Posted on: Tuesday January 31, 2017

After Manitoba entered Confederation in 1870 and the Canadian government negotiated Treaty No. 1 with First Nations leaders, Canada began to actively engage potential immigrants to settle and farm the prairies. The first two groups that arrived in large numbers were English speaking Ontarians and German speaking Mennonites from eastern Ukraine. This first large wave of immigration to Manitoba would begin the irrevocable transformation of the environment and the economy of the province forever. The success of the Mennonites in particular may have helped open the door to other immigrants who did not speak English and had different religious backgrounds compared to the English Protestants and French Catholics who dominated political life in Canada. Icelandic, Jewish, Ukrainian, and many immigrant groups from Eastern Europe began entering the province by the 1880s.

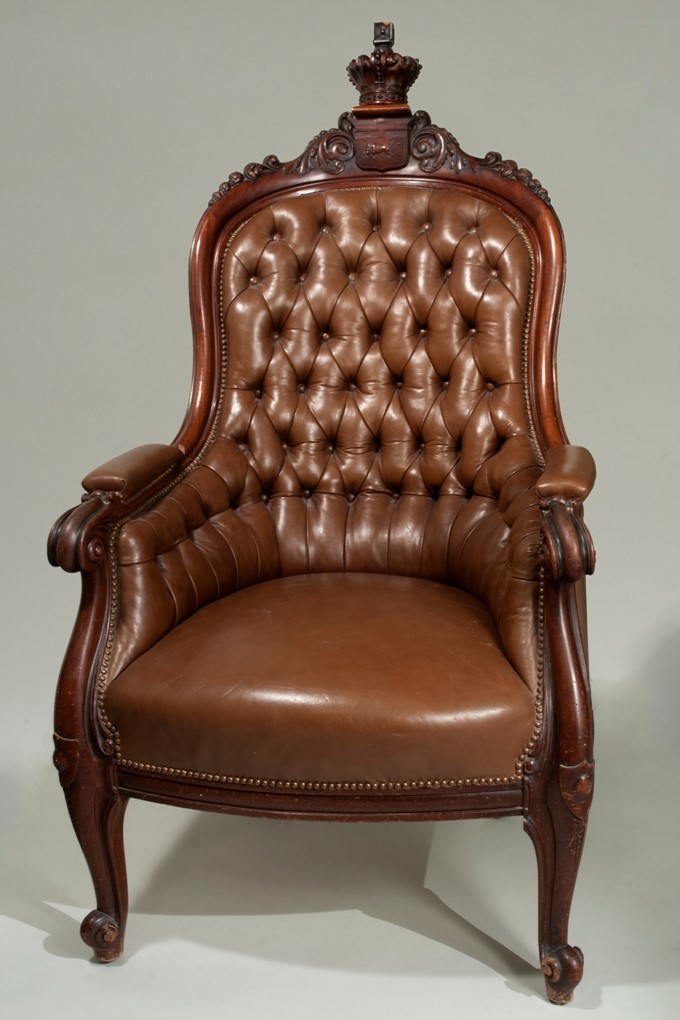

Our new exhibit “Legacies of Confederation” features a number of personalities, including William Hespeler (1830-1921) who played an incredibly important role in immigration from the 1870s to the 1890s. The exhibit features his Speaker’s Chair, used in the Manitoba Legislative Building between 1900 and 1903. In 1899 Hespeler entered provincial politics, winning the rural seat of Rosenfeld. In 1900 he was chosen as the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, which he held for three years before retiring. The carved wooden armchair was built for his position as Speaker and he retained it after he left politics. It has been handed down to generations of his descendants since he died in 1921. The chair was donated to the Manitoba Museum in 2016 by his great-great-grandson Michael Boultbee of Victoria, BC.

William Hespeler Speaker’s Chair, 1900, wood and leather. H9-38-512, copyright Manitoba Museum, photograph by Rob Barrow.

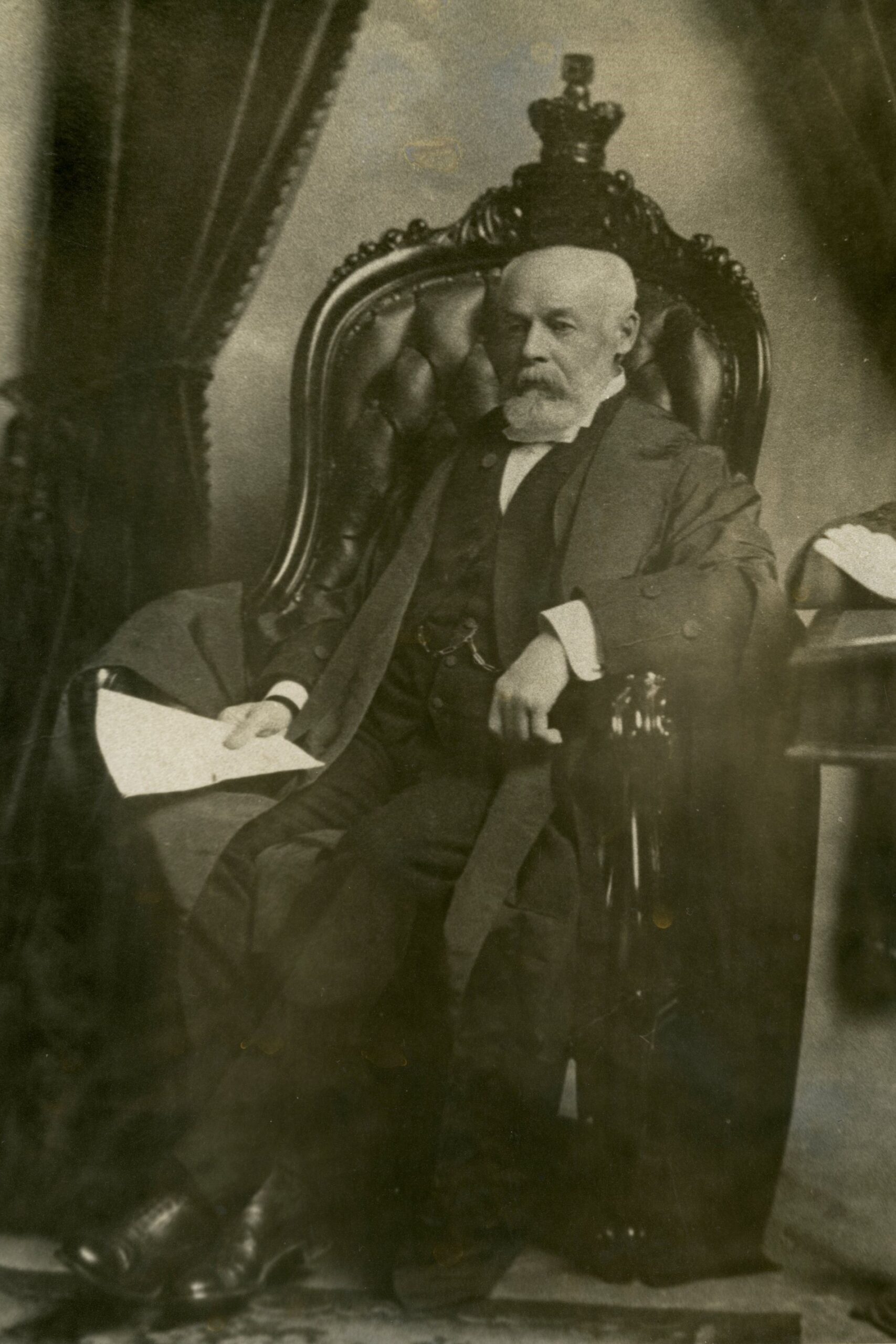

William Hespeler seated in the Speaker’s Chair, ca. 1903. Courtesy Jeremy Hespeler-Boultbee.

Detail of crest rail, including the seal of Manitoba (Bison and English Cross of St. George) surmounted by a large crown. This symbolizes the power of the Speaker as an authority in the Legislative Assembly and the role of Manitobans as subjects under the British crown. H9-38-512, copyright Manitoba Museum, photography by Rob Barrow.

Hespeler was born to a wealthy family in Baden, Germany and moved to Berlin, Canada West (that is, Kitchener, Ontario) in 1850. After business success in establishing mills and distilleries in Canada, he moved back to Baden with his sick wife Mary Keatchie in 1872.

In Baden, Hespeler was informed by the Canadian government that a large population of Mennonites had grown dissatisfied in their colonies in Ukraine. Many felt their religious freedoms were being threatened as a new schooling system and military service were enforced. Mennonites were looking to emigrate, and the Canadian government hoped they might migrate to farm the lands of southern Manitoba. Hespeler went to Ukraine and convinced Mennonite delegates to visit southeastern Manitoba in 1873, which led to the migration of 7000 Mennonites to Manitoba. Along with Anglo-Ontario settlers, this comprised the first wave of mass migration into the province. It would also set the stage for more waves of Mennonite migration to Canada in the 20th Century. Not only did Mennonite settlement in Manitoba help prove the viability of farming on the open prairie, it also had long term effects for Mennonite populations around the world, as they realized Canada could be a safe homeland.

After this success William Hespeler was appointed as dominion immigration agent for Manitoba and the North-West Territories. As such he assisted with the immigration of Icelanders, Germans, and Jewish refugees. He planned the village of Niverville, establishing what might be Canada’s first grain elevator. He also managed the Manitoba Land Company, and acted as the German consul for Manitoba.

William Hespeler worked diligently to provide Manitoba with immigrant farmers after the province joined Confederation and Treaty No. 1 was signed in 1871. Since then Canada and Manitoba have had varying degrees of openness to immigrants and refugees, but certainly one of the legacies of Confederation for Manitoba is the creation of a society that largely welcomes and values the contributions of newcomers.