Posted on: Tuesday August 26, 2014

There are a number of good sites to visit if you’re interested in learning more about the HBC but one of my favourite go-to sites is produced by some good colleagues of mine at HBC Heritage Services. You can check it out here.

This website has a ton of information so I encourage you to take some time and explore it if you haven’t already. Teachers and students should head to the Learning Centre where they will find numerous features specifically created to complement curriculum across the country. The rest of the site, which is easy to navigate, is full of informative articles about HBC history. Much of the content is supplied by Joan Murray, the Corporate Historian for HBC Heritage Services, and she’s based out of the HBC’s head office in Toronto. Joan knows a lot about the company’s history and material culture, and she’s always willing to help out a newbie like me.*

I was pretty excited when Joan and her team approached me for some assistance with their website. They wanted to showcase some of the amazing artifacts from the HBC Museum Collection in the Artifact Gallery of their Learning Centre. I was able to provide them with some nice photos and captions and they took it from there, here’s a teaser but to see the full gallery click here.

Screen grab from HBC Heritage Services home screen.

Screen grab from HBC Heritage Service’s Learning Centre.

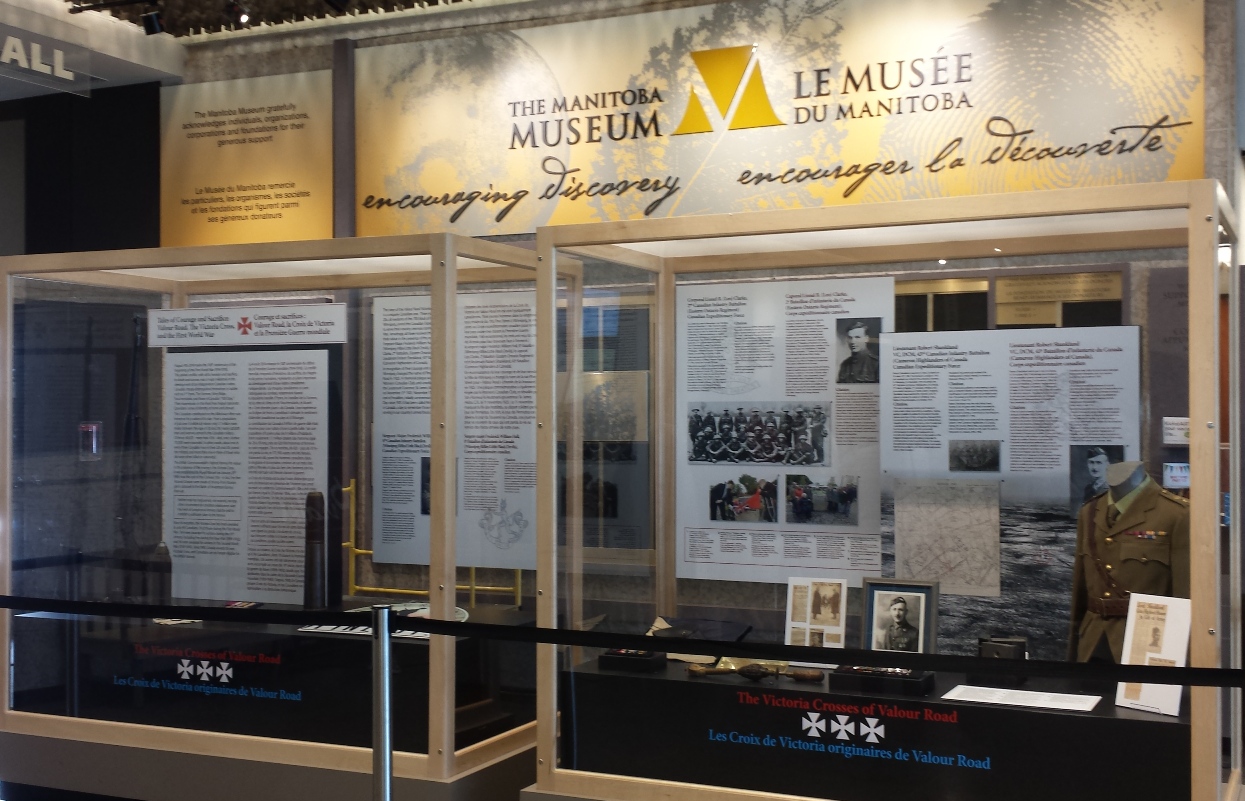

One of the artifacts from the HBC Museum Collection housed here at TMM.

I’ve been really fortunate to work with great people like Joan during my first year as a Curator, and I look forward to future collaborations with her and others. In fact, my next two blog posts will be about collaborations with some other fantastic institutions. Stay tuned!

* I can still play the “new” card until I hit my official one-year anniversary with TMM (September 3rd!).