It’s almost Valentines Day and the flower that most people associate with that holiday is bright red. Long-stemmed red roses have long been the flower of choice for people wooing their sweethearts. But if you’ve ever gone hiking in a wild Manitoba grassland or forest, you might have noticed that the roses we have here are pink, rarely white, but not red. In fact, there are no bright red wildflowers in our province. Why not?

Why Flowers Have Colour

To understand the lack of red flowers in Manitoba, we need to think about why flowers exist at all. Flowers are the reproductive organs of plants; they produce eggs and/or pollen. Since plants can’t move around to find a mate, they often use animals to move the pollen from one flower to another. Successfully transferred pollen fertilizes the eggs of the receiving flower. To attract animals, plants grow structures that animals will find attractive, like beautiful or unique scents, and petals with eye-catching colours. They also usually reward the pollinator with nectar.

Scarlet Paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea) is one of the reddest wildflowers we have in Manitoba, but it tends to be orangey-red rather than bright red. © Manitoba Museum

Wild Columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) attracts hummingbirds, but butterflies, moths and bees are also important pollinators of this plant. © Manitoba Museum

The Nature of Colour

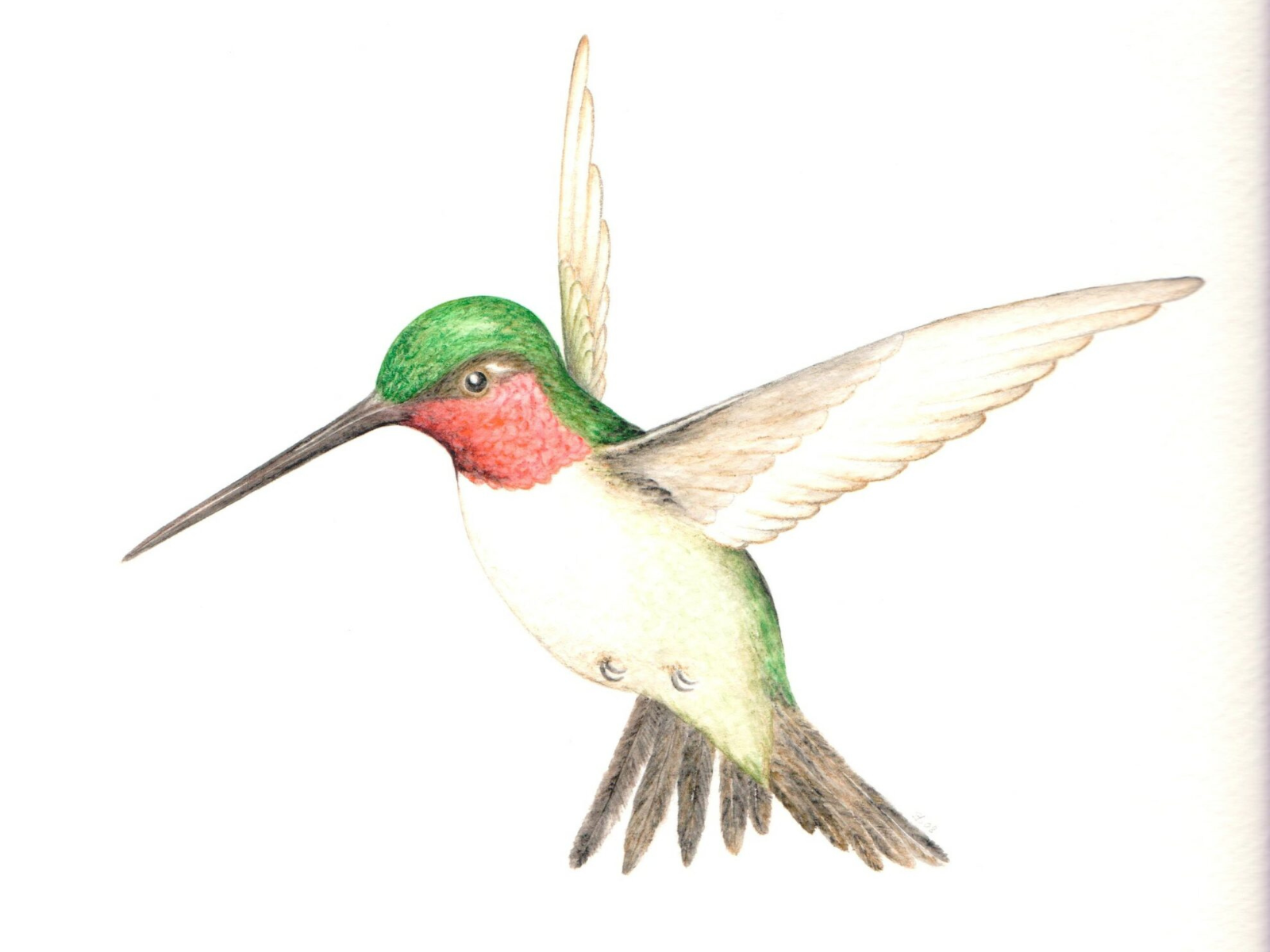

Colour exists because different surfaces reflect different wavelengths of light. Light is made up of a whole spectrum of colours, evident in a rainbow or when light shines through a prism. Just like some animals have a better sense of smell than others, they also see things differently. Birds and humans can see red flowers quite well, but most insects cannot. To an insect, red is difficult (though not impossible) to tell apart from green leaves. For this reason, areas where birds are common pollinators (such as tropical rainforests) tend to have lots of red flowers. Areas with mostly insect pollinators typically have lots of yellow and violet flowers. In Manitoba, our only bird pollinators are hummingbirds, the most common being the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris).

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris) move pollen from flower to flower in exchange for a nectar reward. Illustrated by Silvia Bataligni © Manitoba Museum

Abundant Insect Pollinators

Insects are the most abundant pollinators in Manitoba, so most of our flowers are highly attractive to bees, butterflies, moths, flies, wasps and/or beetles. Flowers that are orange, yellow, blue and violet are most attractive to insects, as these colours are readily visible to them. However, unlike humans, insects can also see into the ultraviolet (UV) range. This ability explains the presence of so many, seemingly white flowers in the province. Flowers that we see as pure white or plain yellow, actually usually reflect UV rays, and look much different to insects than to us. White flowers are also often pollinated by moths, because white is more visible in moonlight than any other colour.

Small bees and flies, not birds, pollinate our wild roses, including Prairie Rose (Rosa arkansana). © Manitoba Museum

Many insect-pollinated plants, like Dandelions (Taraxacum sp.) have patterns that are visible only under UV light (left) © Wikimedia Commons CCA-SA 4.0

Why do cultivated roses look different from wild roses?

Humans have been cultivating roses for thousands of years. In the process, we selected features that we find attractive but that make them largely unattractive to pollinators. Colour is one factor. Insect pollinators do not usually visit red roses because they can’t see them very well. Further, cultivated roses have many, densely packed petals (not just five like the wild ones), that cover up the pollen-containing anthers, making them difficult for pollinators to access. So, the end result is that these beautiful flowers now function only as aids to human, not wild, romance.

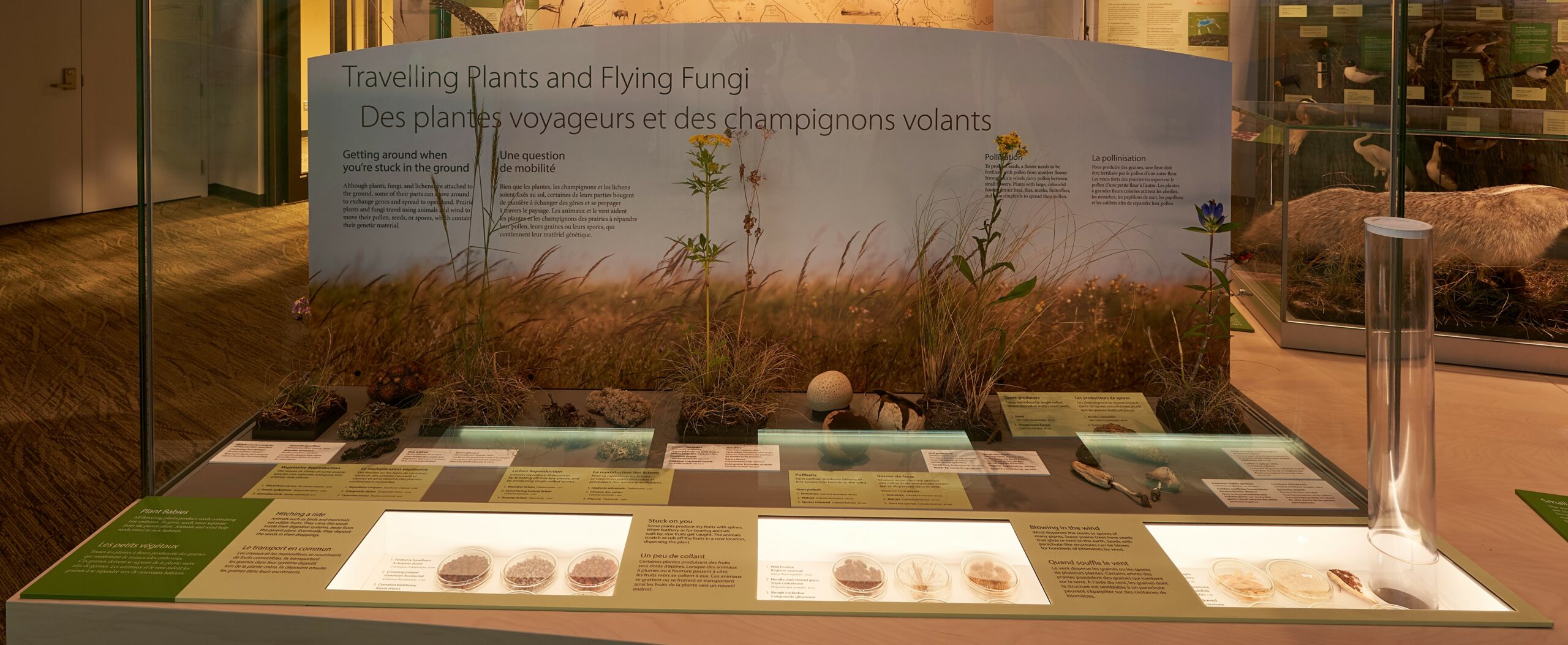

The Manitoba Museum’s new Prairies Gallery has a whole exhibit on pollination where you can see what native pollinators look like. © Ian McCausland/Manitoba Museum