalis (Corydalis sempervirens) grew in the recently burned area.

I began to wonder why Lowe found this species in the 1940’s. Since I couldn’t find any records of a large forest fire in the late 1930’s near West Hawk Lake, I thought that perhaps it was construction of the campgrounds and roads during that time that created a suitable opening in the canopy for this species. Decades of fire suppression, which improved greatly after World War II due to the use of aerial water bombers, have likely prevented the creation of the post-fire habitats in this area that the species needs. So even though humans have not changed this habitat by directly destroying it, we have changed it by altering the natural fire cycles that occurred before Europeans arrived. The presence of so many cottagers in the West Hawk and Falcon Lake areas means that any natural fires that do ignite will likely not be allowed to get anywhere near the recreational areas to protect human lives.

After so many years without disturbance, any seeds of climbing fumitory that were in the soil seed bank have likely died, and if that has happened, then this species may indeed be extinct in Manitoba. However, if an insect outbreak or windstorm damage occurs in the right spot, all may not be lost. One thing I was reminded of during my trip is that the boreal forest is vast and, in many places, completely inaccessible to humans. Climbing fumitory may still be hiding somewhere in this vast forest, waiting for some intrepid individual to stumble across it again.