September 1st of 2014 marked the grim anniversary of the death of the last passenger pigeon on Earth. It’s extinction is probably the only one for which an exact hour of demise is recorded; the last individual was a captive bird, named Martha, that expired at 2pm local time at the Cincinatti Zoo. The disappearance of this species is almost impossible to comprehend, as it was once the commonest bird in North America, perhaps even the world, with population estimates of between 3 and 5 billion – yes, that’s billion – in the mid-1800s.

But the capacity of humans to destroy knows no bounds. The awe-inspiring flocks that were described as darkening the sky from horizon to horizon, and the massive breeding colonies that numbered in the tens of millions were slaughtered by market hunters and shamefully wasted by hungry locals alike. Unfettered exploitation along with changes in environment due to deforestation resulted in the shocking disappearance of passenger pigeons from the wild by about 1900.

Local reports of passenger pigeons from Winnipeg newspapers, the upper from the Manitoba News-Letter of May 31, 1871 and the lower from the Manitoba Free Press of September 19, 1874.

Although Manitoba never hosted massive colonies, large flocks provided food for First Nations peoples and hungry homesteaders, and were important enough to frontier life to merit frequent mention in local newspapers as “wild pigeon” or merely “pigeons.” Passenger pigeons bred in small groups in the south of the province and were seen as far north as Hudson Bay.

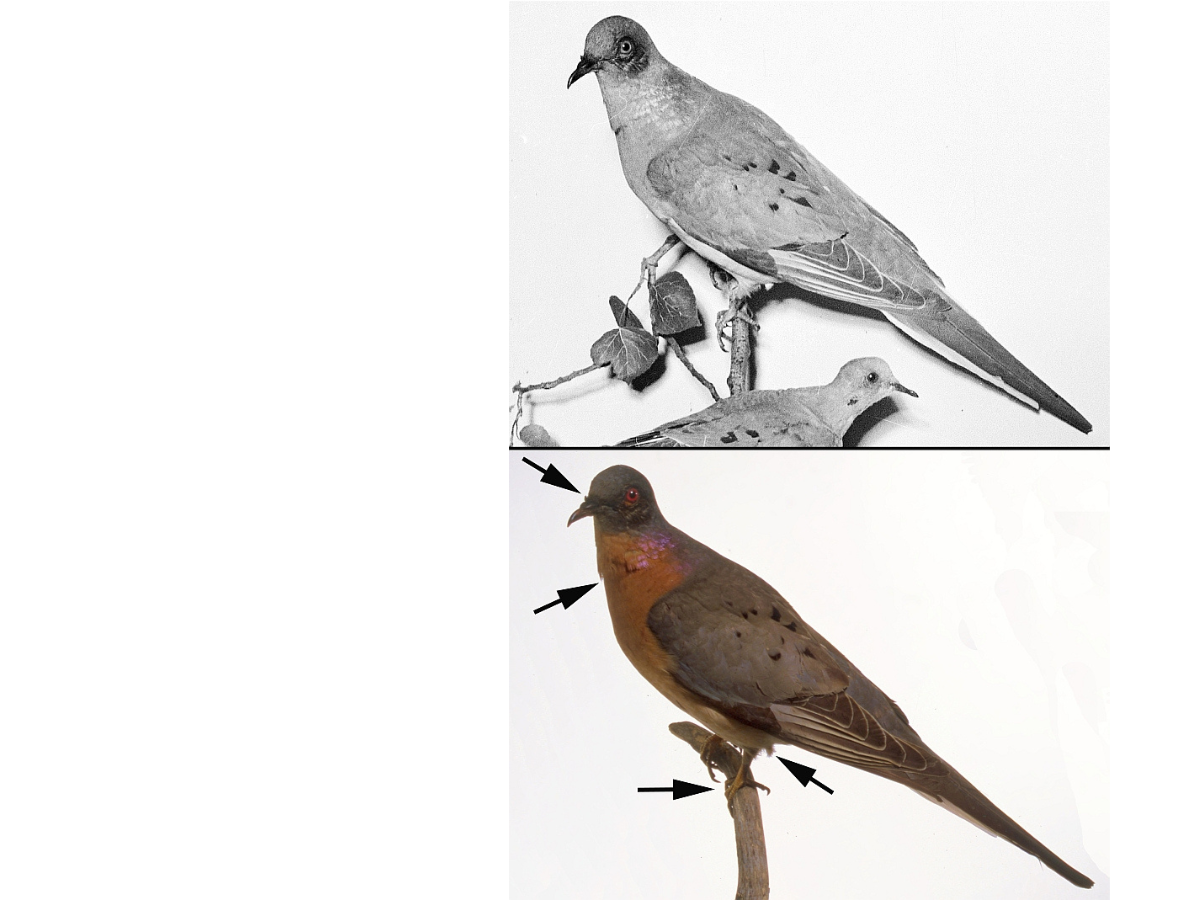

A relatively recent addition to the Museum’s passenger pigeon collection, a beautiful mount of a female generously donated by the Delta Waterfowl Foundation in 2013. Note the female lacks the orange breast and bluish back of the male, and is slightly smaller, about 37 cm. MM 1.2-5437

In contrast to their abundance in the 19th century, there are relatively few specimens of passenger pigeons in natural history museums and even fewer of those that have information on when and where they were collected. This is in part because systematic museum and research collecting in North America was still relatively new, and because passenger pigeons were so common; who carefully collects crows or starlings today? The Manitoba Museum has five taxidermied specimens of passenger pigeon.

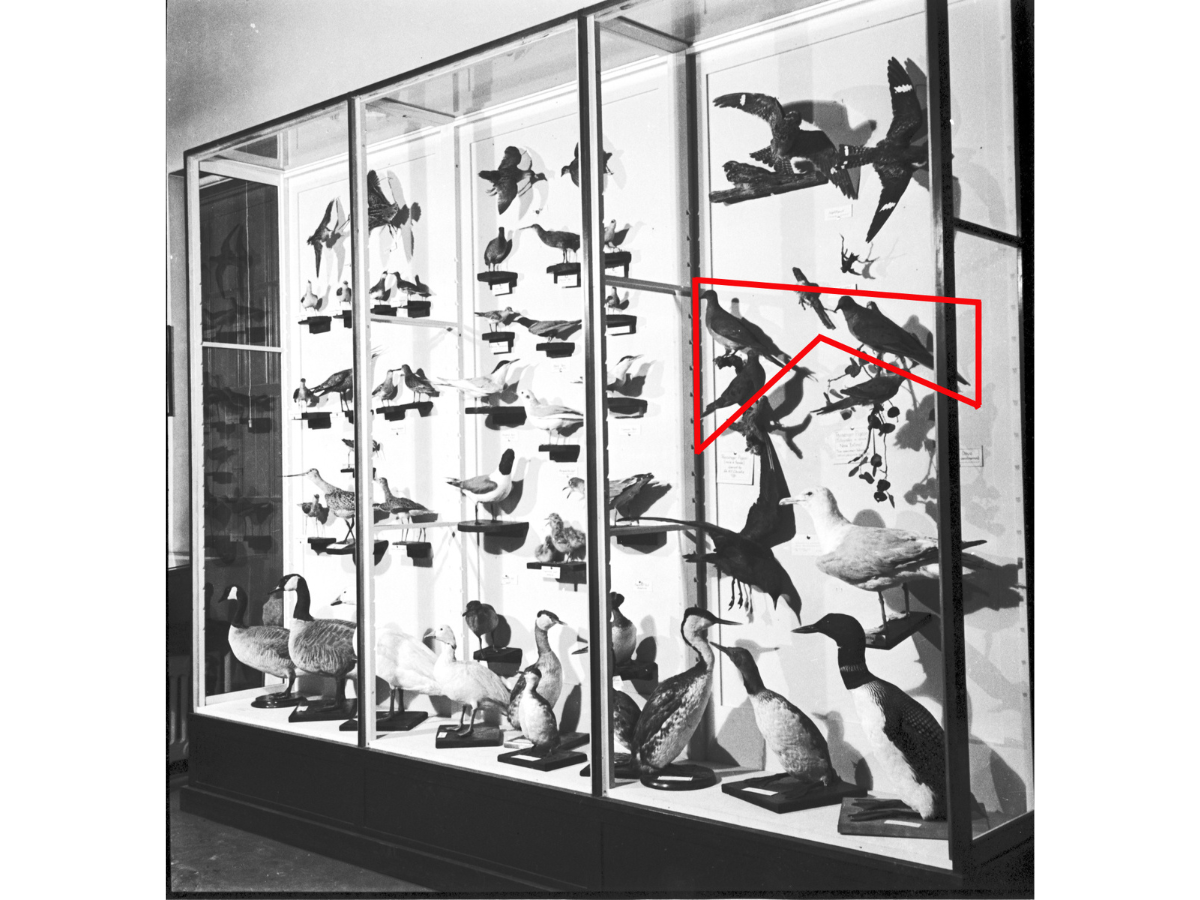

Some of the old bird cases as they were in the Civic Auditorium in the mid-1930s. The passenger pigeons are marked within the red lines. These three mounts are still in the Museum collection today.

Until recently, all of the Museum’s passenger pigeons were of unknown locality – we weren’t even certain that our birds were actually from Manitoba! Record-keeping was not always thorough in the 1930s when some of them came into the possession of the original Manitoba Museum, and the others were in private collections where their exact histories have been lost. However, while examining some photographs of the exhibits in the old Civic Auditorium from the 1930s, I noticed that some were of the bird cases. One of these had three of our pigeon specimens on display! And another photo showed that one mount had very specific data on its label just below it tacked to the back of the case:

Did the Museum still have this particular specimen? Comparing our present collection with the photographs, I was able to determine that one of the five birds we have is an exact match for the Winnipegosis specimen that had been on display in the 1930s. This is especially important because detailed information on this bird was published by G.E. Atkinson in 1904, a taxidermist and naturalist from Portage la Prairie. He prepared this specimen and noted its date of collection as April 10th of 1898 – the last specimen ever collected in Canada!

Comparison of the 1898 Winnipegosis specimen as it appeared in the Civic Auditorium in the mid-1930s (top) with a photo of one of our specimens (MM 1.2-2391) today (bottom). Arrows show the unmistakable features (tuft of feathers at base of bill, ‘ruff-like’ neck feathers, foot shape, leg feathering) that indicate that these are the same specimens. The pattern of black spots on the back are also distinctive.

So the specimen has come full circle in its history with the Manitoba Museum. It was first on display in the mid-1930s in the Civic Auditorium, was in our collections storage for decades, and is now on exhibit again 90 years later at Rupert and Main. It remains, after all that time, still able to perform the unfortunate, but important function as a flag-bearer representing all extinct species and as a warning of where careless attitudes to our environment can lead us.

Aldo Leopold, the famous Wisconsin environmentalist, said in memory of the passenger pigeon in 1947:

“There will always be pigeons in books and in museums, but these are effigies and images, dead to all hardships and to all delights. Book-pigeons cannot dive out of a cloud to make the deer run for cover, nor clap their wings in thunderous applause of mast-laden woods. They know no urge of seasons; they feel no kiss of sun, no lash of wind and weather; they live forever by not living at all.”

And indeed, the Museum’s passenger pigeons will not, unfortunately, repopulate our skies. But they will always be here, for that is the value of museum collections – archives of natural history and silent witness to changes in our world. Our collections provide opportunity to study, marvel, contemplate, and learn. And although there are no more passenger pigeons in the wild, they can still be found in museums. I invite you to the Manitoba Museum and the new Prairies Gallery (2021) to see the last passenger pigeon ever collected in Canada, along with one other, and to reflect on their fate as well as our own place in the world.

If you have any further information on these specimens or others, please contact the Museum.