You may have heard the old saying that “nature abhors a vacuum”. To understand this expression, you probably won’t need to look any farther than your own lawn. Although lawns may start out as monocultures of Kentucky Bluegrass (Poa pratensis), they never stay that way. Inevitably, species like Common Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) show up, prompting a flurry of weeding and spraying of herbicides. We are told by lawn care companies that “healthy lawns won’t allow weeds to grow” but that statement is simply not true. Just look at any wild ecosystem in the world. Is it a monoculture with just one species? No, there are always many species. Weeds eventually invade lawns because monocultures are NOT natural. Ecosystems want to return to a natural state.

Native prairie ecosystems are natural polycultures: systems with many plant species. © Manitoba Museum

What’s really under the ground?

To help people understand the natural state of a prairie grassland, the Manitoba Museum created an exhibit called “Anchoring the Earth” in the new Prairies Gallery. This exhibit shows the root systems of native plants. Some roots are shallow, like lawn grasses, but others are deep (over 4-m!). June Grass (Koeleria macrantha) grows early in the spring, then goes dormant. Other species grow mostly at the height of summer, like Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardi). In addition to the grasses, there are also taprooted plants like White Prairie-clover (Dalea candida). Every possible habitat or “niche” in the ecosystem is exploited by one species or another, the complete opposite of a lawn.

One of the new exhibits at the Manitoba Museum shows what native prairie ecosystems look like under the ground. © Ian McCausland

The weed you can eat

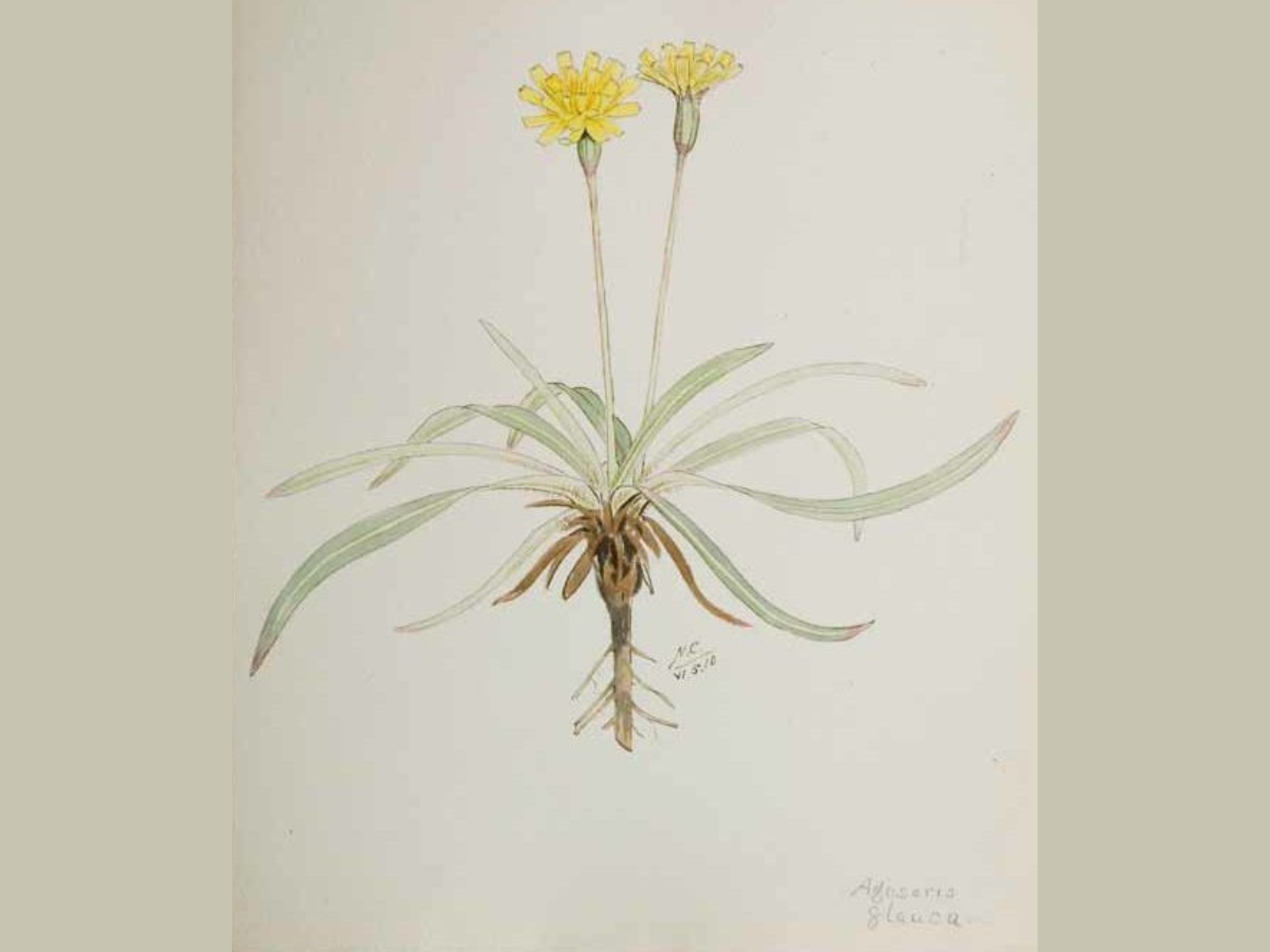

Dandelions are native to Eurasia but were introduced to the Americas. They have taproots, which grow deeper than the shallow roots of turf grasses. Dandelions exploit the nutrients and water deeper in the soil, just like the native False Dandelion (Agoseris glauca). Far from being a useless weed though, you can eat all parts of a dandelion. I’ve eaten dandelion greens in spring, made fritters with the flowers, and roasted the roots to make tea and bake a cake (when the roots are ground up, the powder is similar to cocoa). Just 100 g of raw dandelion leaves have 64% of your daily required vitamin A, 42% of your vitamin C and a whopping 741% of your vitamin K. Sometimes when life gives you lemons, you just need to make lemonade!

False Dandelion (Agoseris glauca) is a native plant with deep taproots similar to the non-native dandelion. © Manitoba Museum, H9-23-260

Lawn Origins

But why did lawns even become popular in the first place? In Europe, in the 16th century, wealthy landowners began growing lawns to flaunt their status. They didn’t need the land to grow food, they were rich enough to grow completely useless grass on their property instead! As the European middle class began to grow, they also aspired to demonstrate their wealth by growing at least small patches of lawn, if they could. This Western appreciation of the lawn aesthetic still remains with us today, but there are signs that its time is up. Concern about the impact of lawn care pesticides on human health and vulnerable pollinators has prompted many municipalities to enact bans on these chemicals.

Further, the popularity of polyculture lawns is experiencing a resurgence. Polyculture lawns more closely mimic a natural ecosystem by including both grasses (ideally, low growing native species like Blue Grama a.k.a. Bouteloua gracilis) and low growing, broad-leaved plants, such as clover (e.g. Trifolium), native violets (e.g. Early Blue Violet a.k.a. Viola adunca), pussytoes (Antennaria spp.) and yes, maybe even some dandelions. Broad-leaved plants provide pollinators with food, and some species, like legumes, naturally add nitrogen to the soil, reducing the need for fertilizers. In shady areas where grass won’t grow well anyway, ground covers of taller, native plants like Ostrich Fern (Matteucia struthiopteris), Western Canada Violet (Viola canadensis) and Canada Anemone (Anemone canadensis) are great alternatives.

Early blue violet (Viola adunca) is a short, native violet that can add biodiversity to your lawn. © Manitoba Museum

White clover (Trifolium repens) may be considered a weed by many lawn purists, but it was once a staple in lawn seed mixes, as clover raises the nitrogen level. © Wikimedia Commons

Trying to keep your lawn “weed” free is like running on a treadmill: you spend lots of energy but you never get anywhere. Why not embrace the diversity of plant life, and save your money and back-breaking labour for something else?