Posted on: Friday January 16, 2015

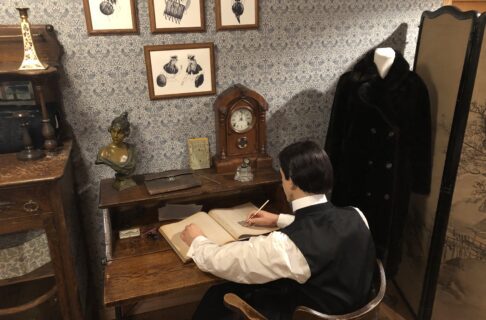

The Manitoba Museum is planning an exhibit called “Nice Women Don’t Want the Vote”, opening in November, 2015, commemorating the Suffragist movement in Manitoba. The exhibit will also discuss some of the ways Manitoba and Canada have struggled to provide full voting rights for all its citizens.

History is never neat and tidy, and the history of the franchise (the right to vote) in Canada is about as messy as it comes. While 1916 was a big year for voting rights, Manitoba being the first province in the country to extend the right to vote to women, we do need to remember that this was only for some women.

In Manitoba, First Nations people living on reserves and receiving an annuity from the Crown were barred from voting until the mid-20th Century. Indeed, from Confederation on, both provincial and federal voting rights for First Nations were curtailed and cut off until, by 1919, no First Nations people living on reserves were allowed to vote in federal elections. In Manitoba, the Treaty population, both men and women, were only enfranchised in 1952, a full 36 years after the vote was extended to women from newcomer populations. In 1960 the House of Commons gave First Nations the right to vote for the first time federally, with no restrictions. For many years before this, First Nations people could only attain the right to vote if they gave up their rights ensured under Treaty.

The women who fought for the vote in 1916 seem to have completely ignored the issue of voting restrictions on First Nations men and women. Through our research we have come across no references to the issue, and the silence is telling. Canada was dominated by a British population who considered themselves an extension of the British Empire. The leaders of the women’s suffrage movement were largely of this background, as were most of the followers of the movement. Voting rights for First Nations were just not on the radar.

Likewise, some of the women involved in the Suffragist movement debated granting the vote to immigrant women (those not born in the United Kingdom). It must be noted that this was occurring during the height of the First World War, when anti-foreign sentiment was running hot, and any ideology that was perceived as a threat to the Empire (like giving immigrants the vote) had little chance of passing through the corridors of power. Mennonites and Doukhobors, for example, had their right to vote rescinded in 1917-18 because of their refusal of military service.

Enfranchisement, the right to vote in a democratic society, has only in the last 50 years been seen as a general right of all adults in Canada. Before this, it was a slow crawl to full suffrage. In 1867, only 11% of the population could vote, and these were almost exclusively white males that owned a certain amount of property or cash. Even before this, Catholics, non-British immigrants, Jacobites (!), Jews and First Nations were excluded in one way or another from voting in different parts of Canada. The vote was also denied to Asians in British Columbia until 1948, and to women in Quebec until 1940. The geographical isolation of some groups in the north until the second half of the 20th century also hindered them from exercising their right to vote.

As we work to create this exhibit, we hope that Manitobans continue to contact us with artefacts, stories and opinions about the right to vote for women in Manitoban history.